(ATF) The coronavirus-triggered supply chain dislocations had many calling for a stampede out of Asia with outsourcing contracts moving closer to the consumption centers.

Rather than reversing, the trend will only intensify as manufacturers stockpile more critical parts, with supply chains proving to be more robust and manufacturers dumping the “just in time” model.

Add to that the spectre of inflation and you have a solid economic case for acceleration of outsourcing and supply chain adoption.

What a difference a year makes.

Flashback to the start of 2020 — US and European leaders wanted to steer companies away to make sure they set up domestic supply chains and cut reliance on China in what was called the great uncoupling of the world’s two biggest economies.

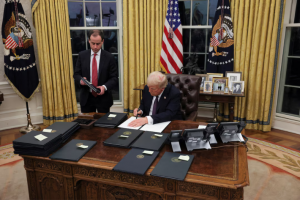

Former President Donald Trump had said “the final step in rebuilding the stockpile is to bring critical manufacturing permanently back to America” and his administration had begun crafting proposals to push American companies to move operations or key suppliers out of China by offering them tax breaks, new rules, and carefully structured subsidies.

The roadmap included the idea of a “reshoring fund” with an initial outlay of $25 billion – to encourage U.S. companies to drastically revamp their relationship with China.

The timing was uncanny, and carried with it a special appeal in an election year. Anti-China missives, pro-American job proposals were aired with an eye on the voters.

However, untangling supply chains built over five decades of economic co-operation between US and China is a daunting task. And although many manufacturers were perhaps rethinking their presence in China, very few acted upon it.

A poll conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai showed manufacturers had no intentions to move.

Conducted across more than 200 respondents that own or outsource manufacturing operations in China, 70.6% said they did not intend to shift production out of China. While 14% said they were moving some production to non-US locations, just 3.7% said they were moving some production out of China to the U.S.

This faith was later rewarded by the speedy recovery made by China’s supply chain eco system after the pandemic – a rebound acknowledged by Apple CEO Tim Cook in a recent analyst call.

In fact, with most companies in the post-COVID era looking at cost-saving and integrating processes and technology, and the fundamental argument for globalization and therefore for outsourcing will become even more relevant.

Since the early days of the pandemic, much attention has been paid to strengthening the supply chains to prevent shortages which would result in production disruptions. Curiously these trends have also accelerated on the back of growing nationalism, geo-political tensions, and protectionism.

So while protectionism and nationalism has triggered higher tariffs as countries seek to protect their own industries, there is a trend towards stepped up foreign direct investments which would mean more jobs and factories in regions like Asia.

For example, China has reported FDI of $46.38 billion in the first quarter this year, a jump of 39.9% over 2020 and 24.8% rise over 2019.

Emerging markets have also posted a higher share of global FDI – In 2020 it rose to 72% of the world aggregate, the highest on record. Both Asian giants , India and China reported a positive growth in FDI inflows at a time when the overall flow declined for the world at large.

Moves to strengthen the global supply chains that are in place will also benefit regions like Asia. For example, diversification of sources.

Countries like India, Vietnam and Indonesia are positioning themselves to tap this opportunity by enhancing manufacturing capabilities and cutting labour costs.

But a large-scale shift is easier said than done and at best only a few low-end production facilities are likely to move.

Sometimes these very nationalist policies can result in accelerated globalization.

A study by Britta Glennon, Assistant Professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, showed that multinational firms faced with visa constraints have the option to hire the labor they need at their foreign affiliates. If they were to use this option, then restrictive migration policies are unlikely to have the desired effects of increasing employment of natives, but rather have the effect of offshoring jobs.

When former US President Trump signed the Buy American and Hire American Executive Order in early 2017, foreign affiliate employment increased both in countries like India and China with large quantities of high-skilled human capital and in countries like Canada with more relaxed high-skilled immigration policies and closer geographic proximity.

The end of the pandemic itself may have its roots in globalization.

The BioNTech-Pfizer vaccine was created by a German biotech firm founded by scientists with Turkish heritage attracts investment from a Chinese conglomerate and joins hands with a US pharmaceutical behemoth helmed by a Greek chief executive.

READ MORE: