(ATF) A vital part of the role credit rating agencies play in today’s complex financial markets entails differentiating between various borrowers, a key consideration in pricing of their bonds.

This is particularly relevant for China which is accelerating reforms and increasingly opening up its financial services sector at a time when demand for Chinese credits is rising.

At a pivotal time like this, the lack of granularity and global comparability of the incumbent ratings could be a significant challenge and obstacle for international investors.

Currently all local government bonds issued in China are rated AAA of “national scale ratings”, so a rating differentiation is lacking.

At Pengyuan International, we assign credit ratings to the Chinese local governments with reasonable differentiations. We started the effort two years ago – and that’s also when we started to build our Chinese local governments database.

NO SECRET SAUCE

So far, we have rated 20 local governments out of 31 mainland provinces with hope to cover all provinces by the end of this year. There is no secret sauce in what we do, and our rating methodology is transparent and according to conventions well understood in the global markets.

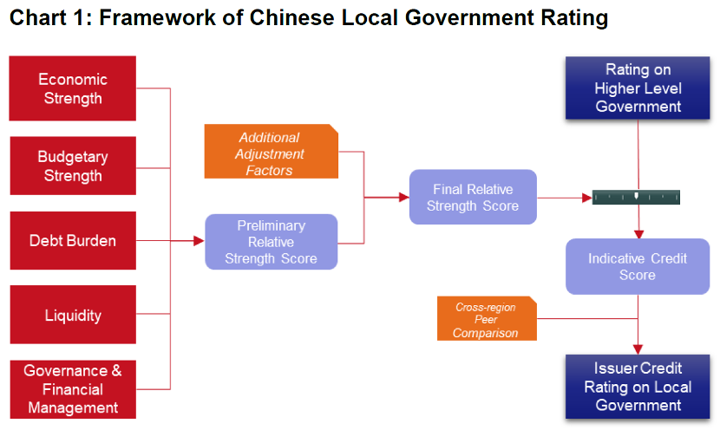

The following chart illustrates how we arrive at the final rating of a Chinese local government. Both qualitative and quantitative elements are involved in assigning a credit rating, four out of five assessments to arrive at the Preliminary Relative Strength Score are quantitative: Economic Strength, Budgetary Strength, Debt Burden and Liquidity.

So, in this sense, our local government ratings are quite data-driven and transparent.

Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs), a much sought-after asset class amongst Chinese credit bond investors, are also the most misunderstood and therefore are worth analysing from a fixed income perspective.

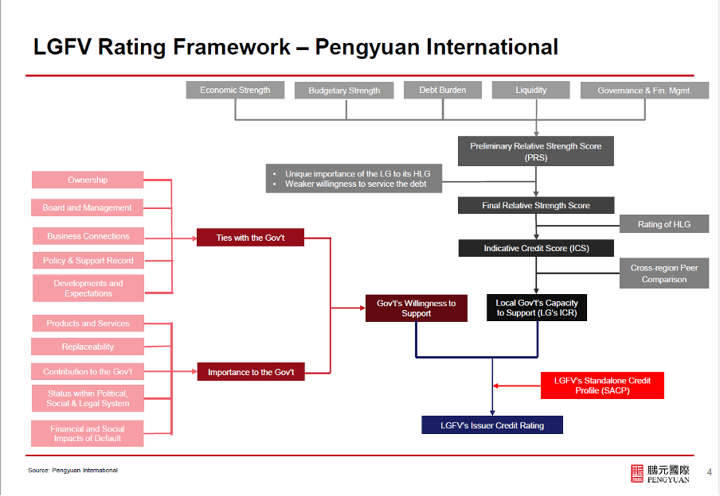

While the word “government” appears in the name, it is important to understand that these LGFVs are not risk-free. In essence, there are three key elements in our assessment of LGFVs.

The first is the standalone credit profile, as LGFVs are typically an extension of government function and not operating for profit, the standalone credit profile is limited (we often see them in single “b” category in our assessment). Then we assess both the government’s capability to support and its willingness to support. The three pieces of information will give us a final credit rating of an LGFV.

The chart below illustrates our LGFV rating framework.

None of the publicly issued LGFV bonds have defaulted so far, and LGFVs remain as popular in the credit markets. As a credit rating agency we closely monitor the development of LGFV credits, keeping the LGFV rating approach validated and the market abreast of our views.

Indeed, the latest string of defaults have raised worries about the growing pile of debt in China’s LGFVs – where total assets have surged 40% in the past four years while revenues and net income, have inched up just 6% and 4% respectively.

But we do not see the recent spike in defaults triggering a systemic problem. China has plenty of tools in the kit to maintain financial market and social stability even if defaults rise. We see defaults continuing to rise in China, driven by both the tightening credit conditions and the higher-level tolerance towards defaults from the government side.

As a result of this change, there is a stronger demand for high-quality credit ratings/analysis, as well as a more market-oriented pricing. All these factors bode well for China’s financial market in the long term despite the short-term pain.

We project the debt level of local governments in general will increase mildly in 2021 with greater disparities. Gaps will be further widened among local government’s debt level due to their uneven impact by the pandemic and various extents of fiscal stimulus.

MODEST IMPACT

China’s containment of the coronavirus pandemic, coupled with the unconventional fiscal stimulus, meant its economy recovered rapidly, with more than half of provinces reporting gross domestic product (GDP) growth above 3% in 2020. Although confirmed cases increased marginally at the start of 2021, the impact should be modest with the government’s strict controls in place. In our sovereign rating report published in September 2020, we forecast China’s growth to be above 8% for 2021.

With better-than-expected economic performance, we believe that China’s government will gradually withdraw the coronavirus stimulus and refocus on deleveraging. In addition, the proceeds from the local government special bonds issued last year have not been spent fully and effectively.

In contrast with the past two years, Beijing is not so keen on encouraging local governments selling their bonds in times of market uncertainty, due to recent bond defaults by China’s state-owned enterprises. We expect the quota for the local government special bonds will be announced at the National People’s Congress in March and the amount is likely to drop slightly to 3.5 trillion yuan ($540 billion) from 3.75 trillion yuan in 2020.

All these point to signs of a maturing bond market with the better understanding of credits paving for greater credit differentiation and steepening credit curve. In the long run China should see a better allocation of resources as a result of greater sophistication in its fixed income markets.

Terry Zhang is Head of Global Strategy and Business Management at Pengyuan International