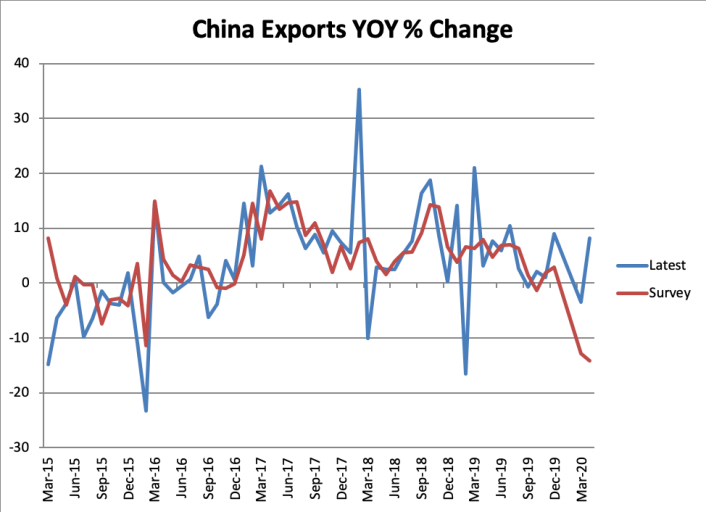

China’s March export value rose 8.5% year on year, diverging widely from analyst forecasts which foresaw a 12% decline. Strong exports growth to Asia, and especially Southeast Asia, fed the unexpected improvement.

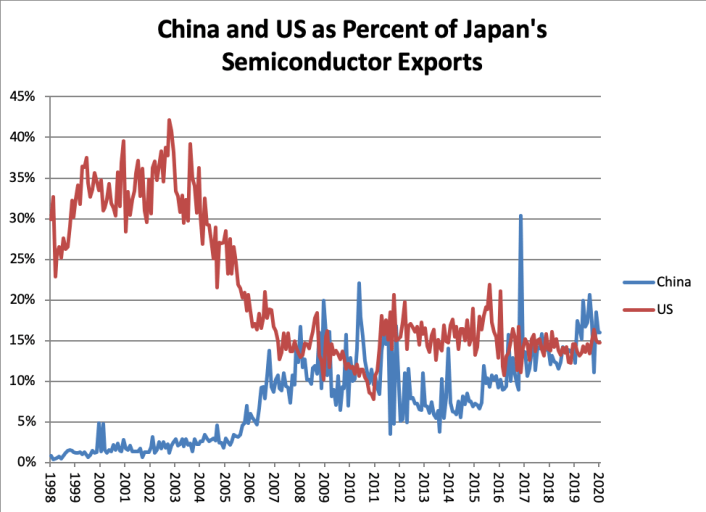

The March data denote a steady increase in Asian economic integration, in which a larger portion of Asian trade is directed towards Asia itself. While America contemplates decoupling from China, it seems that Asia is decoupling from the United States. Since the US-China tech war began in April 2018 with Washington’s ban on chip exports to China’s ZTE Corporation, “de-Americanization of supply chains” has been the buzzword in the semiconductor industry.

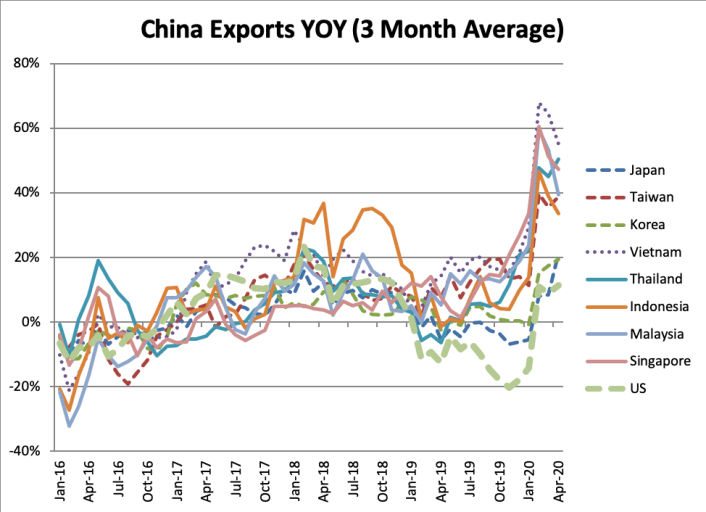

Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia purchased about 50% more Chinese products in April 2020 than they did in the year-earlier month. Japan and Korea showed 20% gains. Exports to the US rose year-on-year, but from a very low 2019 base.

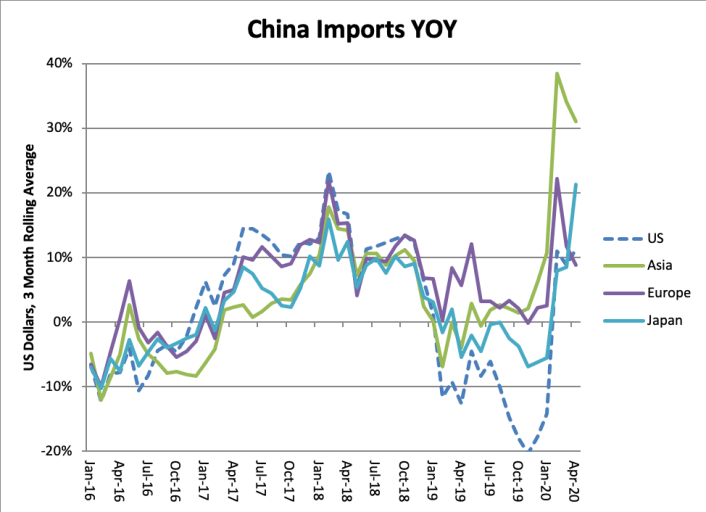

China’s imports from Asia also rose sharply.

The sharp increase in intra-Asian trade may reflect the re-start of Asian economies. A combination of massive testing, digital surveillance, and social solidarity kept death rates from Covid-19 at less than 10 per million of population in most of Asia, vs hundreds of deaths in the United States and most of Europe.

Most of China’s manufacturing economy now above 90% of capacity. The re-opening of supply chains explains a good deal of the surge in both imports and exports. Nonetheless, the strong two-day data set in relief the growing integration of the major Asian economies.

A shift in supply chains away from the United States, though, probably accounts for some of the jump in Asian trade. Japan now ships more semiconductors to China than it does to the United States. As late as 2014, Japan sold three times as many semiconductors to the US than to China.

A small part of the import surge can be explained by Chinese stockpiling of semiconductors as a precaution against American exercise of the “nuclear option” against China’s telecommunications giant Huawei. The US might forbid foreign companies to sell computer chips to Huawei if they use American equipment to fabricate them. That would in theory prevent Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation, the world’s largest chip fabricator, from selling to Huawei, now TSMC’s biggest customer with 13% of total sales. Huawei’s chip-design subsidiary HiSilicon now ranks among the world’s top 10 chipmakers, and its domestic sales in the first quarter exceed those of Qualcomm. But HiSilicon cannot manufacture its own chips, and China’s onshore chipmaking capacity cannot provide the top-of-the-line chips that Huawei puts into its high-end smartphones and servers.

US technology companies persuaded the Trump Administration not to try to bar Huawei from access to Taiwanese and other foreign chips, arguing that the measure would delay but not prevent China from achieving self-sufficiency. In the meantime, American firms would lose market share in China – as Qualcomm and Nvdia already have lost to HiSilicon – while the rest of the world would scramble to remove as much American content as possible from the supply chain. That would be a difficult and costly exercise, as the Hinrich Foundation argued in a January 2020 report.

The Hinrich report argues, “The risks of facing more draconian US extraterritorial laws, including those that fall under the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) – especially as the US dollar remains the predominant international currency – means that even a simple financial transaction with a restricted entity could be prohibited, thereby killing the business relationship entirely. As such, Huawei and other Chinese tech companies are looking to decouple entirely (or bide their time until it is possible) from US-influenced supply chains. To do this, Chinese firms must form alliances with non-American technology companies.”

This story appeared first on Asia Times website