Three years ago India’s scorching solar energy sector was generating a global buzz, but now a plethora of issues including the pandemic threaten its dream of solar power slashing its greenhouse gas emissions

(AF) With a deep desire to decarbonise and a lofty generation target, it is small wonder that India has emerged as one of the world’s top solar markets.

But as the country charts a new renewable energy roadmap to reduce its carbon footprint and promote sustainable economic growth, a host of familiar concerns, from the financial struggles of power distribution companies (known as discoms) to regulatory and policy uncertainties, and steep cost hikes could derail the country’s solar energy dreams.

And the unexpected exit of Softbank’s SB Energy from India last month dealt yet another blow to India’s solar sector. Experts say this has made the prospects for the near future appear “murky”.

Industry sources say the high cost of installation of their projects against tanking solar tariffs is one of the reasons SB Energy gave up on India. “They were very particular about the specifications of their projects and ended up with incurring high capital cost,” Parag Sharma, founder of O2 Power Private Ltd, an independent renewable energy platform, told Asia Financial.

“The biggest problem confronting independent solar power producers is cost escalation of projects, which is making any new installation unviable. Covid issues and the recent spike in prices for all solar plant components have led to an over-25% increase in cost. The entire value chain of India’s solar sector was not geared for that sudden cost increase,” Sharma said.

SB Energy’s exit marks the departure of Softbank, the world’s most ambitious solar investor, which made aggressive bets on renewable energy in India in 2015, when it announced a goal of building 20 gigawatts (GW) of solar power at an estimated cost of $20 billion in the country.

Like many other developers, SoftBank was also hit by unexpected increases in taxes and tariffs, cancellations of auctions and land disputes, experts said.

Decarbonisation roadmap

Under pressure to phase out its coal-fired power plants by the middle of this century to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas, India’s Narendra Modi government surprised the renewable energy world in 2015 by setting startlingly ambitious targets for building new renewable power.

The government said that by 2022, India would build 175 gigawatts of new renewable power, 100 GWof which – equivalent to 25 large nuclear plants – would come from solar. That would have been more than a four-fold increase from the 40 GW of renewable power India had back then.

Six years earlier, India and China were blamed for “sabotaging” a deal at the UN climate talks, so, India’s aggressive solar targets, alongside other renewable energy efforts, such as wind, were seen to benefit not only a country that still uses coal for nearly 60% of its energy mix – but the world’s climate change agenda as well.

The goal confirmed India was now at the centre of global efforts to develop cheaper renewables and tackle climate change.

Initially, the country struggled to build new capacity as quickly as the targets required, but as private power producers raced to grab the opportunity, Indian solar installations grew exponentially over the next two years.

The country added of 9.6 GW in new large-scale and rooftop solar capacity, which was more than double the 4.3 GW installed in 2016 and made 2017 the best year for solar installations in India to date.

The robust growth also boosted the country’s total installed capacity to 19.6 GW by the end December 2017.

Buoyed by that success and driven by its commitment to climate goals, India in 2018 expanded its ambition to target renewable capacity of 450 GW – comprising of 280 GW of solar power – by 2030, to account for 60% of its power needs.

This excluded the 60 GW of hydropower India was also planning to start producing by 2030.

In comparison, the country’s total energy generation capacity today is about 380 gigawatts, out of which 90 gigawatts are of renewable energy, not including large hydropower stations, industry sources say.

According to the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), India would need to generate at least 83% of its electricity from (non-hydropower) renewable energy sources in order to reach net-zero by 2050.

So, while the world is not yet on track to meet its Paris Agreement goals, India had lifted its own goal posts beyond its Paris commitments, and the rest of the world was eager to see its renewable energy plans progress.

Missed opportunity

But fast forward two years and suddenly, the solar energy installations look like a missed opportunity.

According to research firm Bridge to India, the country installed just over 2 GW of solar in Q1 2021 as it rebounded from Covid-related delays, taking the country’s total cumulative solar capacity to 44.2 GW.

The raging second wave of the Covid pandemic though has been a bigger blow to solar investments, as overall investments in the sector declined by 30% with $1.04 billion in the first quarter of 2021, compared to $1.49bn in Q4 2020, according to Mercom India Research India Solar Market Update.

Still, while Q1 in 2021 – with a 33% quarter-on-quarter rise – was a tad more prolific for solar deployment in India due to the deployment of projects delayed in 2020, “the short-term outlook is murky,” Bridge to India says.

Bridge’s forecast for the full year is 13.5 GW of new solar installations, but according to Mercom’s forecast in May, the year would end with only about 7 GW of new plants – down from the 10 GW it forecast earlier this year.

“While India has huge ambitions, given the drop in the demand and the recent lockdown in a number of states in India due to the pandemic, the development of new capacity is likely to take a major hit this year,” Vibhuti Garg, an expert at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), told AF.

To achieve the 2030 goal, India must install about 25 GW of solar capacity every year, these experts say.

Familiar uncertainties

The troubles plaguing India’s solar sector are both macro and structural, “but none of them are new; the uncertainties existed in the past and are quite familiar for the sector,” Jyoti Gulia, founder of JMK Research & Analytics, told AF.

But according to Niti Aayog, the government’s public policy think tank, India lacks a comprehensive national policy and legislative framework for renewable energy. Existing policies and programmes are technology-specific and vary across states, restricting strategic intent.

Aside from willing and creditworthy buyers of renewable energy, financially distressed power distribution companies (Discoms) could also be blamed for the solar slump.

According to CRISIL Research, to reduce heavy dependence on imports of important components such as solar cells, modules and solar inverters, the government has been trying to ramp up domestic manufacturing through various steps including increasing duty on imports.

“For instance, India has recently imposed a basic customs duty (BCD) of 25% on solar cells and 40% on solar modules, and that, along with the production linked incentive scheme (PLI for solar equipment manufacturing), has forced most solar projects to turn to and scout for local equipment, due to which costs of putting up a project has shot up by 20 to 40%,” Hetal Gandhi, director for CRISIL Research told AF.

Although the customs duty will be effective from April next year, the sector still pays a “safeguard duty” of 15% on imports from China and Malaysia, “and with the soaring polysilicon (raw material for solar modules) and all other component prices, most large-scale projects are getting delayed,” Sharma of O2 Power said.

The market for solar components is dominated by Chinese imports, and India imported $2.16 billion worth of solar photovoltaic (PV) cells, panels and modules in 2018/19 – and $2.5 billion in the fiscal year ending 2020.

“The sector’s other problem is, while fierce competition has pushed the solar tariff to a record low, forcing Discoms to turn to solar power over thermal power, in many past power purchase agreements these discoms had entered deals at much higher tariffs,” Hetal Gandhi said.

And now the discoms are in a fix, and reluctant to buy power at the contracted rate, she said.

In early June, the state of Uttar Pradesh cancelled winning bids for 1.84 GW discovered through auctions in February last year, which according to Gandhi, is “a classic example of already bid-out projects facing renegotiation risks.”

According to Gulia of JMK Research, India witnessed two record lows with solar tariffs in last 12 months that led to the tanking of power tariffs to Rs.2 per kilo-watt-hour (2.6 cents), from Rs2.36, the previous low.

CRISIL’s analysis of the current total installed solar generation capacity revealed that nearly 33% of the projects already installed would not be viable at tariffs lower than Rs 3.5 per kilo-watt-hour.

More help wanted

Rattled, private solar power companies now want the government to intervene and help them.

“This uncertainty will not only hinder the foreign direct investments in the sector, but also make foreign investors cautious towards all investments into the power sector, which will affect India’s renewable energy journey and targets,” the National Solar Energy Federation of India (NSEFI) said in a letter last month to the power and renewable energy minister.

The federation added that since February last year, instability in the price of raw materials and an abrupt increase in the prices of PV modules, have hiked up capital costs, and the discoms’ inability to buy power has left most RE power developers cash-strapped.

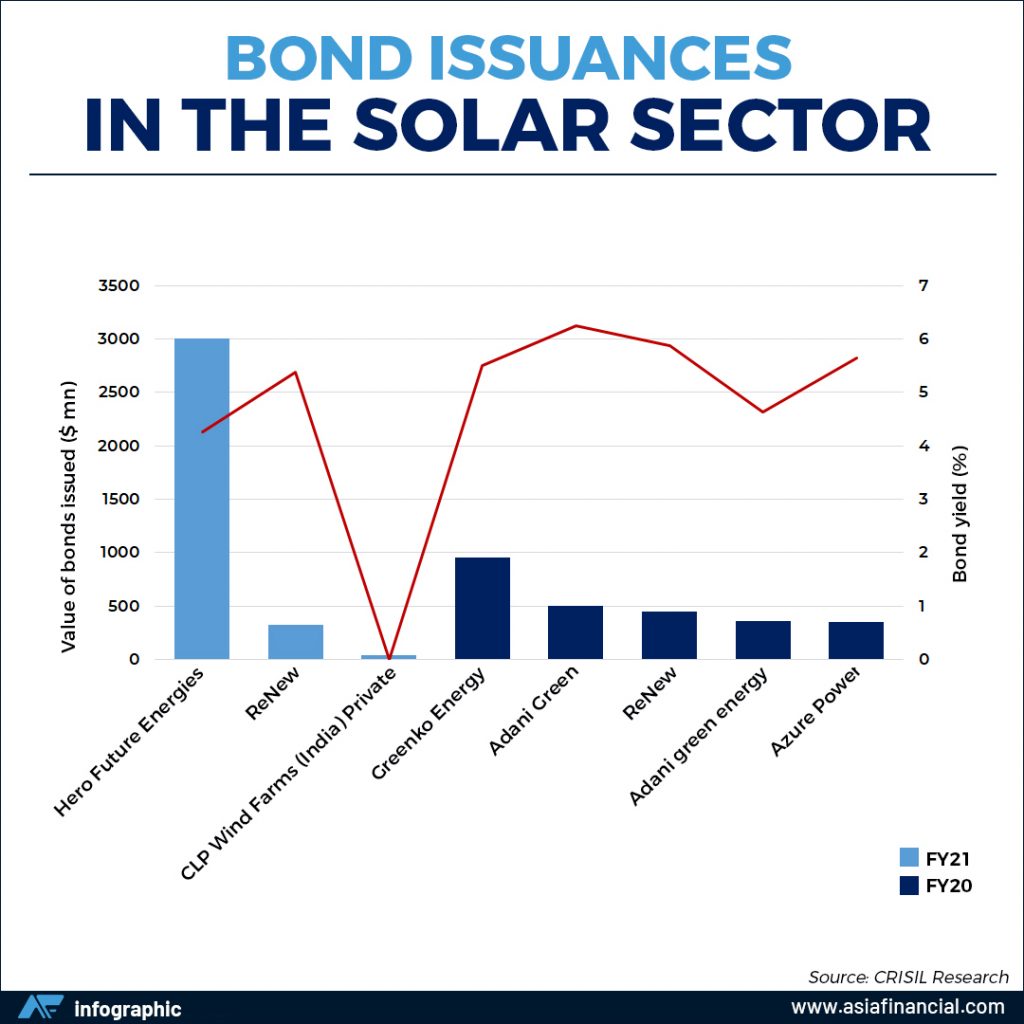

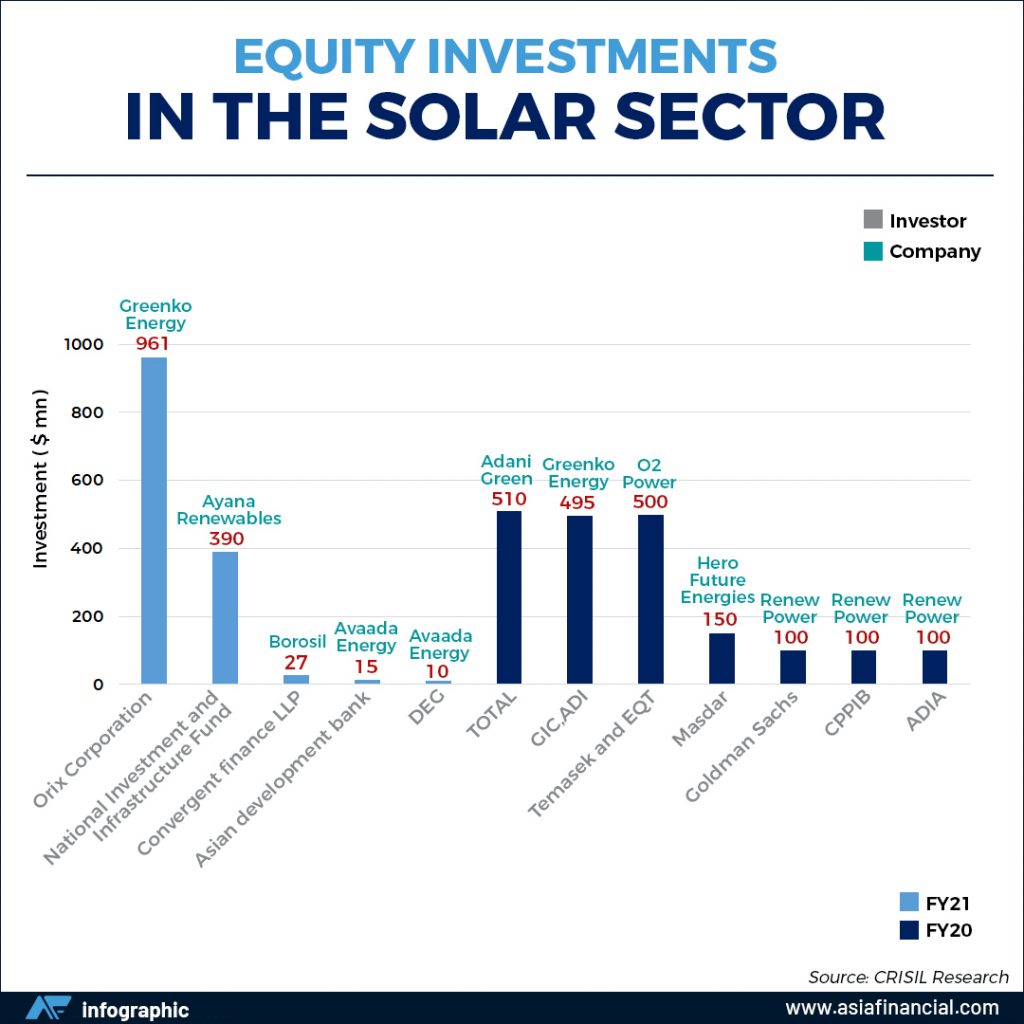

Over the past two years India’s renewable infrastructure sector has experienced significant mergers and acquisitions (M&A), 13 green bond issuances, and spinning-off of operating renewable assets via infrastructure investment trusts (see list).

“This has helped unlock and recycle the existing capital, freeing up project developers’ capital to take on ever-larger tender opportunities,” the IEEFA said in February, adding that the renewable energy sector in India has received more than $42bn in investment since 2014.

But India has mammoth goals to strive for and still requires significant effort and huge amounts of capital to achieve its 2022 target.

IEEFA reckons the sector requires a further $500bn over the next decade in order to achieve its 2030 renewable energy target. This includes the capital cost of adding more than 300GW of new renewables infrastructure and the associated grid firming (batteries, hydro, blended gas peakers, and demand response management), grid transmission, distribution modernisation, and capacity expansions.

Wind-solar hybrid

Those are lofty indeed, but experts say, given India’s compulsion to move away from dirty fuel to clean energy sources, the country also needs to explore options, technologies and business models – aside from plain vanilla contracts –to expedite the adoption of increasing amounts of low-cost but intermittent renewable energy.

A hybrid model which harnesses both solar and wind energy could be a viable new renewable energy fit due to the high potential of both resources across various locations and the provision of enhanced grid stability and reliability, they add.

A joint study by JMK Research and IEEFA – Wind-Solar Hybrid: India’s Next Wave of Renewable Energy Growth – says that India’s long coastline is endowed with high-speed wind, as well as rich solar energy resources that “provides a great opportunity for the wind-solar hybrid industry to thrive.”

“Although wind and solar capacity can be operating at the same or in different locations, co-locating reduces costs related to land, grid connection, hardware and other installation overheads,” the report says.

With the potential of slicing the cost by 7% to 8% compared to a standalone solar system, both Gulia and Garg believe that wind-solar hybrid systems can “help the government boost renewable energy development” to meet its 2020 and 2030 targets, rather than “simply relying on standalone wind and solar”.

Government initiatives

Some initiatives by the Government of India to boost India’s renewable energy sector are as follows:

- In March 2021, the Union Cabinet approved a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in the field of renewable energy cooperation between India and the France.

- In March 2021, Haryana announced a scheme with a 40% subsidy for a 3 KW plant in homes, in accordance with the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy’s guidelines, to encourage solar energy in the state. For solar systems of 4-10 KW, a 20% subsidy would be available for installation from specified companies.

- In March 2021, India introduced Gram Ujala, an ambitious programme to include the world’s cheapest LED bulbs in rural areas for Rs. 10 (14 US cents), advancing its climate change policy and bolstering its self-reliance credentials.

- In the Union Budget 2021-22, the Ministry for New and Renewable Energy was allocated Rs. 5,753 crore ($788.45 million) and Rs. 300 crore ($41.12 million) for the ‘Green Energy Corridor’ scheme.

- In the Union Budget 2021-22, the government provided an additional capital infusion of Rs. 1,000 crore ($137 million) to Solar Energy Corp of India (SECI) and Rs. 1,500 crore ($205.57 million) to Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency.

- To encourage domestic production, customs duty on solar inverters has been increased from 5% to 20%, and on solar lanterns from 5% to 15%.

- In November 2020, Ladakh got the largest solar power project set-up under the central government’s ‘Make In India’ initiative at Leh Indian Air Force Station with a capacity of 1.5 MW.

- In November 2020, the government announced a production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme worth Rs. 4,500 crore ($610 million) for high-efficiency solar PV modules manufacturing over a five-year period.

- On November 17, Energy Efficiency Services Ltd (EESL), a joint venture of PSUs under the Ministry of Power and the Department of New & Renewable Energy (DNRE) in Goa, signed an MoU to discuss the rollout of India’s first Convergence Project in the state.

- In October 2020, the government announced a plan to set up an inter-ministerial committee under NITI Aayog to research and study energy modelling. This, along with a steering committee, will serve the India Energy Modelling Forum (IEMF), which was jointly launched by NITI Aayog and the US Agency for International Development.

- India plans to add 30 GW of renewable energy capacity along a desert on its western border such as Gujarat and Rajasthan.

- The Delhi Government decided to shut down a thermal power plant in Rajghat and develop it into 5 GW solar park.

- The Government of India has announced plans to implement a $238 million National Mission on advanced ultra-supercritical technologies for cleaner coal utilisation;

- Indian Railways is taking increased efforts through sustained energy efficient measures and maximum use of clean fuel to cut emissions by 33% by 2030.