In November 2008, in the midst of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09, Rahm Emanuel, the soon-to-be chief of staff to US president Barack Obama, made an infamous observation. “You never let a serious crisis go to waste,” said Emanuel, underlining how a crisis can provide “an opportunity to do things you think you could not do before.”

We have such a crisis now – the Covid-19 pandemic – and China appears to have taken Emanuel’s words to heart. As the country recovers from the initial wave of infections and its economy begins to grind into gear again, Beijing is attempting to use the opportunity to demonstrate its global leadership, and favorably compare its political system to the West’s.

The diplomatic foray by China is likely having a similar effect to that felt during the financial crisis – a weakening of the moral leadership of the West and the gradual tectonic shift in the global order as Beijing recasts its role.

China’s strategy is twofold. First is to shift the narrative around the coronavirus that causes Covid-19, away from culpability. In doing so, Chinese spokesmen are both investing in conspiracy theories that cast doubt on the virus’ provenance and highlighting China’s successful record of suppressing the spread of Covid-19 at home.

Bumbling, mendacious

The latter allows a recasting of Beijing’s role, and particularly that of the Communist Party of China, away from the bumbling, mendacious initial response that involved suppressing statistics on the virus, preventing the publication of information, and failing to react with any alacrity to the growing health crisis. Instead, the CPC is to be viewed as a competent and effective body, one that through its authoritarian and collectivist political system was able to marshal its population in ways that Western democracies have struggled to do.

Second, Beijing is framing its role in the pandemic as a savior rather than as a cause. China has sent planeloads of equipment and/or medical personnel to countries as diverse as Italy, France, Serbia, Cambodia, Iran and Iraq. Beijing also supplied thousands of test kits to the African Union to be distributed among its member states, although this donation was massively overshadowed by the arrival in Addis Ababa of a planeload of equipment supplied by Jack Ma, the billionaire co-founder of Alibaba. Ma vowed to deliver 20,000 test kits, 100,000 face masks and 1,000 protective suits to each of the 54 African states.

China’s philanthropy is of course welcome in its own right, but it has an ancillary benefit for Beijing: to bolster its soft power and influence globally. It is notable that China’s offers of support have largely been to countries or regions that are already allies (Iran, Cambodia), are less developed (Africa) or are weaker states in the developed world that have previously been open to greater Chinese influence (Italy, for instance, was the first developed country officially to adopt membership in the Belt and Road Initiative).

Beijing is able to cast itself in this savior role because it claims to have already managed the spread of the coronavirus; it is home to many of the world’s factories that manufacture relevant medical equipment (and for which there is now less of a domestic need); and because there is currently no competitor for a global leader in the fight against Covid-19.

Alliances

Historically, the US would have been the state best positioned to marshal a response to a global crisis, using its well-developed system of alliances and vast resources to corral and coax other countries to act in unison. Currently, this leadership role is hampered by its need to focus on its own viral response.

But it is not just circumstance that is creating a vacuum of leadership in the West. The administration of US President Donald Trump seems deeply averse to the idea of the compromises necessary to bring together a coalition of states – on March 25, the Group of Seven, arguably comprising the states most closely aligned with the US, was unable to issue a joint statement on the pandemic because the US insisted on branding Covid-19 as the “Wuhan virus.”

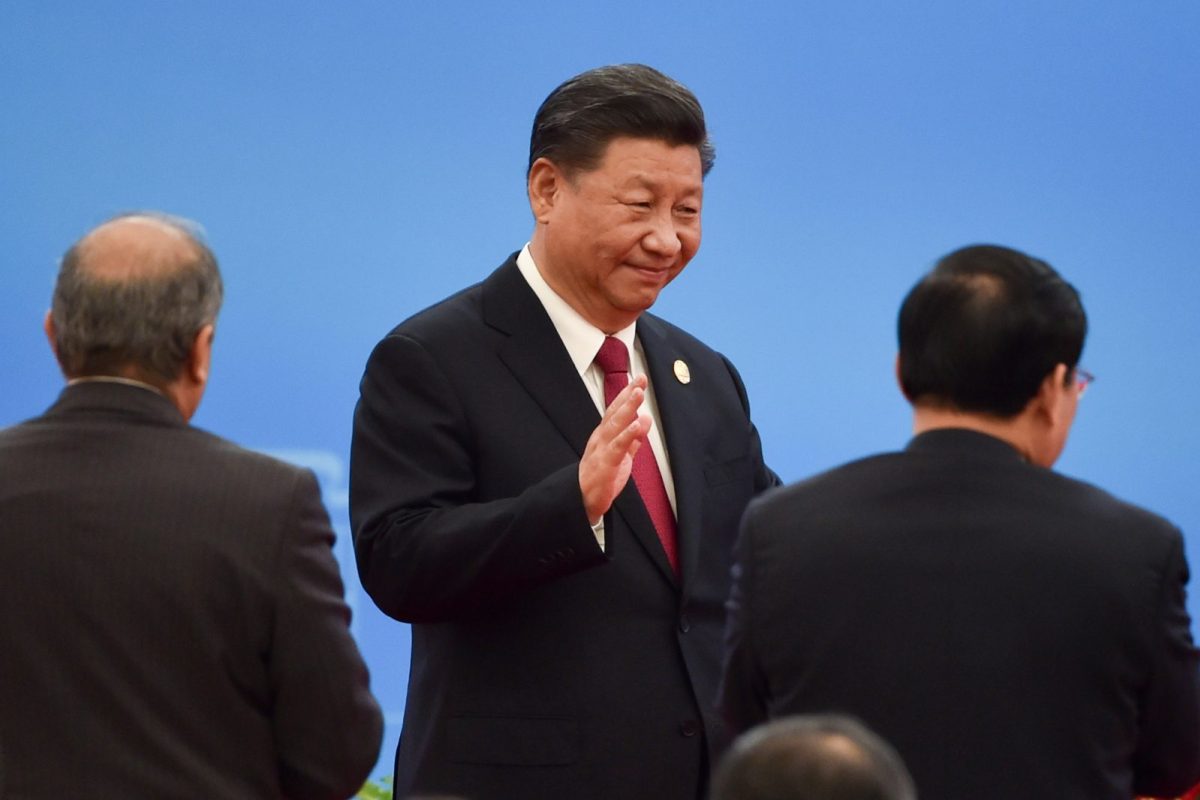

It was notable, then, that Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, desperate to stem the exponential growth of infections in his own country, chose to take a call not from the US president first, but from the Chinese president, Xi Jinping. Spain – a NATO country that hosts the United States’ largest European naval base – turned to Beijing before Washington. This could be explained by China’s greater capacity to export equipment and offer support, but it is still a remarkable shift in international affairs that would have been unthinkable 20, 10, or maybe even five years ago.

The Great Financial Crisis led to a crisis of confidence in the West – the very capitalist democratic system that had been lauded as the reason for winning the Cold War was now causing untold damage to those same countries. China, in response, utilized the occasion to suggest that its more statist economy and authoritarian political system allowed for rapid and effective responses to such crises.

The same dynamic is happening now, and its effects are likely to underline and catalyze the gradual shift in international relations that has been under way for 30 years, as China aims to extend its soft power and influence in the US-led order.

This article was provided by Syndication Bureau, which holds copyright.