China’s population fell in 2022 for the first time in more than 60 years, in a historic turn that has profound implications for its economy and the world.

The country’s National Bureau of Statistics announced on Tuesday its population declined by roughly 850,000 to 1.41175 billion at the end of last year.

This is the worst drop in China’s population since 1961, the last year of its Great Famine. Experts predict the decline marks the start of a long period of shrinking citizen numbers in the country.

Also on AF: China’s 2022 Growth of 3% Among the Worst in 50 Years

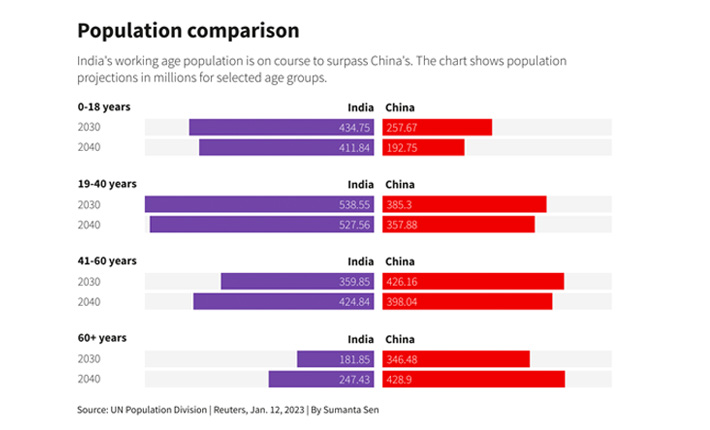

Long-term, UN experts see China’s population shrinking by 109 million by 2050, more than triple the decline of their previous forecast in 2019.

The statistics also lend weight to predictions that India will become the world’s most populous nation this year.

Concern for global economy

Kang Yi, the head of the national statistics bureau, told reporters the fall in population was not a cause for concern as “overall labour supply still exceeds demand”.

But domestic demographers lament that China will get old before it gets rich, slowing the economy as revenues drop and government debt increases due to soaring health and welfare costs.

“China is facing a demographic crisis that far exceeds the imagination of Chinese authorities and the international community,” demographer Yi Fuxian told the Financial Times.

Shrinking labour and a rapidly ageing population are set to impact contributions to the country’s massive pension system. They will also take a toll on China’s debt-ridden property market — one of the most crucial pillars of the world’s second largest economy.

“China will have to adjust its social, economic, defence and foreign policies,” Fuxian said.

He also noted that the country’s shrinking labour force and downturn in manufacturing heft would further exacerbate high prices and high inflation in the United States and Europe.

An abundance of labour has been key to China’s role as the factory floor of the world, powering its manufacturing boom over the past four decades.

“Higher labour costs, driven by the rapidly shrinking labour force, are set to push low-margin, labour-intensive manufacturing out of China to labour-abundant countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh and India,” the World Economic Forum said last year.

One-child policy impact

Much of China’s demographic downturn is the result of the one-child policy imposed between 1980 and 2015 and sky-high education costs that have put many Chinese off having more than one child or even having any at all.

China’s birth rate last year was just 6.77 births per 1,000 people, down from a rate of 7.52 births in 2021 and marking the lowest birth rate on record.

The data was the top trending topic on Chinese social media after the figures were released on Tuesday. One hashtag,”#Is it really important to have offspring?” had hundreds of millions of hits.

“The fundamental reason why women do not want to have children lies not in themselves, but in the failure of society and men to take up the responsibility of raising children. For women who give birth this leads to a serious decline in their quality of life and spiritual life,” posted one netizen with the username Joyful Ned.

China’s stringent zero-Covid policies that were in place for three years have caused further damage to the country’s demographic outlook, population experts have said.

Local governments have since 2021 rolled out measures to encourage people to have more babies, including tax deductions, longer maternity leave and housing subsidies. President Xi Jinping also said in October the government would enact further supportive policies.

The measures so far, however, have done little to arrest the long-term trend.

Online searches for baby strollers on China’s Baidu search engine dropped 17% in 2022 and are down 41% since 2018, while searches for baby bottles are down more than a third since 2018. In contrast, searches for elderly care homes surged eight-fold last year.

The reverse is playing out in India, where Google Trends shows a 15% year-on-year increase in searches for baby bottles in 2022, while searches for cribs rose almost five-fold.

- Reuters, with additional editing by Vishakha Saxena

Also read:

̌Plunging Trade Risks China’s Status as the ‘World’s Factory’

China Reveals 60,000 Covid Deaths After WHO Data Doubts

Youth Unemployment to Hit 23% in China, Bank of America Says

China to Allow Private Pension Investment via Mutual Funds