Amid copious amounts of doom and gloom, climate summit COP29 kicked off this week with a rare bright spot: a decision that could jumpstart the creation of a global United Nations-backed carbon market.

The market — that could be up and running next year — is expected to bring integrity to a sector overshadowed by scandals and scepticism, plus channel urgent climate finance to developing economies, and provide funding for climate technologies and strategies.

But one question looms over the future of global carbon markets: How will the re-election of Donald Trump, who steadfastly believes a climate crisis doesn’t exist, affect their growth?

Also on AF: Elon Musk Said to Back Trump’s Plan to Kill Biden’s EV Tax Credit

The answer, as you may have guessed, is not straightforward.

Carbon industry experts that spoke to Asia Financial believe that while it may be too early to tell how Trump would approach carbon markets, the future is a mix of uncertainty and lots of hope.

Certainties and uncertainties

The United States is the world’s biggest historic emitter of planet-warming greenhouse gases. It is also the largest economy of the world, meaning it has both motive, and funds, to bolster the growth of carbon markets.

But Trump is on track to pull the US out of the Paris Agreement — which, under its Article 6, outlines the mechanism for global carbon trading.

Trump likely has “an executive order already drafted” to do so, according to Anna Karakitsos, a senior government affairs adviser at energy law firm Bracewell LLP.

Trump “views most climate initiatives as unnecessary regulations and wasteful government spending that stymie economic growth,” Karakitsos said.

The impact of that decision would only materialise by 2026, however.

“It will take 12 months for that notice of withdrawal to take effect, so it will be interesting to see whether the US sends any negotiators to COP30 in Brazil in November 2025, prior to the withdrawal being fully effected,” said Simon Puleston Jones, managing director of carbon market brokerage Emral Carbon.

He believes it is all but certain that Trump will pull the US out of the Paris Agreement.

The withdrawal would mean “US carbon project developers will be unable to participate in the carbon market” linked to the Paris Agreement “in relation to their US projects,” Jones said.

Trump is also likely to cut back spending under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) — enforced by the outgoing Joe Biden government.

That could mean fewer funds for clean energy, a rollback on tax credits for electric vehicle purchases and uncertainty around 45Q tax credits that — despite their criticisms — have been a game-changer for American firms working on carbon removal (CDR) technology Direct Air Capture (DAC).

But carbon markets are too big to fail

Considering the US has led innovation in Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), and DAC, Trump’s potential decisions will make the stability of carbon markets uncertain in the near-term.

“If he pulls back federal funding for clean energy… it will slow the expansion and credibility of VCMs in the US by limiting funding for high-quality carbon projects and weakening verification standards. And that absolutely will impact the supply of credits,” Bracewell’s Karakitsos said.

VCMs – voluntary carbon markets – are a largely unregulated mechanism that allow private firms, organisations, and individuals to buy and sell credits to manage their carbon footprint on a voluntary basis. They operate alongside compliance markets that are regulated and often formed by regional, national or international authorities.

The US does not currently have a national market, but some states such as California and Washington have set up regional compliance markets.

In his first term as president, Trump sued California’s carbon market but lost the challenge. And experts say that federal laws since have only strengthened such state-led markets.

That brings us to a crucial piece of the puzzle — carbon markets have now become too big to fail — even without official US participation.

According to LSEG, the value of global compliance carbon markets reached a record $949 billion in 2023. The European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) accounted for about 87% of that value and the price of carbon permits hit record highs in the EU ETS, in American state-led markets and also in China, which launched its ETS in 2021.

That poses important considerations for American firms that have overseas operations.

“Many US firms operate internationally and thus must comply with stricter regulations in regions like the EU. These firms are expected to maintain their commitment to carbon credits to meet sustainability goals and regulatory requirements,” said Clement Gourrierec, founder of CrystalTrade, a French green tech firm that makes software for measuring the effectiveness of carbon removal projects.

That “will keep demand [for carbon credits] strong and help shape global market dynamics,” Gourrierec added.

US climate firms with overseas projects will also be able to continue to supply carbon credits to regional and international markets, such as the UN-backed one, Emral Carbon’s Jones noted.

It is worth noting that prices on global ETS markets were little affected by Trump’s re-election or in the following days when he began picking out his administration.

It’s all about climate and politics

Meanwhile, growing interest in carbon dioxide removal across Africa, South America, and Asia also means credits for methods like biochar (a charcoal-like substance produced from burning biomass in the absence of oxygen), have “a wide buyer base beyond the US,” CrystalTrade’s Gourrierec noted.

“International players are well-positioned to fill any gaps [created by the US], ensuring continued progress in the carbon markets globally,” he added.

In essence, while Trump’s return to power in the US creates some risk in the medium-term, growing climate awareness will keep propelling carbon markets over the longer-term.

“Regardless of the election result, a transition to a low-carbon economy is already underway and the shift to net zero remains of utmost importance to economic and social prosperity,” carbon asset developer and climate consultancy South Pole said in a statement.

The firm said it hopes “the results of the election will encourage other countries, states, and companies to double down on their net zero commitments.”

That said, there may even be significant political value for Trump in bolstering carbon markets, particularly VCMs.

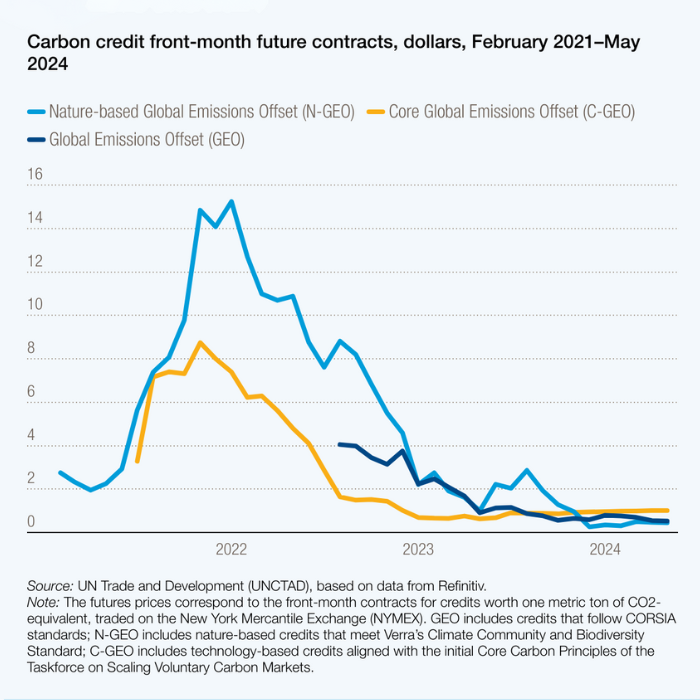

Compared to their compliance-based counterparts, voluntary carbon markets were worth a much smaller $723 million last year. That was after their value plummeted from $2 billion in 2022, due to repeated greenwashing scandals.

The Biden administration this year took an array of decisions to endorse VCMs and improve their oversight. And Trump might benefit from keeping that up.

For instance, one of Trump’s closest current aides — Elon Musk — has seen significant earnings from carbon credits. Musk’s EV firm Tesla earned a record $1.79 billion from carbon credit sales last year, according to annual reports.

“It seems unlikely that the new administration would choose to cut off Tesla’s access to revenue via the sale of such credits,” Emral Carbon’s Jones said, on why Trump was unlikely to ban VCMs.

Trump’s criticism of China, since his first term, and threat to impose 60% tariffs on imports from the country also offers some hope.

Getting “a leg up against China” could motivate Trump to strengthen US participation in VCM’s, Bracewell’s Karakitsos noted.

“He could influence global trade practices by leveraging [VCMs] in international trade negotiations and integrate carbon-related trade mechanisms or standards with major trade partners like the EU, who are also tightening their carbon standards,” she said.

“The US does not operate in a vacuum, and what our trade partners are doing does matter.”

The future is integrity

What these factors largely mean is that the real growth of carbon markets over the long-term will depend on the integrity of the credits they trade, regardless of Trump’s stance on climate.

VCMs have faced issues like greenwashing, inaccurate emissions reporting and scams even without US participation. And large-scale efforts are being made to improve their accountability and oversight across the globe.

This week’s breakthrough COP29 consensus on new standards for international carbon trading, is one big example. It signals “a commitment to move forward and get capital moving,” Guy Turner, head of MSCI carbon markets, said in a press statement.

Organisations like The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) have sought to address concerns around credits by launching Core Carbon Principle (CCP) standards. Current projects with methodologies approved under those standards have the potential to issue more than 400 million carbon credits, the organisation has said.

Meanwhile, Microsoft, the world’s largest buyer of CDR credits is also backing an effort to bring standardisation to the carbon removal industry.

With greater reliability, VCMs could reach a value of $250 billion a year by 2030 and $1.5 trillion a year by 2050, according to Barclays.

But will Trump find the motivation to help those efforts? That is a question the world might find itself asking once he re-enters the White House in January.

- Vishakha Saxena

Also read:

Fossil Fuels Set to Drive Global Emissions to a Record, Yet Again

Climate Startup Raises $32m to Bury Carbon Waste in Wells

‘We Are on a Road to Ruin’: COP29 Kicks Off Amid Trump Worry

Uncertainty on Methane Emission Fee as Biden Term Nears End

Scientists Say 2024 ‘Virtually Certain’ to be Hottest on Record

Floods or Drought: Climate Change Worsens Global Water Woes

Asian Economies at Risk From Inaction on Climate Change: ADB

Climate Change Has Cost China $32 Billion in Just One Quarter

Emissions of World’s Super Rich ‘Drive Economic Losses, Deaths’

Energy Emissions Set to Peak But ‘Not in Time’ For Climate Goals

BP Dumps Oil Pledge While Chasing Billions in Climate Subsidies

Scientists Fear Nature’s Carbon Sinks Are Failing – Guardian

Could Melting Glaciers Trigger Volcanic Eruptions? – Reuters