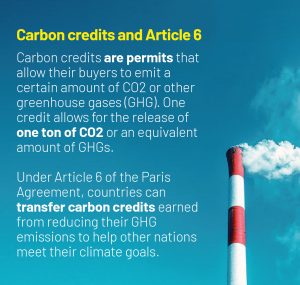

A deal at the COP29 climate summit to speed up global participation in carbon markets promises to move billions of dollars in emissions-reduction projects, especially for poorer countries.

But to achieve that, carbon trading will first need to win over countries and communities that have grown wary of scandals and disappointments shadowing the credits market.

Carbon trading is seen as one way for richer countries to meet their emission reduction targets at the same time as helping poorer countries move to greener energy and to improve their resilience against climate change.

Also on AF: COP29: What Will Donald Trump Mean For Global Carbon Markets?

And while the prospect of selling credits does offer a boost to cash-strapped governments, many climate activists and officials remain wary – or outright opposed.

Environmental group Greenpeace has called offsets a “smokescreen,” while the WWF opposes their use. Some local communities are also against using them.

Eriel Deranger, executive director of campaign group Indigenous Climate Action, and a member of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation in northern Alberta, Canada, said carbon credits distracted from calls for more public funds for climate action, and for companies to simply cut their own emissions.

“It’s going to do substantively nothing to actually reduce our emissions,” she said.

The European Union, for those reasons, has ruled out using credits to meet its domestic climate goals. That’s even as the bloc runs the world’s most valuable carbon market, the EU emissions trading systems (ETS).

The market was worth around 770 billion euros ($812 billion) last year, up 2% from the previous year and representing 87% of the global total.

But the EU market — known as a compliance market — is just one way the world trades carbon credits.

Private firms and individuals often participate in much smaller voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) to manage their emissions footprint.

And VCMs have over the past years remained fraught with concerns like greenwashing. That could mean companies buying cheap credits that don’t actually cut the emissions they promise, or scams where a company offers credits from an emissions reduction facility that in reality does not exist.

Can a UN-backed market be the answer?

A UN-backed global market for creating and trading carbon credits has been discussed for at least 10 years. In fact, emissions trading has been on the agency’s to-do list since at least 1997, with the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol.

But it took the deal early last week for some nations to finally agree on some quality standards for carbon credits. Many more points still need to be hammered out.

They include what a global registry to track trades and label carbon credits would look like, and what information projects will need to disclose.

If a deal can be reached this week in Baku, Azerbaijan, “the main impact would be a confidence boost”, said Andrea Bonzanni, international policy director at the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA).

“It would provide both countries and the private sector with the signal that there is consensus on the rules of the game. And that would mean that companies would invest with more confidence,” he added.

IETA has said a UN-backed market could be worth $250 billion a year by 2030, and count towards offsetting an extra 5 billion metric tons of carbon emissions annually.

Private sector buyers of those credits could include airlines, which are looking to scale up their purchases under a UN-backed plan launching in 2027.

Buyers could also include companies looking to burnish their green credentials with customers and investors.

Meanwhile, for countries which opt to sell credits on the UN-backed market, African Development Bank chief executive Akinwumi Adesina warned against doing so too quickly or too cheaply, to avoid being “short changed”.

Uganda’s energy minister, Ruth Nankabirwa, said her country was seeking to attract investment in clean cookstove projects, but had yet to use credits.

“It isn’t clear how one can benefit, how the auditing is done of carbon credits,” she said.

Nkiruka Maduekwe, director general of Nigeria’s national council on climate change, agreed, describing high integrity carbon credits as “the key”.

So why has progress been so slow?

Governments including Bolivia, Singapore and Switzerland have struck dozens of agreements already to do carbon credit trades under the impending UN rules, backing investments in clean cookstoves and solar power.

Others are expected to join in as they face pressure to show progress towards their national emission-reduction targets.

But governments are still struggling to agree on the rules of the registry.

The EU wants a registry that can issue and manage credit trades, to help poorer countries access the market, people familiar with the negotiations told Reuters.

The United States, however, is advocating for a registry that only tracks credit trading, arguing that empowering it to execute trades could risk giving a UN seal of approval to credits with weak environmental credentials, the sources said.

Even if a deal is reached between countries, companies may still need government incentives to buy in, given their pledges so far have been voluntary and boards are concerned about reputational risk, said Sheri Hickok, chief executive at carbon project developer Climate Impact Partners.

Flooring company Interface and Australian telcom giant Telstra, previously big buyers of credits, both told Reuters a UN deal would not change their decisions to exit the carbon markets, as they focus on cutting their emissions directly.

- Reuters with additional editing and inputs from Vishakha Saxena

Also read:

G20 Countries Reach ‘Fragile Consensus’ on Climate Finance

Germany Rejects ‘Fake’ Chinese Carbon Credits Used by Oil Firms

‘We Are on a Road to Ruin’: COP29 Kicks Off Amid Trump Worry

Fossil Fuels Set to Drive Global Emissions to a Record, Yet Again

Scientists Say 2024 ‘Virtually Certain’ to be Hottest on Record

Floods or Drought: Climate Change Worsens Global Water Woes

Asian Economies at Risk From Inaction on Climate Change: ADB

Climate Change Has Cost China $32 Billion in Just One Quarter

Emissions of World’s Super Rich ‘Drive Economic Losses, Deaths’

Energy Emissions Set to Peak But ‘Not in Time’ For Climate Goals

Scientists Fear Nature’s Carbon Sinks Are Failing – Guardian

Could Melting Glaciers Trigger Volcanic Eruptions? – Reuters