GAM Investments’ Mark Hawtin and the Disruptive Growth team examine the buying frenzy around Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) and discuss why they believe de-SPAC transactions could provide investment opportunities over the next few years.

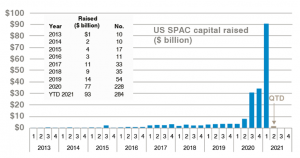

(AF) The first quarter of 2021 saw the SPAC market reach a frenzied peak in the US, with issuance in the first quarter matching the whole of 2020 (see Chart 1 below). SPACs have been around since the early 2000s. The first SPAC, Millstream Acquisition Corporation, launched its initial public offering (IPO) in 2003.

Some 18 years later, with markets riding high, it is not surprising that some have branded SPACs as a mania. History is littered with manic episodes or ‘bubbles’ that went badly wrong. For example, all sorts of real and imaginary investments were touted during the South Sea Bubble in the early 1700s. In this case, one company was floated to buy the Irish bogs, another to manufacture a gun to fire square cannon balls and one company was formed “for carrying-on an undertaking of great advantage but no-one to know what it is!” Remarkably, some 2,000 pounds – the equivalent of about 400,000 pounds today – was invested in this venture at the time.

SPACs raise money with no direct business plan, only the intention to acquire an as-yet-unidentified business in a particular sector. Indeed, in the US, it is illegal to approach a possible target company ahead of the listing of a SPAC.

But this is where the lack of visibility ends – in fact, for investors in the original SPAC IPO, the risk is often limited and has hence drawn significant bond-like investors hungry for stronger returns. Once the SPAC is launched, it has 24 months to find an acquisition target to merge with or to de-SPAC. If it fails to do so, the SPAC is disbanded, and the capital returned to investors.

Chart 1: SPAC IPO volumes continued to surge in early 2021

Source: Dealogic, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. Data as of 26 February 2021. For illustrative purposes only.

SPACs face lower levels of scrutiny than IPOs and the hurdles for companies to comply with listing requirements are lower, so it has become a popular route to market for earlier stage companies. This, of course, brings with it concerns about suitability for investors in the public market and we expect regulation will be tightened in this area.

However, at the core, this is a sensible way to bring companies to the market and it has the big advantage of avoiding the big first day IPO price moves; the pricing is set in the merger terms.

The real issue with SPACs, which occurred in Q1 2021, in particular, are buying frenzies on the SPAC-listed vehicle that in some cases drove the share prices up multi-fold without any identified target.

For example, just advertising that a SPAC was looking to merge with a company in the electric vehicle space might lead to such a move higher. SPACs are issued at $10 per share in the US and by the time the sponsor carry is taken into account, the true cash per share is closer to $8-$8.50. At the point of listing, that is all the tangible value the SPAC has. It may have a highly regarded management team, in some cases, it may have attracted some high-profile celebrities as investors, but the tangible book is less than $10 per share.

It is our contention that there will be many interesting de-SPAC deals that could yield attractive investment opportunities.

However, we believe is critical to wait until the merger candidate has been identified and made public, maybe even waiting for the deal to be consummated, at which time an investor is buying a tangible business proposition that can be valued by traditional metrics.

In fact, de-SPACs may provide investment opportunities over the next three to five years as under-researched merged entities create an environment reminiscent of the art of stock picking in the 1980s when legendary investors, like Peter Lynch and Warren Buffett, were finding hidden gems capable of yielding magic multi-bagger returns.

ALSO SEE: