(ATF) The only country that is comparable in size to China is India. With populations of 1.40 billion and 1.33 billion people, respectively, they are home to an overall 36% of the world’s population. From May until the recent truce engineered in Moscow, the China-India border dispute has threatened to fracture efforts to foster bilateral ties between the two economies, such as India’s banning of Chinese apps in response to the conflict.

The tension over the summer revealed not just the growing and asymmetric role of China in India’s trade and investment, but also India’s unease in relation to China’s ascent in global economic and geopolitical influence, as the two started from a relatively similar position just decades ago. India has a large trade deficit with China, primarily in manufactured goods such as chemical products, machinery and electronics. Some 15% of India’s imports are from China, while only 5% of India’s exports go to China in primary commodities and chemical products. While that may mean China has more to lose should trade relations falter, India also finds it hard to shift away from certain Chinese products such as machinery and electronics given the large share of import dependency on China.

On top of rising export prowess to India, China has also deployed more capital to India in recent years, whether that be directly or indirectly through financial centres such as Singapore. The increase of investment and trade reflect China’s search for growing markets to export its production surplus, as well as its digital footprint. Additionally, India’s ambition to improve its infrastructure is also attractive for Chinese firms that want to leverage their infrastructure building capacity. The recent curb of Chinese firms points the shutdown of a potential lucrative market.

The conflict may show China having more to lose, as India represents a lucrative market for the future, but it also highlights India’s underperformance in past decades as China races ahead to boost income and build capacity, not just domestically but increasingly globally, as it manages to vertically integrate its supply chain.

India has the world’s second largest population and will have the largest working age population by 2050, as its fertility rates remain higher than China. Yet despite this, its current working age population are either not participating in the labor force or in informal sectors and formal employment remains small. Due to the lack of emphasis on attracting manufacturing foreign investment, India has not been able to capitalise on its massive labor force in the same way that China, or even the rest of Asia, has.

Thus, the conflict points to two contradictions in the India-China relations, as well as the Indian economy itself: India has immense potential, and one that investors, including China, perpetually place bets on. But the economy currently underperforms significantly relative to China as well as its own capacity. In 1993, both India and China were equally disadvantaged, with GDP standing at US$377 per capita. Fast forward to 2019, India’s GDP per capita had risen to $2,104, while China had fast-tracked to $10,261.

India’s economic underperformance stems from an inward economic policy that favours protection of domestic firms and workers over participating more in the global value chain. Within Asia, despite having a young demographic profile and relatively cheap labor, India has the lowest share of GDP in merchandise export exposure, with gross exports peaking in $337 billion in 2013. India’s participation in the global value chain has also weakened since 2013.

Stuck in slow gear

Reforms such as “Make in India” are geared towards changing this trajectory, but so far it primarily attracts services and information & communications technology – not enough is in manufacturing FDI. With such a weak labor market and huge demographic boom in the future, absorbing manufacturing firms looking to diversify from China, is a no brainer. That said, performance has remained weak and more urgency is needed. For example, in 2019 India exported a comparable amount in manufacturing goods to Vietnam, a country much smaller in size. It does not help that Modi’s pledge to improve infrastructure is held back by limited public funding and a banking sector saddled with bad loans and dominated by state-owned banks. In fact, the quality of India’s infrastructure has seen little improvement over the past five years. And infrastructure spending has been stuck in low gear since 2012.

These challenges are well understood within the academic and political circles of India and have been sources of how to address the ills of India’s under-performance despite great demographic potential. India announced steep corporate tax cuts in September last year, which answered investors’ calls for bolder reforms by slashing the corporate nominal income tax rate and targeting manufacturing investment.

Clearly, with the tax incentives, the government is tackling one of the key challenges of the country’s investment landscape, which will undoubtedly be helpful. That said, there is still more room to unleash India’s animal spirit. For one, India’s economy is rather inwardly driven as indicative by its high import barriers through tariffs restrictiveness relative to the rest of the world. For FDI, too, there is more that can be liberalised. Beyond this, one of the key challenges to investment and development in India is restrictive land and labor laws.

While the government has chosen 10 sectors – electrical, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, electronics, heavy engineering, solar equipment, food processing, chemicals and textiles – to promote manufacturing, it still has a way to go to show a more welcome face to global firms. If India can provide firms with a one-stop shop of getting land with power, water and road access, in addition to loosening labour laws, that can spur new investments.

There are signs of a more proactive policy. Recently, some states started to unshackle its land and labour policies to attract investment. Currently, investors that want to set up a factory in India need to acquire land on their own. The cumbersome process can delay a big project. As it stands, while progress is being made, the fact remains that India is taking a state-by-state approach to FDI attraction and a more coordinated effort is needed.

The future can belong to India, should it choose to capture the opportunity. By 2050, India’s population is expected to rise to 1.64 billion, while China’s is set to remain at 1.40 billion. India’s more youthful future means its market is among the most lucrative in the world, evidenced by a rise in investment by US tech firms during Covid-19, despite the economy recording the worst GDP in Asia. Debt-wise, private sector leverage in the system remains low. If anything, India has deleveraged in recent years in comparison to China’s rising debt pile. India is not in the crossfire of US-China strategic competition – in fact stands to gain from it, should it position itself to attract investment.

If the China-India conflict has a silver lining, then it is a reminder that India has the choice of whether it wants to capture or miss this window of possible growth.

ALSO SEE: Southeast Asia underperformance to reverse

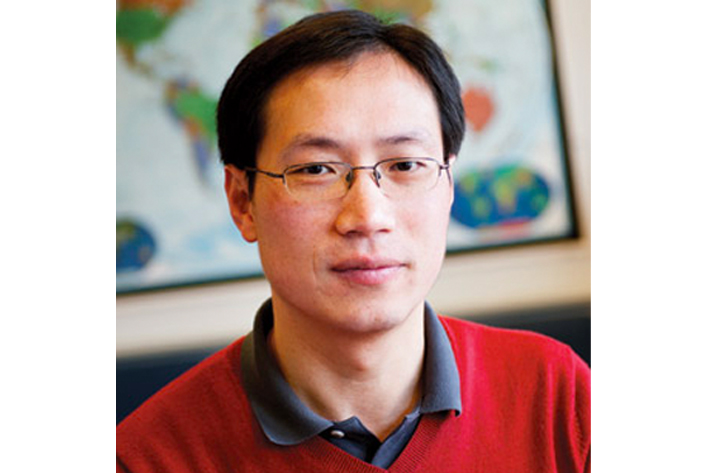

# Trinh Nguyen is Senior Economist covering Emerging Asia at Natixis in Hong Kong. Trinh is an award-winning economist with expertise and insights on the economic trends and the forces shaping them in the Emerging Asia region. Prior to Natixis, she was an Asia economist at HSBC and a research consultant at the World Bank. She holds a Master of Arts in International Affairs and International Economics with a focus on Southeast Asia from Johns Hopkins University.