(ATF) China’s bond market is now the world’s second-largest after the US and while the impressive growth of China’s offshore bond market is well-noted, it is the spectacular rise of its onshore bond market that has our attention.

Onshore corporate bonds have recorded the fastest growth; it is here we see attractive opportunities for investors looking for diversification and yield.

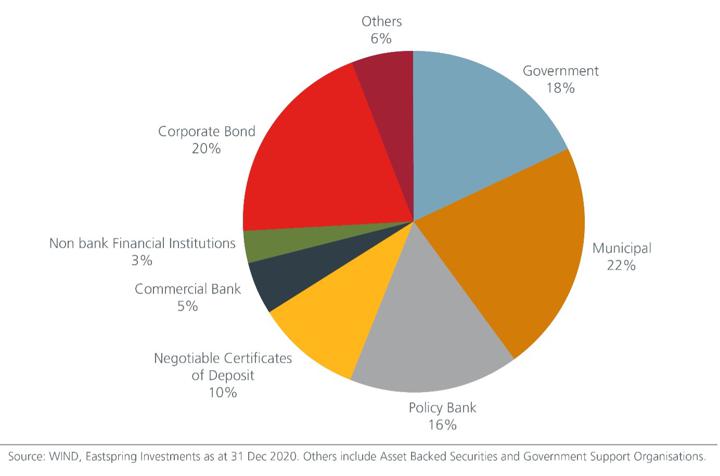

The size of the bond market has grown from just 20,669.4 billion yuan (USD 3.1 trillion) in 2010 to more than 114,310.5 billion as of December 2020 – more than five times larger than a decade ago. Municipal and corporate bonds are the two largest segments, accounting for 22% and 20% of the market, followed by central government bonds at 18% and policy bank bonds at 16%. See Figure 1.

Out of this total, the total size of the onshore credit bond market is approximately 42.8 trillion yuan, of which 22.9 trillion yuan are issued by non-financial corporates and 19.9 trillion yuan by financial institutions. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) and local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) represent the dominant issuers this segment.

Figure 1: China’s bond market composition

Reforms boost onshore bond market growth

China’s onshore corporate bond market was relatively undeveloped until 2010 as Chinese corporates traditionally relied on bank borrowings as the main funding channel. Since then, as part of the financial market reform and opening-up, Chinese regulators have issued various policies to reduce the economy’s dependence on the banking system.

In 2015, the China Securities Regulatory Commission has loosened requirements to allow non-listed corporates to issue bonds, as opposed to previous rule that only listed companies could be participants of the bond market. This has led to a surge in corporate bond issuance and a structural shift away from bank financing. By the end of 2020, the ratio of outstanding corporate bonds to loans was at 13.3%, compared with 6.8% at the end of 2010.

Furthermore, stringent regulations on shadow banking financing have also channelled part of corporates’ financing needs to the bond market. As a result, the corporate bond sector has been the fastest growing segment of the onshore credit market over the past years.

Foreign participation in onshore corporate bonds remains limited

There has been a notable pick-up in the pace of foreign inflows over the past two years; foreign holdings of China domestic bonds have risen from 765 billion yuan at the end of September 2015 to 3,012 billion yuan at the end of September 20201. But the increase in foreign holdings is mostly in Treasury and Policy Bank bonds.

The participation in corporate bonds has remained limited due to various challenges. To begin with, the language barrier posed difficulties to conduct fundamental credit analysis, especially during the pandemic. Moreover, inconsistent rating systems and lack of a meaningful presence of global rating agencies in China have made it tough to compare against the standards used in developed markets.

Currently, the nine domestic credit rating agencies and onshore ratings are generally skewed towards the high end of the credit spectrum, resulting in a lack of credit differentiation. 89.3% of credit bonds are rated AA and above, of which 65.3% carry ratings of AAA. That said, it is noteworthy that the global rating agencies are entering this market. One of them has received a rating licence in 2020 and launched their first onshore ratings.

Rising corporate default rates since 2016 and uncertainties in the post-default process have also stymied foreign interest. Furthermore, the poor liquidity of corporate bonds (albeit improving) compared to Chinese government and policy bank bonds is another major challenge. This is reflected by the generally lower market turnover and wider bid-ask spreads.

Trading of corporate bonds in the secondary market typically involves bonds issued by large central SOEs and provincial-level local SOE/LGFVs, while trading of bonds issued by private companies are less common as investors tend to hold them to maturity.

Are concerns over rising onshore defaults justified?

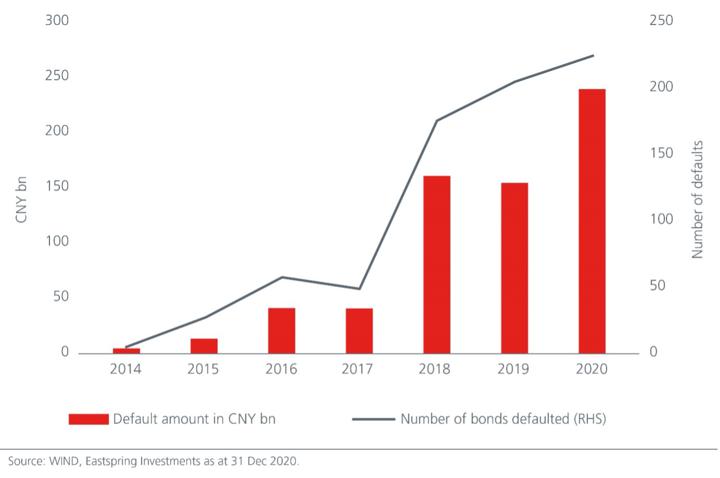

Of all the challenges, the most pertinent is the onshore default incidents in recent years. The first domestic corporate bond default occurred in 2014. Since then, the default rate has been on a rising trend, with 184 new defaults in 2019 and 224 in 2020, resulting in a default rate of 0.75% and 1.04% respectively. See Fig 2. However, we see this as part of the inevitable process towards a market-oriented bond market, like that experienced by the developed capital markets years back. A bond market that allows defaults of distressed issuers reiterates the need for active management with local expertise and credit research capability.

We expect the corporate default rate to maintain at a reasonable level compared to the global markets, with a combination of policy support, steady economic growth, and a more favourable investor structure.

Figure 2: Defaults on the China onshore market

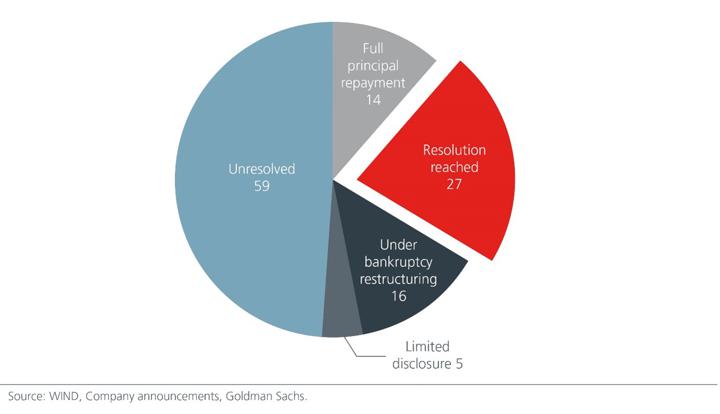

Uncertainties on default resolution is another concern for investors, in terms of legal enforcement, timeline, etc., given the short default history. Figure 3 offers some perspective on the resolution status of the 121 cases of onshore bond defaults since 2014.

Figure 3: Number of onshore bond defaults by resolution status (2014 to November 2020)

Why we are positive on the onshore corporate bond market

The main incentive for investing in China’s corporate bond markets is the strong economic backdrop. While China’s economic growth has slowed, it remains on a strong and healthy upward trajectory in the next 5-10 years. As one of the few major economies that implemented normal monetary policy, China stayed away from using a deluge of stimulus policies. As a result, China has maintained positive interest rates and an upward yield curve, which are conducive towards sustainable economic and social development. In the long run, this helps to provide positive incentives for economic entities and maintain global competitiveness of yuan-denominated assets.

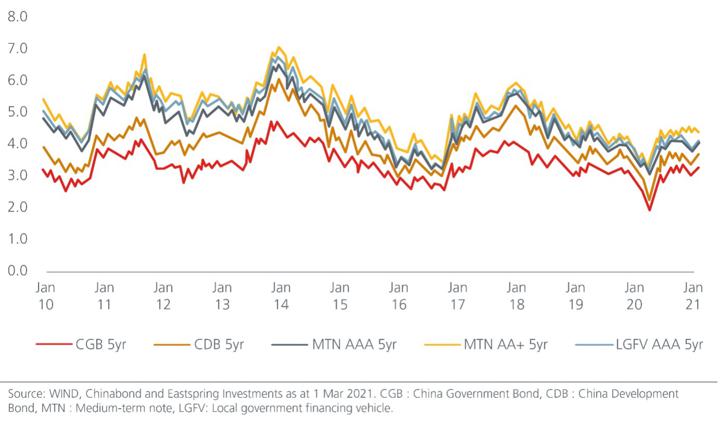

China onshore bonds also offer good relative value over their offshore counterparties. The China Bond Corporate Bond AAA Index (five-year) had a yield to maturity of 3.8% at the end of February, much higher than the 2.6% yield of offshore investment-grade bonds. The gap has widened significantly since the second quarter of 2020, when the Chinese government began to tighten onshore monetary conditions. For SOEs with international ratings of A- and above, the gap between their yuan bonds and US dollar bonds can be as wide as 200bp, without factoring in the cost of hedging and foreign exchange differences, making high-quality SOE bonds attractive for investors looking for yield enhancement. See Figure 4.

As the effect of policy normalisation fades, the yield premiums on onshore bonds may eventually fall closer to historical levels, which means better returns for onshore bond investors.

Figure 4: China onshore bond yields (%)

Investors with credit selection capabilities will benefit

Inevitably, the string of defaults, which include highly rated entities, have challenged investors’ assumption of an “implicit guarantee” that Chinese authorities would save those that run into trouble. While these credit headlines have negatively affected market sentiment, certain insolvencies and defaults are part of a healthy, functioning market if a wider contagion is contained. The recent wave of SOE bond defaults also reflects the authorities’ efforts to clean up “zombie enterprises” as part of China’s supply-side reforms with structural deleveraging remaining the key policy direction. In fact, the rising defaults show the regulators’ willingness to develop a mature financial market.

The recent rising onshore defaults and tightening onshore liquidity in China have triggered bouts of volatility. This trend has brought back investors’ attention to fundamental analysis and credit selection and we see these as opportunities for long-term investors with credit selection capabilities. Increasing credit differentiation has started to be reflected in bond prices.

It is worth noting this is not the first time that onshore defaults have sparked concerns and will likely not be the last. Ultimately, the Chinese government has the political will and policymaking capacity to steer the market back into calmer waters. Previous experience has shown its ability to contain systemic risk and maintain overall financial stability.