As Covid-19 stampedes across the planet, undermining a globalized world’s collective economy and even basic social structures, politicians and pundits around the world are seeking a villain to blame.

The patterns of finger-pointing have been predictable. In Washington, they blame Beijing. In Beijing, they blame Washington. Democrats blame Republicans. Republicans blame Democrats. And so on.

The real culprits? Mother Nature and the vast force of globalization.

Viral inevitability

The novel coronavirus is a predictable outcome of an entirely normal process of evolution – a force far more powerful than politics.

Infectious diseases have only been held in check for 100 years or so – and they have done so for reasons that are widely misunderstood. The key change factor has been dramatic improvements in sanitation across the Western world – and to a lesser extent, antibiotics, vaccines and antivirals.

But bacteria, viruses and other pathogens are also subject to the evolutionary process. They may adapt by random mutation events to survive and prosper despite human interventions. Evolution is a massively powerful force, helping all organisms adapt and survive as environments change. Mutation is the engine that powers evolution.

This is exactly how antibiotic-resistant bacteria emerged – by random mutation events in an environment characterized by overuse of antibiotics.

In recent years we have seen many dangerous bugs emerge, often originating in China.

Why China? Because of, among other things, population density, substandard sanitation compared to the West, climate and rapid economic development.

Yes – economic development.

One hundred years ago, when a disease emerged in China it took a long time to spread around the globe. But with the rapid economic development of China and frequent intercontinental flights connecting China to everywhere, new pathogens can spread much more rapidly – as we are now seeing.

Natural mutation

Like all living things, viruses mutate all the time.

Occasionally these random mutations may increase viral transmissibility and/or virulence. But virulence is generally bad for any pathogen, for simple reasons. If it kills its host, then it dies as well. If there aren’t alternative hosts around which can be infected before the current host dies, the population of newly mutated lethal bugs will quickly go extinct.

When highly virulent mutations arise in sparsely populated places, the effects are localized and do not easily spread. And this happens all the time, all around the world.

Pathogenic mutation events happen all the time in Africa and other densely populated parts of the developing world as well. But for economic reasons, there is much less connectivity to the rest of the world, so diseases can more easily be geographically contained in the region.

For example, the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa exploded when it reached densely populated capital cities, but ended up remaining largely contained within the region, with a few exceptions.

As African countries develop economically, and the world becomes more and more interconnected, the potential for pandemics will inevitably become a bigger and bigger issue – because this is simply how evolution works.

As we continue to develop countermeasures, mutations will continue to happen. Sometimes these mutations will confer advantages to pathogens that allow them to circumvent our countermeasures.

Climate also plays an important role as many tropical diseases are transmitted primarily by insect vectors, and don’t therefore influence those of us living in more temperate regions. For example, the Zika virus outbreak in 2015-2016 quickly spread through Latin America, but was largely limited to the range of its mosquito vector.

China’s centrality

China, however, has a similar climate and geography to Europe and the US, and therefore mutated germs that emerge there have a greater potential to cause havoc for us in the West.

From there, the connectivity of the world allows them to easily and rapidly spread internationally once they reach a critical mass in the population.

And the population of China is massive. It is roughly equivalent to that of Europe, North America, Australia, Japan and Korea combined, and has a population density more than four times higher than Europe and the US – despite China’s remarkable and largely unsung success in controlling its population growth.

In large, densely populated Chinese cities – remember that even New York City would not be considered particularly large by Chinese standards – there are tons of potential alternate hosts around to infect, such that even highly virulent bugs can take root and become serious problems if they are reasonably transmissible.

So, it is unsurprising that many pandemic diseases originate there.

We shouldn’t blame China for its remarkable economic progress. However, what has become clear is that ongoing globalization is a significant factor in why China-originated bugs are starting to emerge and spread so rapidly worldwide.

What governments must do

The emergence of new pathogenic strains is inevitable. Yet the developed world invests disproportionately in studying the minuscule effects of genes on what are largely lifestyle-driven chronic diseases in the Western world. In a world of limited resources, it does so at the expense of devoting attention to the microscopic army of bugs who are our real enemy.

Governments would be wise to redirect a significant fraction of research and public health funding away from extravagant, unfocused “big-data” genomics projects like “All of Us.” A new focus – on critical infectious disease research and epidemic preparedness – would help us better prepare for the next time.

And there will be a next time, for the current levels of domination humans have over pathogens is not guaranteed to last forever.

I have often wondered whether we may outlive our great-grandchildren because we are fortunate to be alive in an era when we have successfully suppressed many infectious diseases, before they have had time for adaptive countermeasures to arise and spread.

Ultimately nature provides the balance. Overpopulation breeds disease. Connectivity helps it spread. Amid these conditions, let us hope that human ingenuity is up to the task as we fight to maintain this dominance over our microbial enemies. That fight demands both focus and funds.

Covid-19: The positives

Data suggests Covid-19 will be mild or even asymptomatic for the majority of otherwise healthy working-age individuals. I do not wish to minimize the very real health risks of Covid-19.

If you interact with old or sick people, do all you can to minimize their risk of becoming infected, while we wait for the development of effective countermeasures. For example, don’t use grandma as a cheap babysitter.

But speaking more broadly, our response to this pandemic provides an important exercise of the world’s public health systems. By taking this effort very seriously, in addition to saving lives, we will learn how to better prepare for future challenges, as dangerous pathogens will inevitably continue to emerge and spread throughout our ever-more-globalized world.

To be fair to China, they seem to have learned from past experiences, and handled this unfortunate outbreak significantly more effectively and responsibly.

But the response has been far from perfect. Both China and the West can do better.

In the meantime, we need to stop blaming each other for how we got here. We are in this together. In an interconnected globalized world, linked by travel and made wealthy by trade, we all have no choice but to work collaboratively.

Arguing about politics and searching for scapegoats is not only a waste of time and energy, it takes the focus off the key tasks facing us all: disease management, crisis management – and the future research necessary to upgrade these critical activities.

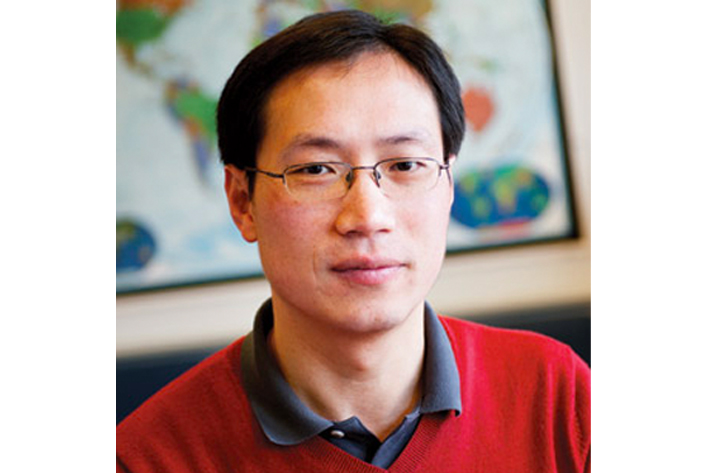

Joseph D Terwilliger is a Professor of Neurobiology at Columbia University (in the Department of Psychiatry, the Department of Genetics and Development, and in the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center), and he is also a Research Scientist in the Division of Medical Genetics at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr Terwilliger works as a statistical geneticist focused on study design and statistical inference in genetic epidemiology and evolutionary biology, working mostly with isolated human populations in the developing world.