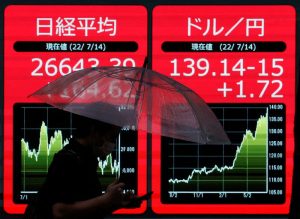

Some local state-owned enterprises (SOE) have defaulted recently, causing a sell-off in the Chinese fixed income market. This means some more short-term upward pressure on Chinese yields, which have gone up to 3.2% and 3.3% for 5-year and 10-year CGB, respectively, from less than 2.0% and 2.5%, respectively, in 2Q20.

This is still within my expectation of a CGB yield range between 3.0% and 3.5% in the coming 12 months when the economic recovery will encourage Beijing to revive its deleveraging policy and structural reforms. These measures will inevitably hurt market sentiment in the short-term but are structurally positive for Chinese assets in the long-term. The PBoC’s job, in my view, is to prevent any credit events from getting out hand and keep liquidity sufficient for yields to hold within this range.

There’s more than meets the eye

The recent defaults by some local SOEs have underscored my view that Beijing is confident with this recovery’s staying power and is, thus, reviving its deleveraging policy and its gradual retreat from the implicit guarantee policy distortion. Of course, there is a policy risk of being overly confident in the system’s resilience and the Covid-19 shock could return. But on balance, the PBoC is still sticking with its neutral policy gun, as the steady cyclical recovery is offsetting the dragging impact from local SOE defaults.

Crucially, it is far from certain that all local governments in China are withdrawing support for their SOEs. The recent local SOE defaults have mainly been in north China (often seen as the rust belt of China), notably in two provinces, Liaoning and Henan. Other provinces, notably Shanxi, Guizhou and Beijing, have intervened to keep their support for their SOEs.

Not withdrawing from support

Coal mining companies from Shanxi province also suffered a sell-off recently as the worries mount, but the provincial government responded quickly by announcing that it would offer full support for all local SOEs to prevent them from failing.

Meanwhile, the Beijing municipal government has also pledged full support for its SOEs. Guizhou is less developed than most other provinces and has very high leverage, but it has so far avoided defaults as its government has been very proactive in coming up with restructuring plans to keep market confidence.

Although in Henan, where the most recent SOE default happened, its provincial government has remained silent since the default on 10th of November, we cannot rule out the possibility that it might intervene at the end if the market turmoil becomes unsettling.

Beijing’s policy stance

From the PBoC’s perspective, it does not want to be caught in having to clean up the local government bond mess. The recent bond market sell-off is a solvency issue rather than a liquidity issue. If it eases monetary policy, that will be good news for CGBs and high-quality credit issuers but will not help rebuild confidence in the weak local SOEs. But the situation in the local SOE sphere is not so bad yet to require a wholesale monetary bailout.

All this implies Beijing is implementing a managed retreat from its implicit guarantee as a way to deleverage the system by allowing bad companies (including local SOEs) to exit the system. This is structurally positive for the Chinese system, and the macroeconomic impact should be manageable too, though market sentiment will be hurt temporarily as investors are uncertain about where the authorities would draw the line of bailout.

That’s why the PBoC is on a standby mode. If things get out of hand, it would ease decisively, in my view. But these defaults have not affected the economic recovery. So at this point, the PBoC is still sticking with its neutral policy stance.

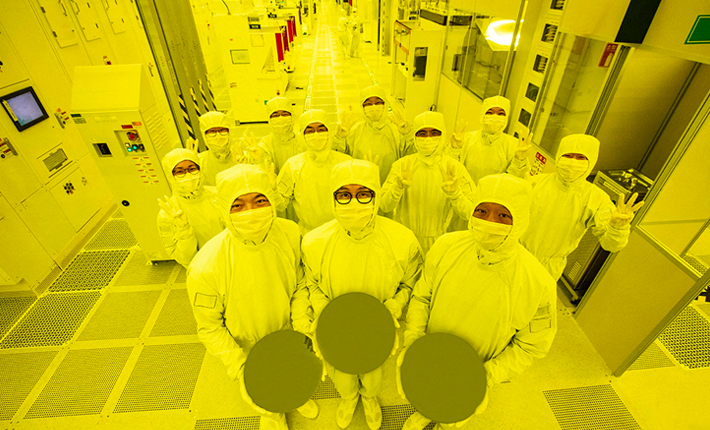

Impact on banks

All this also means that, ceteris paribus, the impact on the Chinese banks will be limited, except those small ones with weak balance sheets. The Chinese banking system is liquid, with still strong public confidence in it. The average capital ratio of the system is more than 10% (more than 14% overall, and more than 10% for tier-1 capital), much more than Basel III requires. But some small banks may be at risk and, looking at recent experience, Beijing is allowing them to fail or be bought by stronger players.