China’s Communist Party members face major challenges as they prepare to meet in Beijing for their five-yearly Congress.

Xi Jinping looks set to extend his tenure as China’s supreme leader, but he faces great tests – a sharp economic slowdown, elevated geopolitical tensions with the West, and the need for a swift transition to renewable energy.

With youth unemployment at record highs, growth near historic lows, a property crisis and eye-watering debt levels, Xi also needs to rethink the economic model that underpinned its impressive expansion over the past four decades but is now unsustainable.

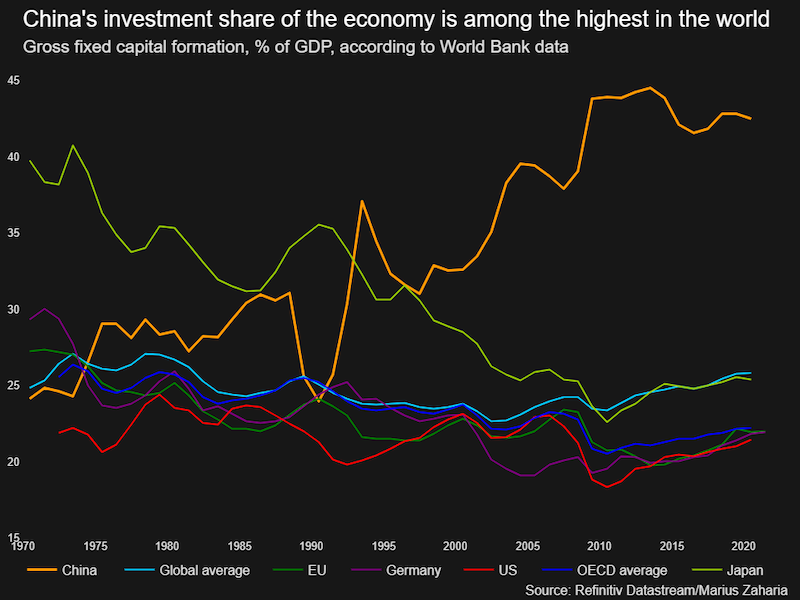

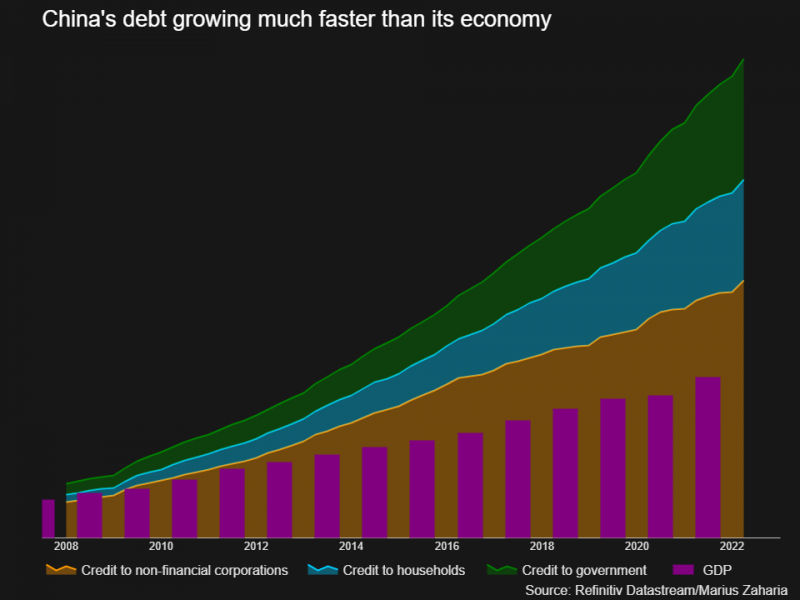

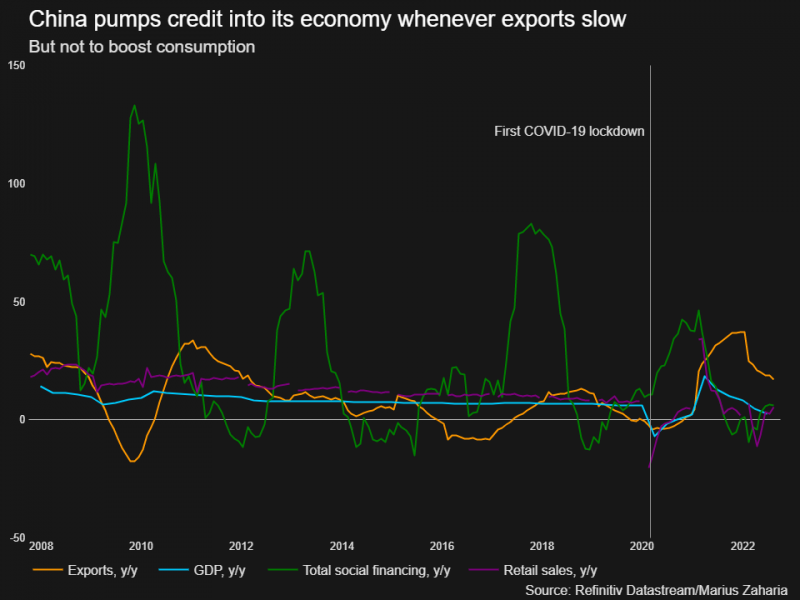

Many economists say its growth over the past 10-15 years has relied too heavily on construction and investment as sources of demand to achieve ambitious annual targets, with debt sky-rocketing as a result.

With those wells drying up, a sharp slowdown is inevitable, economists say, roughing the seas the world’s No-2 superpower will have to navigate under Xi’s next mandate.

Michael Pettis, professor of finance at Peking University in Beijing, said while many economies have followed an investment-driven development model, China’s reliance on it was extreme.

“You cannot invest 40-45% of gross domestic product (GDP) forever. China has to prepare itself for many, many years of much slower but sustainable growth,” Pettis said. “Those who expect the Chinese economy to be the largest in the world by 2035 will almost certainly be disappointed.”

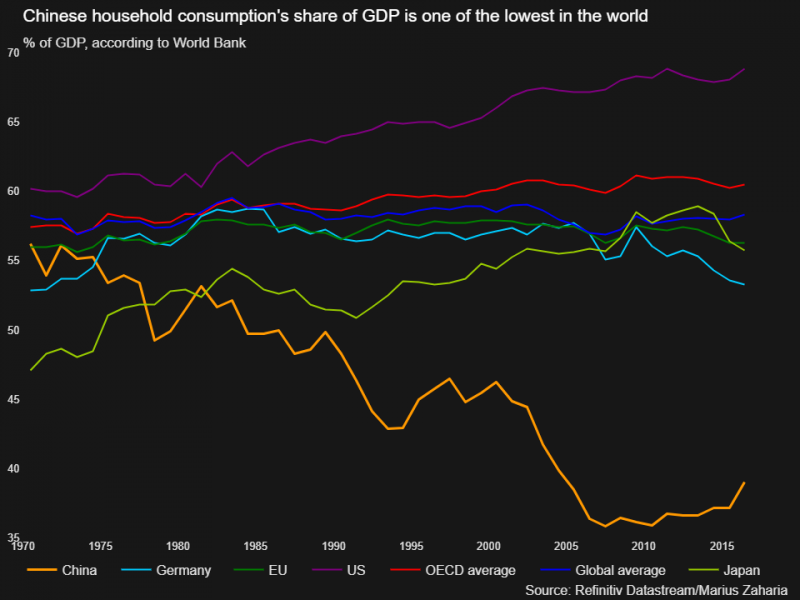

World Bank data shows investment as a share of China’s GDP is almost 20 percentage points above the global average, while household consumption is almost 20 points below.

China’s blistering pace of domestic investment has built the world’s largest network of high-speed railways, most of the world’s 10 longest bridges, the world’s busiest ports but also, by some estimates, 50 million empty apartments – enough to house the entire population of France.

That investment-consumption imbalance is deeper than it was in Japan in the 1980s, before its infamous “lost decades”, and with China accumulating total debt worth almost three times GDP.

One former and two current Chinese government advisers said while policymakers recognised the need to ramp up domestic consumption, it was seen more as a long-term goal, not an emergency.

Jia Kang, who runs the China Academy of New Supply-Side Economics, says the immediate problem was “weak confidence”, including among consumers, and that investment was still needed short-term.

“If there is no investment, consumption will be like a tree without roots,” said Jia, who previously led a finance ministry think tank.

China in recent months has already cut interest rates, approved infrastructure projects and given banks new quotas to fund them. To prop up the distressed property sector, many cities have reduced downpayments and eased mortgage rates.

The National Development and Reform Commission, China’s macroeconomic management agency, did not respond to requests for comment.

Boom and Bust

Decades of state ownership and central planning under Mao Zedong left China rural and impoverished, with only basic manufacturing and dire infrastructure.

In 1978, under Deng Xiaoping, China changed course, allowing more private enterprise and ownership, opening the economy to foreign trade and investment and incentivising savings.

Local governments made money leasing land to developers, which, in a rapidly urbanising China, sold ever more flats at ever higher prices.

Policy focused predominantly on supply, not demand. The government spent money on roads, railways and airports, while banks lent more to strategic, state-dominated industries than to consumers.

As China opened to the world, factories took advantage of cheap labour and special economic zones to build tight logistics chains, making the country a manufacturing superpower.

To offset cratering external demand during the 2008-09 global financial crisis, China borrowed aggressively to double down on infrastructure.

In the decade to 2020, China consumed almost 25 times more cement than the United States. By 2021, state-owned China State Railway Group had 5.92 trillion yuan ($825.66 billion) in liabilities, more than the GDP of Saudi Arabia.

In the property market, which now accounts for a quarter of China’s economic activity, businesses took more risks and banks offered mortgages before flats were built, leading to massive oversupply.

Many developers, like China Evergrande, paid suppliers in commercial paper instead of cash, so when it defaulted, its supply chain collapsed.

One business owner who spoke on the condition of anonymity said his firm at its peak made 150 million yuan a year supplying promotional materials to Evergrande. He now lives in a dormitory and earns 3,000 yuan a month working in a screw factory.

A New Model?

Many uncertainties hang over China’s economy: the zero-Covid policy, a crackdown on tech and other industries, geopolitical tensions and rising borrowing costs in export markets.

A complete re-modelling is therefore not imminent, government advisers say.

“We should consider consumption from a medium- and long-term perspective,” cabinet adviser Yao Jingyuan said.

But China now needs seven units of additional investment, up from three in the 1990s, to generate one unit of GDP, Oxford Economics lead economist Adam Slater says.

Using investment, even to dress the latest wounds, will only mean more debt.

And with indebted local governments starved of cash as plummeting land sales hit revenues, heavy infrastructure spending seems an unlikely fix for slowing growth.

China is widely expected to miss this year’s 5.5% GDP growth target and Natixis estimates growth may not even top 3% a year into Xi’s next mandate.

Oxford Economics expects average annual GDP growth this decade to halve from the 1999-2019 average to 4.5% and slow to 3% in the decade after. This puts China’s GDP-per-head at less than a third of the United States’ in 2040, they said.

The Communist Party has built its legitimacy on delivering high growth. A slowdown could challenge that.

Economists say more policy support for households will make a transition to consumption-led growth less painful, although it’s unlikely to fully account for reduced investment.

Policymakers’ options include cutting sales taxes, encouraging wage growth, raising pensions and unemployment benefits, or subsidising medical treatment and other social services.

But no such moves are imminent.

Zhiwu Chen, Professor of Finance at the University of Hong Kong, says street protests in Henan province over a banking scandal and recent mortgage boycotts point to what China may face in the next decade.

“We are in this growth slowdown phase, and maybe eventually, China will experience recessions or other crises,” he said. “As that happens, social unrest and injustice will take place much more frequently.”

Another wildcard is China’s lethargic response to global warming, which is now causing considerable economic harm. Some foreign observers say the country would be better to focus state spending on a rejig of its power grid to speed up the switch from coal power to renewable energy.

- Reuters with additional editing by Jim Pollard

ALSO SEE:

China’s Leadership Reshuffle: Candidates for Premier, Politburo

Investors Losing Confidence in China, EU Chamber Says

Can China Evergrande Save Itself With Debt Restructure?

China Think Tank Urges Scrapping of ‘Zero Covid’ Policy – AP

Two China Provinces to Repay Depositors After Rare Protests