British oil giant BP is abandoning its plan to cut back its oil and gas output and planning fresh fossil fuel investments, all while pushing for billions of dollars in government subsidies for climate technologies.

The firm’s plan to quit on its pledge from just four years ago was reported by Reuters, which cited sources with knowledge of the matter.

Retracting from the pledge was part of a larger plan by the company’s newly appointed CEO Murray Auchincloss to scale back the fossil fuel giant’s energy transition, Reuters said in the report published this week.

Also on AF: Floods or Drought: Climate Change Worsens Global Water Woes

Auchincloss hopes to ‘regain investor confidence’ in BP — whose London-listed shares are down nearly 13% this year — by investing ‘first and foremost in oil and gas,’ it said.

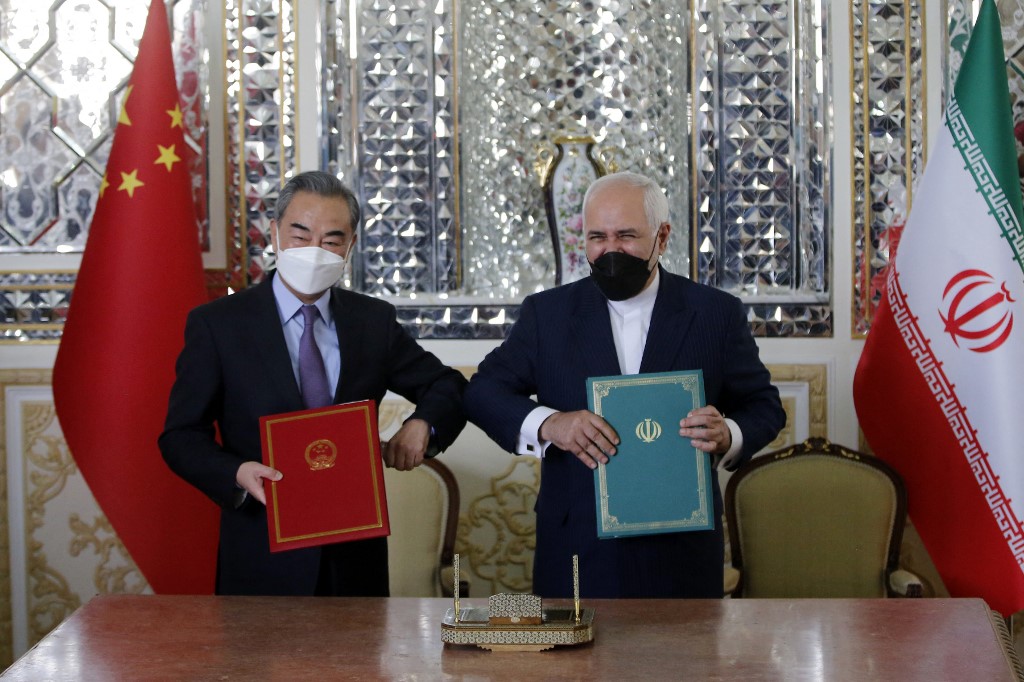

As part of that aim, BP is planning fresh investments in the Middle East, including three new projects Iraq and oil fields in Kuwait. Investments in Iraq will be especially lucrative for BP as, unlike historic contracts, the Iraqi government will share with it profits from developing the giant Kirkuk oil and gas fields.

And yet, on the same day as the Reuters report, The Guardian reported that BP was among the three main companies that lobbied the UK government last year to dole out £22 billion ($28.8 billion) worth of subsidies for carbon capture technology.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is one of the several technologies being developed to combat greenhouse gas emissions and combat climate change.

Last week, the British government agreed to hand out those subsidies. Aside from BP, the other firms lobbying the government were also oil and gas producers — Equinor and ExxonMobil.

Why it matters

BP’s pledge to cut back fossil fuel output was one of the first such announcements by a major oil company. The firm vowed to cut hydrocarbon production by 40% by 2030, achieve zero net emissions by 2050, and invest billions in renewable and low-carbon power.

But that pledge came at a time when Covid-19 sent global oil prices into negative territory for the first time in history and uncertainty loomed about when global economies would manage to recover from the pandemic.

Things changed drastically in the summer of 2022 when Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine and Western nations decided to cut off their ties with Moscow. Europe — which was heavily reliant on Russia for its energy needs — saw energy prices spike.

The result was a bonanza for oil giants. BP raked in nearly $28 billion in profits — the biggest ever in its 114-year history.

The company has since been scaling back its transition plans. While chief Auchincloss is yet to formally announce the complete removal of the reduced output target, a source told Reuters BP had “in practice… already abandoned it.”

On its website, meanwhile, BP maintains it plans to reach net zero by 2050 “or sooner” and stay on a path “consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement.”

But its plans for new investments in fossil fuels are a stark contrast to that pledge. Scientists, such as those at the International Energy Agency, say that all new oil and gas exploration and expansion needs to stop immediately for the world to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Furthermore, BP’s investments in renewables and “low carbon energy” have “flatlined”, according to Energy Monitor.

Giving climate tech a bad name

BP’s increased lobbying for climate subsidies, despite that contradictory approach, brings into focus increasing criticism for planet-saving technologies due to their links with the fossil-fuel industry.

For years oil and gas companies have hailed carbon capture and storage (CCS) as a way to cut back on their fossil fuel emissions. The technology can be used to collect and store CO2 emissions from carbon-intensive operations.

But climate watchdogs and advocates have consistently warned, since at least as far back as 2019, that CCS is merely a smokescreen for oil and gas giants looking to expand their production and fossil fuel exploration.

Oil firms actually developed carbon capture know-how to improve their production by way of enhanced oil recovery (EOR). The process — first used in 1972 — uses captured carbon to extract additional oil out of a production well.

The fossil fuel industry’s proficiency in developing the technology over the years means most governments are inclined to include them in policy discussions on CCS, one expert told The Guardian.

“But that might create a risk whereby these companies unduly influence policy and rollout in a way that benefits them,” the expert added.

Meanwhile, giants like BP have also continued to bump up their oil production, banking simply on CCS to “reduce their emissions”. That, coupled with the high energy demands of CCS infrastructure at present, means the continued use of the technology by fossil fuel firms ends up generating far more emissions.

IEA chief Fatih Birol warned last year that “continuing with business-as-usual for oil and gas while hoping a vast deployment of carbon capture will cut the emissions is fantasy.”

It is also worth noting that internal BP documents recently subpoenaed by the US Senate show the company’s officials know of the technology’s shortcomings. They also show BP knows it has other methods to reduce emissions, such as “reining in flaring and methane leaks, and supplanting coal usage in Asia with natural gas.”

Nevertheless, the problematic association of CCS with the fossil fuel industry has led activists such as Harjeet Singh, global engagement director for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, to term subsidies for CCS development as a “colossal waste of money”.

“It is nothing short of a travesty that funds meant to combat climate change are instead bolstering the very industries driving it,” Singh told The Guardian.

But on the other side of the spectrum, policymakers and agencies like the IEA and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) argue that the world will need every tool it can possibly use to limit global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

In fact, the IEA has called on the oil and gas industry to develop clean energy technologies like CCS at scale and bring down their costs as it possesses the qualities necessary to do so. CCS, in particular, has a long way to go due to its still low emission reductions and significant set-up costs.

But continued development of CCS is particularly important for tackling CO2 from the sectors where emissions are hardest to reduce, like steel and concrete, the IEA and IPCC say.

But what about the shareholders?

Despite these concerns, one might argue that the primary responsibility of a company’s CEO is to act in the best interest of its shareholders — which Auchincloss may seem to be doing.

But while scaling back its energy transition might give BP’s stock a temporary breather — it may not do much for the company’s shareholders over the longer term.

According to IEA estimates, if global governments remain committed to net-zero goals, fossil fuel demand would fall between 45% and 75%. Meanwhile, the current valuation of private oil and gas companies could drop by 25% to 60%.

Given that scenario, continued fossil fuel investments will leave an eye-watering $557 trillion worth of assets at risk of being left ‘stranded’, according to a study by the UK’s Exeter and Lancaster Universities.

Stranded assets refer to infrastructure like gas pipelines and oil refineries that will be rendered useless before the end of their economic life as the world races to achieve its net-zero goals.

Losses from such stranded assets will be borne by retail and institutional investors that hold stocks of fossil fuel companies, as they will likely see prices of their shares and bonds diminish overtime due to the growth of renewables, according to the London School of Economics.

It would make “practical sense, not just ethical sense, to embrace the transition now rather than resist it,” researchers in the UK study concluded.

View this post on Instagram

- Vishakha Saxena

Also read:

‘Wealthy Nations’ Fossil Fuel Deals Threaten a Global Catastrophe’

LNG’s Carbon Footprint 33% Bigger Than Coal’s – CC

Continuing Rise of Methane Emissions Worrying Top Scientists

Booming Solar Puts 2030 Renewable Energy Goals ‘Within Reach’

Oil And Gas Sector Way Off Net Zero Track: S&P Global

Indian Oil Tycoon Says New Energy Will Earn As Much As Refineries

Oil Nations Blocking COP29 Efforts on Fossil Fuel Phaseout – FT

Green Investment Hindered by Poor Demand For Low-Carbon Products

Governments Spend $2.6tn on Climate-Harming Support – Guardian

Electrification Cuts Oil, Gas Production Emissions by 80%

Australian Extensions for Coal Mines Angers Pacific States

Extreme Weather Cost China More Than $10 Billion In July Alone