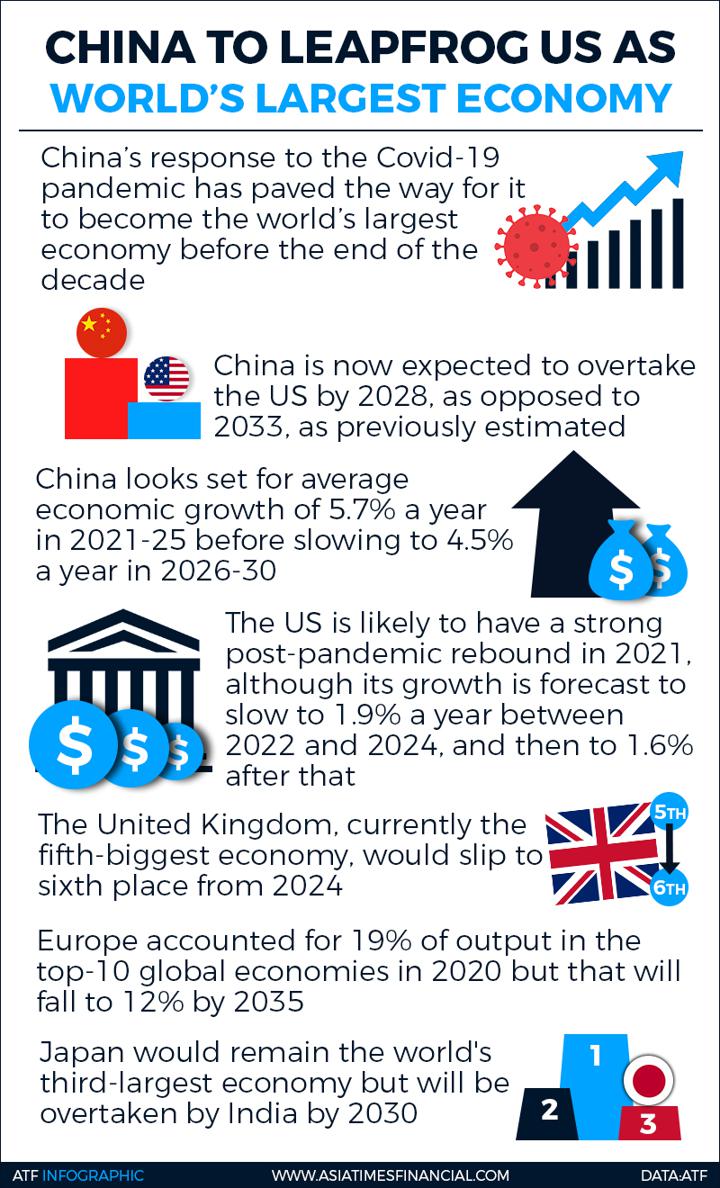

(ATF) Its economy is recovering impressively, its financial markets are buoyant and it has strengthened its regional clout: China goes into 2021 in a much more enviable position than President Xi Jinping could have dared hope at the height of the coronavirus crisis.

If any country can be said to have had a good pandemic it is China. By imposing fierce early lockdowns and grabbing opportunities thrown up by the West, China has turned adversity to its advantage. Mocking US trade tariffs and sanctions against its tech companies, China has notched up record trade surpluses and is the only major economy to have expanded this year. It is also forecast to grow faster than its peers in 2021.

The Communist Party’s secrecy when Covid broke out in Wuhan drew international criticism, but its efficient handling of the pandemic subsequently has given Xi confidence to press ahead with a number of difficult reforms that are set to dominate policy-making in the year ahead.

First, outgoing US President Donald Trump’s campaign to penalise China’s exports and thwart its technological ambitions has made Xi determined to rely more on domestic demand and to depend less on global supply chains dominated by US multinational firms. Expect more programmes in 2021 to support this “dual circulation” strategy like the huge efforts underway to build capacity in advanced microchip manufacturing.

Second, the pandemic triggered a burst of government spending, notably on infrastructure, to bolster jobs and incomes. Now that the need for emergency fiscal support has receded, Beijing is refocusing on the imperative of stabilising national debt as a percentage of output. To that end, more “controlled” defaults by state-owned firms and local governments are probable in 2021 as the authorities inject more discipline into the credit markets.

Third, even as it retains a firm grip on capital outflows, Beijing’s eagerness to professionalise its financial markets means it is likely to keep encouraging foreign portfolio investors and financial institutions to set up shop in China.

Overseas capital has poured into mainland financial assets this year. Chinese stocks are among the best performers globally and the renminbi is one of the strongest currencies. Barring a big market scandal or crisis, expect Beijing to keep the welcome mat rolled out as it seeks to show that it is not turning its back on the global economy.

The solid platform that China has constructed for the economy in 2021 is primarily due to its own efforts in containing the coronavirus. But it has also benefited indirectly from the West’s approach to the pandemic.

Authoritarian surveillance state

As an authoritarian surveillance state, China was able to close down vast swathes of the economy and to prevent people’s movements with a ruthlessness that Western democracies either could not or would not countenance.

So, whereas Chinese factories were able to reopen quickly, Western economies have been in a stop-go stutter of lockdown followed by relaxation followed by renewed tightening. The virus is still out of control. The result is that many people are still working at home, fuelling demand for everything from computers to furniture, much of it produced in China – to say nothing about panic buying of personal protection equipment and other medical kit.

The West’s monetary policy response has also helped Chinese asset markets. While the People’s Bank of China opted for targeted help for banks rather than slashing interest rates, the Federal Reserve and other Western central banks injected unprecedented amounts of cash into their financial systems, driving interest rates sharply lower. This enhanced the yield appeal of Chinese bonds and boosted the renminbi.

Beijing has also seized, opportunistically, on the geo-economic openings afforded by Trump’s animus towards China. One of his administration’s first acts in 2017 was to pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an ambitious framework for free trade in the Asia-Pacific that was a cornerstone of his predecessor Barack Obama’s plans to counter Chinese influence in the region.

Although the TPP was rescued at Japan’s initiative, America’s withdrawal created a vacuum that China has happily filled by helping create the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a grouping of 15 countries numbering about 2.2 billion people with combined output of about $26 trillion.

RCEP has been criticised for being a shallow agreement that will do little to boost trade. Perhaps. But it would be unwise to overlook two important features of the pact, which was signed in November.

First, it binds China, Japan and South Korea together in a trade agreement for the first time. This will give Japanese and Korean firms greater access to the huge China market and make it easier for them to organise production across Southeast Asia to take advantage of lower costs.

And second, by harmonising rules of origin and investment provisions in existing free trade deals, it hastens the emergence of an Asian trading bloc. This is a strategic priority for Xi, who envisions China at the heart of a web of regional, increasingly “de-Americanised” supply chains. As economic links with China grow, so, too, Beijing hopes, will its political influence. The same thinking underpins Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative.

Deal with EU

China will take another step towards this goal if and when it concludes long-running negotiations with the European Union over a bilateral investment treaty (BIT).

Recognising that a China-EU BIT would further marginalise the US in the Asia-Pacific, incoming President Joe Biden’s national security adviser has urged Europe to hang fire pending consultations with the new administration.

Of course, China still faces powerful headwinds. Technological decoupling is set to continue. Biden, who called Xi a “thug” during the election campaign, is likely to keep Trump’s sanctions against Huawei and other firms deemed to be Trojan horses for the Chinese intelligence services.

And Covid-19 is not yet defeated. A new, more infectious strain of the virus is spreading rapidly, triggering fresh lockdowns across the globe. Mass vaccination will take months.

When asked what was most likely to trouble his government, the late British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan supposedly replied: “Events, my dear boy, events.” Covid-19 is a supreme example. China has so far risen to the challenge and is in a confident, assertive mood. But as he prepares to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party next July, Xi will be hoping 2021 is event-free.