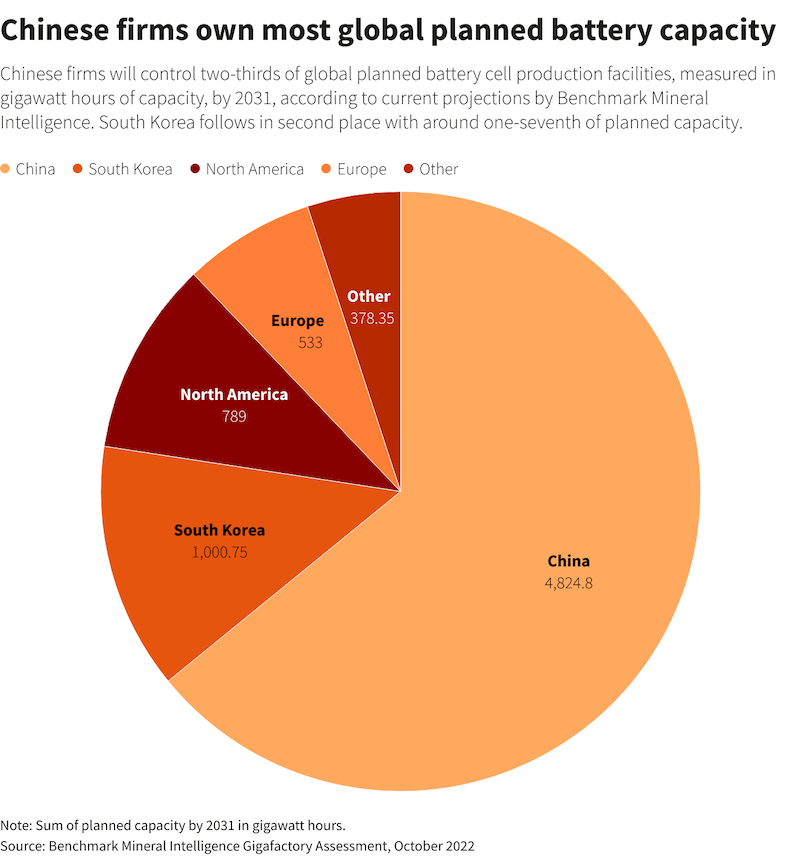

Chinese and Asian firms look set to dominate the electric vehicle battery sector in Europe, despite efforts by the European Union to kick-start a homegrown industry.

A push by European officials five years ago to build a homegrown EV battery industry has stalled because investors have yet to give startups sufficient funds to challenge the Asian companies that lead the market.

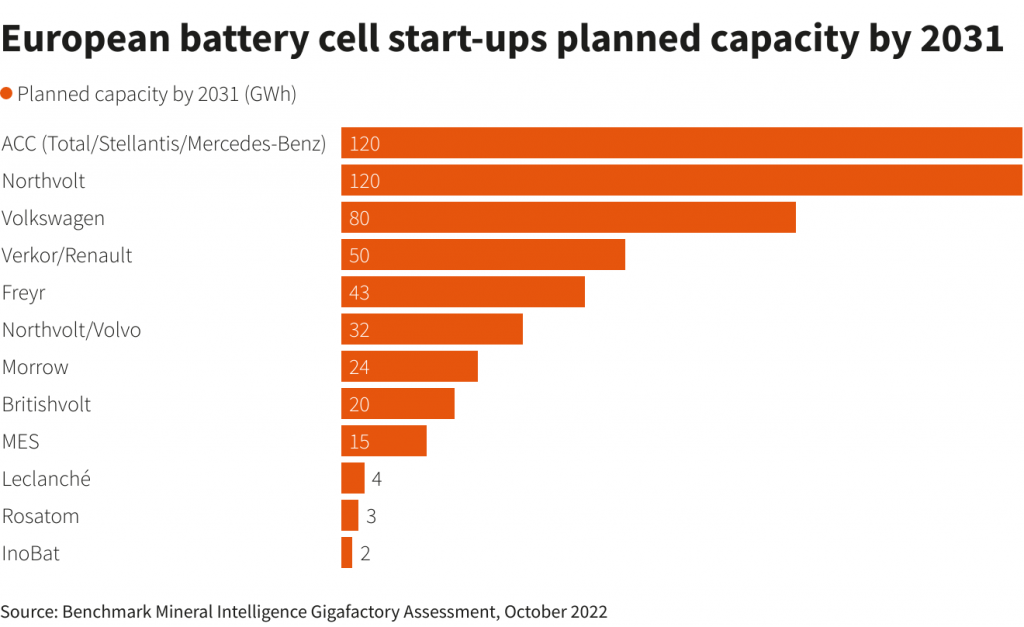

With the exception of Sweden’s Northvolt, startups hoping to build “giga-factories” to compete with the Asian behemoths are going for smaller plants, with the aim of attracting more investment further down the line.

The European Union launched the European Battery Alliance in 2017 to kick-start local production, with a goal of getting companies in the region to provide 90% of the batteries needed by 2030 to power the energy transition on the continent.

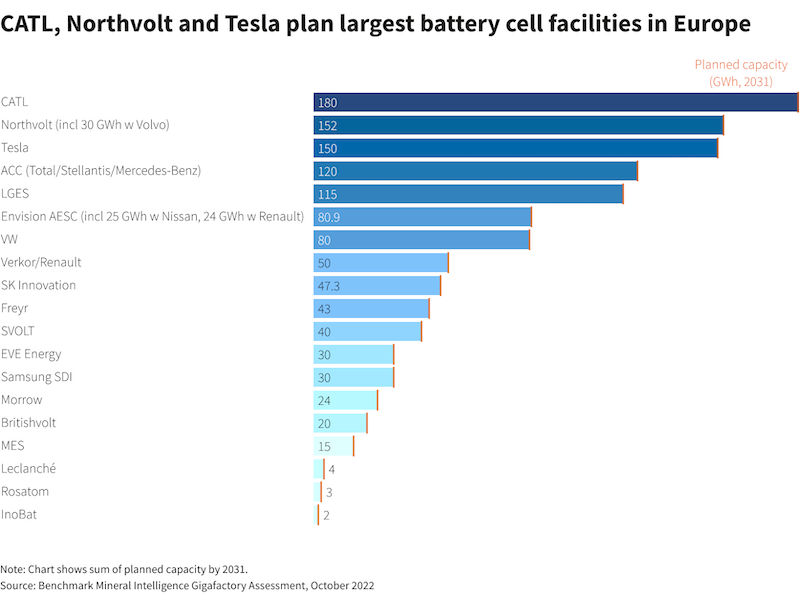

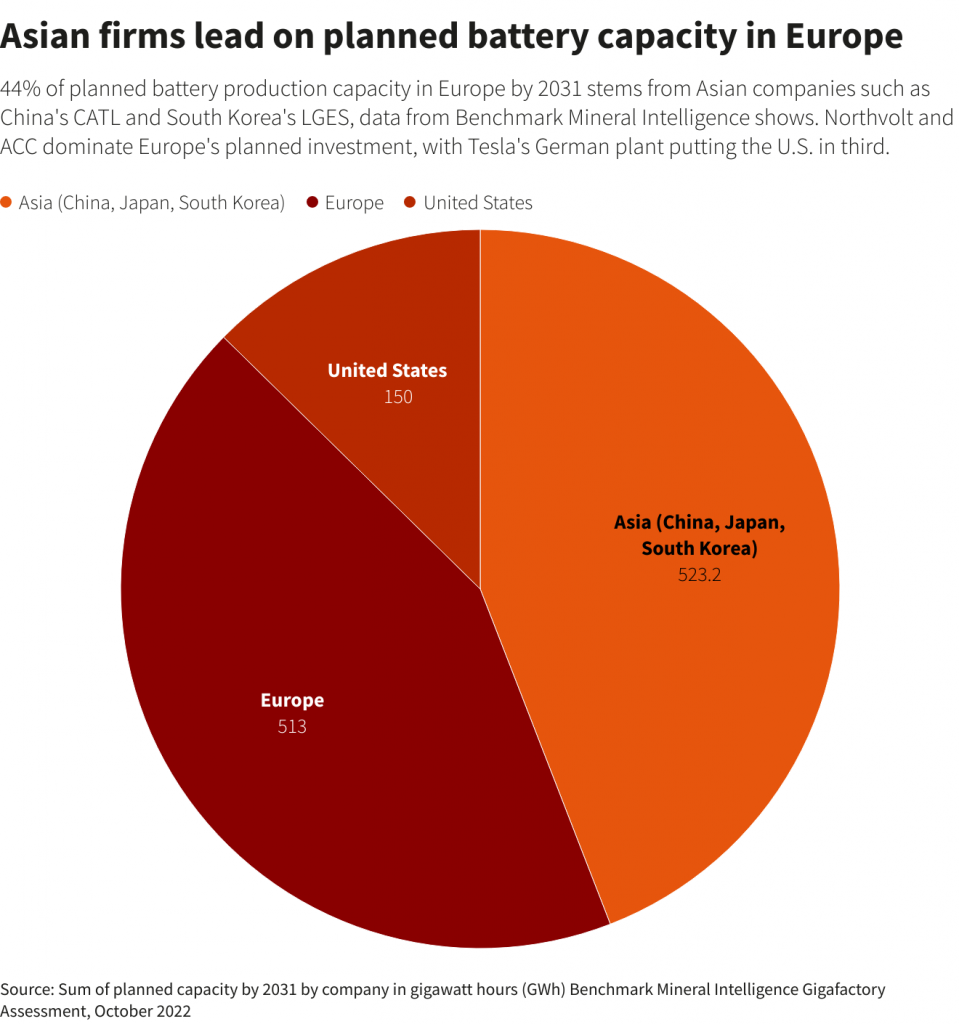

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (BMI) estimates that Europe should have a manufacturing capacity of 1,200 GWh by 2031 if current plans come to fruition, outstripping expected demand of 875 GWh.

But of that 1,200 GWh, 44% will be provided by Asian companies with factories in Europe, ahead of homegrown firms on 43% and Tesla with 13%, according to calculations based on BMI data.

What’s more, Caspar Rawles, BMI’s chief data officer, said some of the plants being planned by European companies “won’t ever make it off the drawing board”.

That’s because the Chinese, South Korean and Japanese firms that dominate the market are more likely to follow through, as they already have contracts with global carmakers and experience building large factories around the world, he said.

“The vast majority of European capacity is going to be Asian,” Rawles said.

European carmakers BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Stellantis and Volkswagen have all signed offtake agreements from plants under construction by Asian players, such as China’s CATL and South Korea’s LG Energy Solution.

And China’s Envision AESC, for example, is already considering building more plants in Europe.

The European Battery Alliance (EBA) acknowledges Asian firms, and Chinese companies in particular, are likely to increase their market share in the coming years, helped by their track record and offtake agreements.

Britishvolt is just one of the startups with grand ambitions to run into trouble. It wants 3.8 billion pounds ($4.4 billion) to build a gigafactory in northern England but its plans are hanging by a thread as it struggles to lure enough investment.

Unlike Northvolt, which formed a joint venture with German carmaker Volkswagen in 2019 and struck a long-term supply deal with BMW in 2020, Britishvolt has yet to sign any major customers or test its technology on a commercial scale.

“Nobody will give you an order on the strength of a PowerPoint,” said David Roberts, who has invested in several British firms to focus on zero-emission cars. “You’re looking at six years before you have real sales, so where the hell do you get $5-billion-plus operating costs without an order?”

That’s why a number of European startups are taking the slower route, building smaller, cheaper plants with a capacity below 1 gigawatt-hour (GWh) – dubbed “megafactories” – to produce cells at scale and then win contracts from carmakers.

French battery startup Verkor, for example, announced on Wednesday that it had raised 250 million euros ($249 million) to fund a megafactory.

Chief executive Benoit Lemaignan described it as a “baby step”, before the company embarks on raising funds for a 1.6 billion euro 16 GWh gigafactory that should open in 2025 and will supply French carmaker Renault.

‘A Long and Winding Road’

“The European Commission and the member states should be aware that if we want to have at least some resilience, knowledge and know-how in battery production, you need to have some domestic supply,” EBA policy manager Ilka von Dalwigk said.

“Even if we have the production in Europe, it doesn’t mean we have the know-how or the control,” she said. “For the moment we see Northvolt – but as for the other initiatives, there is still a long and winding road to go.”

Besides Northvolt, which delivered its first lithium-ion batteries from its Swedish gigafactory this year, another homegrown company is Automotive Cells Company (ACC), a venture between French energy giant TotalEnergies, Stellantis and Mercedes-Benz.

ACC is aiming for a capacity of 120 GWh by 2030, requiring 7 billion euros in equity, debt and subsidies, but its first gigafactory in northern France is still under construction.

Italvolt is aiming to build a 3.5 billion euro gigafactory in northern Italy. It has not announced any fundraising plans yet but said that a joint venture would get the plant off the ground, promising further details soon.

Other startups taking the slower route to gigafactories include Slovakia’s InoBat. It will open a 45 megawatt-hour (MWh) pilot line in Bratislava early next year to produce high-performance batteries for customers to test and has signed deals, including with German air taxi developer Lilium, worth 500 million euros by 2030, CEO Marian Bocek said.

He said InoBat had a pipeline of potential agreements worth 25 billion euros and aims to build production capacity in 4 GWh increments starting in 2025 – costing up to 400 million euros each – as contracts are signed.

“You don’t have to raise billions of dollars, you basically raise money for the offtakes you sign on the back of bankable customers,” Bocek said.

German startup Theion is developing lithium sulphur batteries and chief executive Ulrich Ehmes said the startup aims to raise 50 million euros for a small plant to build samples for automotive and aerospace companies – and then seek funds for a first gigafactory of up to 20 GWh.

‘Hard to Compete on Cost’

Another startup with a gigafactory in its sights is Britain’s Ilika, which makes small solid-state batteries for “electroceuticals”, or medical implants, for the US market at a small plant in Romsey in southern England.

Chief executive Graeme Purdy said Ilika would seek a joint venture with a US manufacturer for mass production of the small cells and will take the same approach for its EV battery project “Goliath.”

The startup will build a megafactory, likely in partnership with a carmaker, then seek a joint venture or licence the technology to a battery maker to make at a gigafactory, rather than try to raise billions itself.

“It’s a big ask,” Purdy said. “Rather than trying to reinvent wheels on our way to doing that, we’d rather work with an organization that has done it previously.”

British sodium-ion battery startup Faradion, meanwhile, has chosen a different route, selling out to Indian conglomerate Reliance Industries last year for an enterprise value of 100 million pounds. Reliance is aiming to build a 50 GWh plant in India.

“When you have a new chemistry like this, you need a champion behind it,” Faradion chief executive James Quinn said.

The EU has approved 6.1 billion euros since 2019 in funding by member states for battery research and innovation while Britain has a 1-billion-pound fund to support investments in EV supply chains. Some are looking for more help from politicians.

InoBat’s Bocek said he was lobbying Brussels to favour EV batteries developed and designed by European firms – using local raw materials wherever possible – similar to the approach adopted by the US to encourage domestic production with its Inflation Reduction Act.

“We cannot compete with the Chinese on cost,” said Bocek. “But we can compete when it comes to a localised value chain.”

- Reuters with additional editing by Jim Pollard

ALSO SEE:

China Years Ahead of Europe in EV Materials Production – FT

China’s Top EV Battery Makers Lose Their Market Share – SCMP

Toyota to Triple Spending on EV Battery Plant in US

China’s Reliance on Foreign Battery Metals a ‘Risk to EV Sector’