US stocks with stable cash flows that used to trade like bonds have fallen faster than the overall market during the past few days. That’s an alarm bell for the US economy, which for the past decade has gorged on cheap leverage provided by the Federal Reserve. Investors are running away from the credit risk of seemingly safe sectors like real estate and utilities. When the safest stocks aren’t safe anymore, the world looks a lot riskier to everyone.

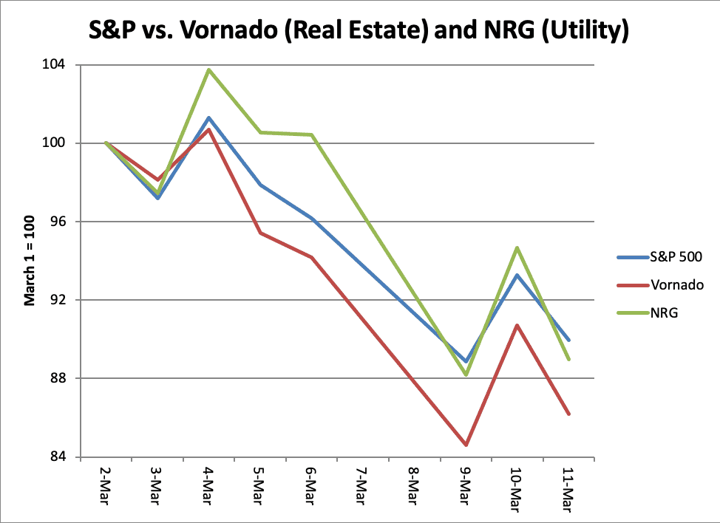

Real estate and utility shares with more economic exposure have suffered the most. Vornado, which owns office buildings in major US cities, fell more than the S&P 500 this month despite falling Treasury yields. NRG, a utility that specializes in alternative energy, also performed worse than the market. These are high-dividend stocks favored by retirees.

Southern Co, one of the largest and most stable US utilities, lost more than the S&P 500 between March 4 and the morning of March 11.

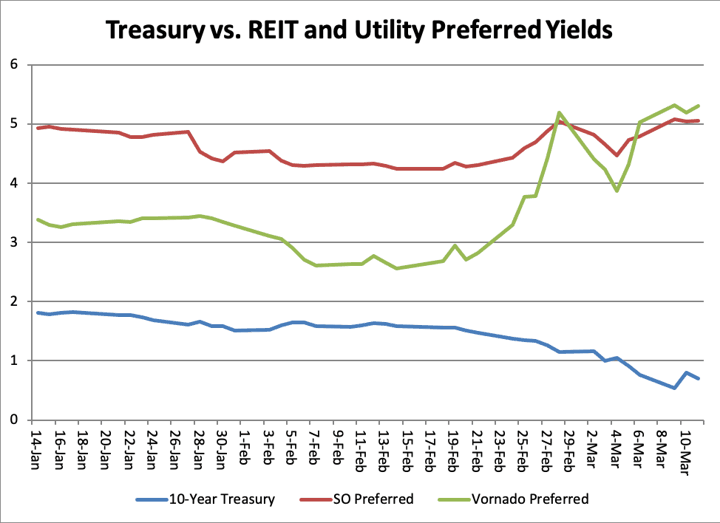

The reason for the underperformance of formerly safe stocks is observed easily in the credit market. Ten years of quantitative easing and low interest rates allowed corporate managers to lever up their balance sheets with low-cost credit. The most reliable cash flows, such as utility rates and office rents, attracted the most leverage. Now the credit markets are seizing up even for assets that attracted easy financing until the present stock market crash.

Vornado’s preferred stock (effectively a bond with no claim on recoverable assets in the event of bankruptcy) yielded barely 2.5% in mid-February, when the 10-year Treasury yielded around 1.6%. Since then the Treasury yield has collapsed to about 0.70% while Vornado’s preferred yield shot up to 5.25%. That’s an important number. The capitalization rate (the ratio of rental income to building price) in top US cities is now 2%-3%, or exactly what Vornado would pay for new preferred debt a month ago. In other words, the real estate investment trust was able to earn a minimal profit at its marginal cost of financing. At 5.25%, Vornado can’t make money.

Remarkably, Southern Co’s preferred yield rose from 4% to 5% while the Treasury yield collapsed. That’s an ultra-safe, regulated utility. But utilities operate with all the leverage they can get, and an increase in the marginal cost of credit has a direct impact on the bottom line.

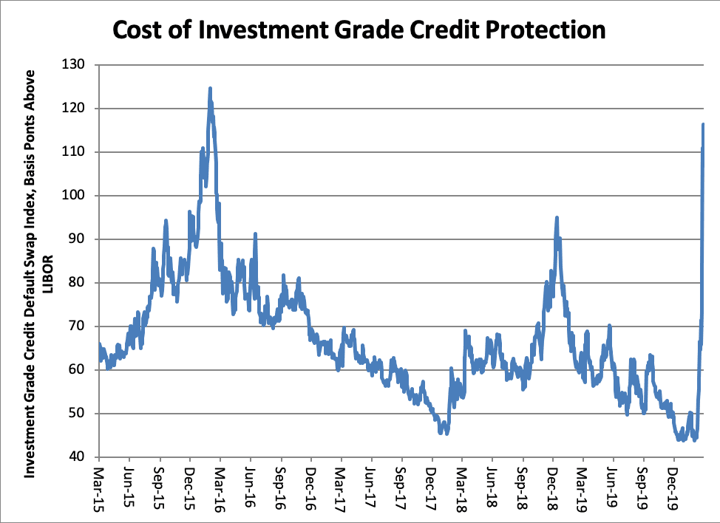

On average, the cost of investment-grade credit isn’t alarming. During the past few sessions the cost of insurance on an index of investment-grade bonds has risen to the levels last seen in early 2016, when the US economy seemed on the brink of recession.

But it isn’t the average price of credit that worries investors: It’s the prospect that a few big names will lose access to the credit market and go into a tailspin.

The market is rapidly running out of places to hide. Consumer staples names like Coca-Cola have fallen in line with the market during the past week. Heavily-geared stocks like Molson Coors (with $12 of net debt for every dollar of pre-tax earnings) have fallen much more; the brewery company is down about 20% on the week. Wal-Mart, Campbell’s Soup, and the drugstore companies have done well, the beneficiaries of panic buying and anticipated higher business due to the coronavirus.

This isn’t a panic, but is a severe test for corporate managers who have substituted leverage for underlying earnings. The bubbliest parts of the stock market include traditionally safe sectors that turn out to be debt traps.

READ MORE: Food prices continue to rise in China