As events related to the coronavirus pandemic and the government’s response unfold, it is hard to separate financial from real economic effects. With a large part of the nation’s businesses shut down and St Louis Federal Reserve Bank President James Bullard warning that the unemployment rate may reach 30% in the second quarter, earnings forecasts are meaningless. Until there is clarity from Washington about the size, content, and timing of economic support, markets will shun risk assets.

Nonetheless, the American financial system has identifiable vulnerabilities which were brought to the fore by the coronavirus pandemic and which will condition the economic outcome over the next 12 to 24 months.

Two dangerous deficits

The cure for the last crisis is often the cause of the next. The public debt of the US government rose to $23 trillion today from $10 trillion just before the world financial crisis of 2008. That does not include unfunded liabilities of Social Security and Medicare, which have been estimated at up to $100 trillion.

The deficit is likely to rise by several trillion dollars more as the government rushes to provide support for consumers and businesses stricken by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. The federal government probably will spend an additional $2 trillion during 2020 for emergency economic support and lose $1 trillion in revenue. The deficit ran at an annual rate of more than $1 trillion before the crisis, so the total deficit may come out at $4 trillion, or roughly 20% of GDP.

In addition, the Federal Reserve will expand its balance sheet by perhaps a trillion dollars to provide emergency liquidity to domestic and overseas markets, including purchases of municipal bonds for the first time.

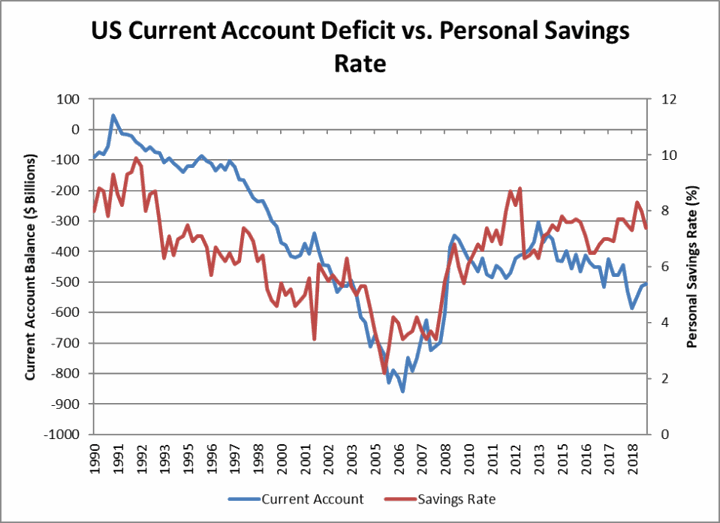

The late economist Herb Stein famously said that what can’t go on forever, won’t. Two imbalances couldn’t go on forever, and now won’t. The first is America’s budget deficit. The second is America’s current account deficit caused by its low savings rate. Americans borrow, spend, and consume, while Asians and Europeans save and lend. Figure 1 below shows that the collapse of the personal savings rate to nearly zero at the height of the home price boom of the mid-2000s coincided with the largest US current account deficits in history.

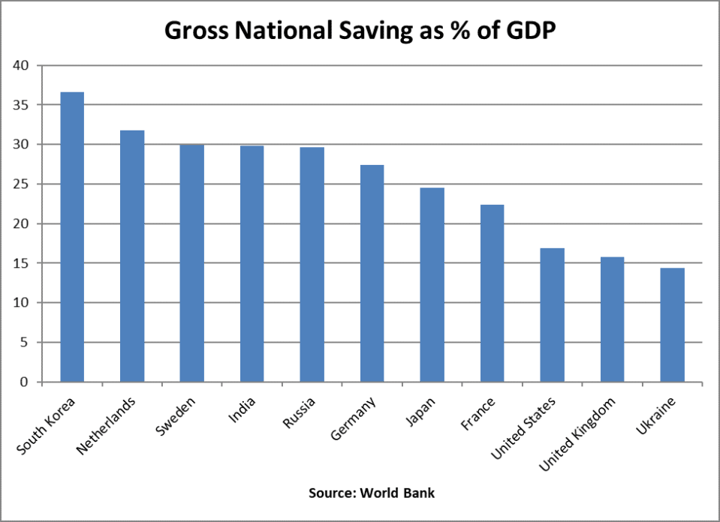

A more comprehensive measure, gross national saving (including business and government as well as personal savings) shows that the United States saves about half as much as South Korea or Sweden relative to GDP (Figure 2).

Deficits don’t matter as long as it is easy to fund them. For decades the United States has been the preferred destination for the world’s savings. US Treasury securities offered positive real yields while European and Japanese yields went negative, as the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan took extreme monetary measures to attempt to revive stagnant economies.

The first cracks in the dam began to show during the present crisis. The credit of the United States is at risk for the first time since the Civil War, although a crisis of confidence in the US dollar and US government securities is far from upon us. We have time to adjust, but not unlimited time.

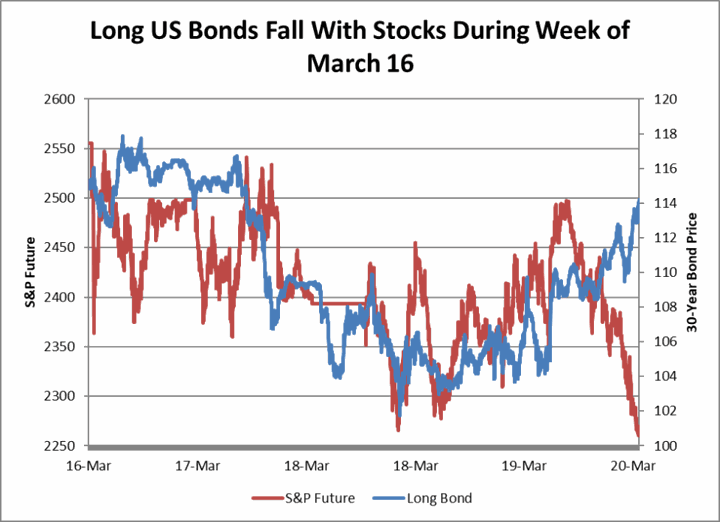

The warning signs appeared during the week of March 16. For the first time in its history, the Federal Reserve stepped into the market to buy US Treasury securities because market illiquidity forced investors to sell them. Treasury securities have been the ultimate shelter in a storm. Their prices soared during the 2008 financial crisis. Starting on March 17, Treasury prices fell along with the stock market, until the Federal Reserve pledged to buy an additional half-trillion dollars of them, in addition to the $4.3 trillion of other assets on its balance sheets. Remarkably, government bond prices fell sharply after the Federal Reserve cut its overnight lending rate to zero, hard upon an earlier cut of half a percentage point (Figure 3). That is the opposite of what is supposed to happen: bond prices are supposed to rise when stock prices fall, especially when the Federal Reserve cuts its own overnight rate.

The Federal Reserve’s weekend rate cut and quantitative-easing announcement failed to reverse a global seize-up in the financial system. Stock markets plunged because the flow of credit to businesses and households is at risk. The Federal Reserve and other central banks can buy all the assets they want and provide all the financing they want to private banks, but they can’t force private lenders to stick their heads above the parapet when the prudent thing to do is to hit the dirt.

The purely financial side of the crisis centered on the balance sheets of the global banking system. US current account deficits accumulated to over $11 trillion during the past 30 years. To finance them, the United States has borrowed the same amount from foreigners. If we buy widgets from Japan and don’t sell anything to Japan in return, Japan lends us the money to pay for them. The aging Japanese want retirement assets and Americans want to consume widgets, so both parties are happy with the transaction.

The trouble is that the exchange rate of the US dollar versus the Japanese yen is volatile. Japanese savers cannot afford a devaluation of their investments in the US, so they need to swap the interest payments from dollar-denominated bonds into their own currency. Japanese banks (and other foreign banks) borrow dollars from US banks to sell against their own currency to provide such hedges. For a detailed discussion of the mechanics of foreign exchange hedging, see this recent presentation by Hyong Sun Shin, the head of research at the Bank for International Settlements.

Foreign banks have borrowed about $12 trillion from US banks to finance foreign exchange hedges for holders of US securities – roughly the amount of the cumulative US current account deficit over the past 30 years. When the magnitude of the US health crisis became apparent, US bank customers drew down all the revolving credit lines they could in order to increase cash on hand. That put pressure on bank balance sheets, and US banks began to ration credit. Their overseas bank customers found the cost of renewing short-term loans from US banks prohibitive, and charged their customers exorbitant amounts to renew currency hedges on US security portfolios. Their customers, including insurers and pension funds, responded by liquidating US securities. Some of the safest assets, especially mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by US federal agencies, showed alarming price declines.

So the Federal Reserve provided dollar loans to foreign central banks via swap lines, allowing those foreign central banks to supply their own banks with dollars in order to stop the liquidation of US assets by foreign investors and restore order in US securities markets.

If this sounds like a Rube Goldberg machine, it is. The regime of floating exchange rates has spawned a $100 trillion market in foreign exchange derivatives to hedge the effect of currency fluctuations. Only a few monetary traditionalists, Steve Forbes for example, have argued for a return to monetary stability based on a fixed gold price for the dollar. The overhang of hedges is so great that it poses the threat of an avalanche in dollar securities markets.

Under the circumstances, the Trump Administration has no choice but to use the power of the federal government to borrow and spend to bridge the impact of the health crisis. In February, I urged the administration to offer an emergency fiscal stimulus before Washington was ready to consider it. If the Federal Reserve and the administration had acted earlier to ease the impact of the health crisis, their actions probably would have been more effective. Government intervention during market crises is something like a present for your spouse’s birthday: if you’re late, it will cost you a great deal more. The Federal Reserve, moreover, has no choice but to offer emergency liquidity.

Where do we go from here?

What we observed in the market movements during the past week, though, makes clear that the vulnerabilities of the US economy must be addressed. It is hard to fix your roof during a hurricane, to be sure, and long-term solutions may have to wait until the short-term crisis is past. Rahm Emanuel’s advice about not letting a good crisis go to waste applies here.

The market sent a shot over our bow to tell us that we cannot accumulate budget and trade deficits forever. We entered the crisis with full employment and a federal deficit of about 4% of GDP – an extraordinary situation. As noted, we may boost the deficit to 20% of GDP before the crisis is over. There are a number of ways in which the necessary adjustment can occur, most of them unpleasant.

One is a general reduction in entitlements for future generations as well as spending cuts for the present. Another is a higher level of savings, either on the part of households (who can save and buy government bonds) or on the part of government (which “saves” by increasing taxes on households and corporations in order to reduce “dis-saving” in the form of government deficits). Both of the above would require a significant, one-time drop in consumption, and probably a severe recession. The political consequences of any of these scenarios would be ugly.

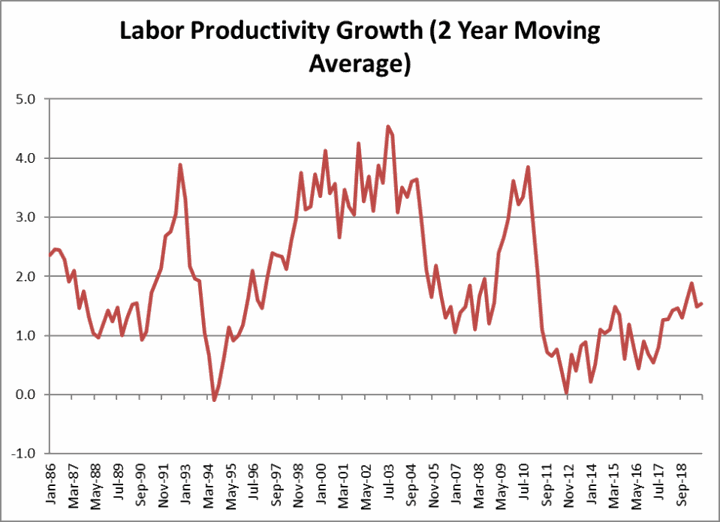

The other way in which the adjustment could occur is through a revival of productivity growth. Labor productivity growth during the past decade has languished at the low end of an historic range. Productivity growth driven by technological innovation, for example, can substitute for savings, as it gives us more output for less effort.

If the United States were to reduce its current account deficit by reviving high-tech industries, which have inherently high productivity, average productivity growth would increase, especially if new technologies were brought to bear. On the other hand, an industrial policy that centered on creating jobs in low-productivity industries would have the reverse effect. Conventional industrial policy tends to subsidize inefficient industries at the expense of the public, but government support for basic R&D on the model of the Kennedy Moonshot or the Reagan Strategic Defense Initiative has in the past put a tailwind behind productivity growth. These issues were addressed in a recent symposium sponsored by the Claremont Institute in response to proposals from Sen. Marco Rubio, to which I responded.

Addressing the causes of America’s deficit can no longer be postponed. How we address them, though, will be decisive for America’s future economic health.

This article was first published in Law & Liberty.