Europe’s biggest utilities Enel and Iberdrola saw the clean energy transition coming decades ago when others baulked at the high cost of producing energy from the sun and wind and instead stuck with coal and oil.

Thanks to early decisions to buy power grids and build renewable plants, the once-staid utilities are now among a handful of global green energy majors going into battle with Big Oil to supply low-carbon power full of confidence.

European oil giants such as BP, Royal Dutch Shell and Total have sharpened their focus on power, seeing it as the sector to build their businesses around as they reinvent themselves as clean energy suppliers.

But they will need to wrestle market share from incumbents such as Enel and Iberdrola that have been positioning themselves for years to profit from the shift to cleaner energy, betting the demise of fossil fuels was inevitable.

“The energy transition has been part of my life,” Enel chief executive Francesco Starace said. “There was no eureka moment for us. We just said this is too stupid to be continued for a long time.”

The transformation of the two companies into global green powerhouses has helped boost their profits and share prices while generating cash and dividends despite a global pandemic. Over the last two years their shares have skyrocketed as investors shifted from oil stocks to buy into businesses they felt had the financial footing and skill sets to lead the accelerating energy transition.

Enel and Iberdrola have built clean energy capacity in key markets such as the United States and Latin America and are now aiming to have a combined 215 gigawatts of their own renewable capacity by 2030 – enough to power some 150 million European homes, based on an estimate by consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

Other leading green utilities that have also benefited from the shift away from fossil fuels include wind and solar power giant NextEra Energy in the United states and Denmark’s offshore wind farm specialist Orsted.

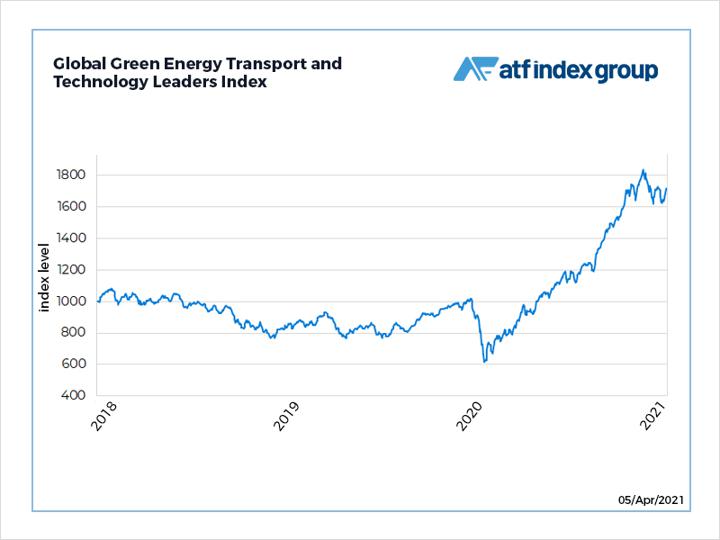

The Global Green Energy Transport and Technology Leaders Index created by Asia Times Financial in collaboration with ALLINDEX, is a benchmark that tracks shares of leaders in electric vehicle and renewable energy production and storage businesses.

General manager and CEO of Enel Group Francesco Starace attends a media event in Milan in January 2018. File photo by Alessandro Garofalo/Reuters.

‘THIS IS NOT THE FIRST ENERGY TRANSITION’

Even before joining Enel at the turn of the century, Starace was pushing companies hooked on oil and coal to switch to less-polluting gas turbines.

“This is not the first energy transition, before there were coal steam cycles which then transitioned to gas steam and so on,” he said. “I liked the sustainable side of renewables, the fact you keep reusing the same energy from the sun.”

The turning point for Enel was its creation of Enel Green Power (EGP) in 2008, just after it launched a 39 billion euro takeover of Spain’s Endesa, a deal that boosted its access to Latin America’s fast-growing markets. Starace was tasked with running EGP as a viable independent business which did not rely on the generous incentives governments were offering then to kick-start their green drives.

“Renewables were a whole different ball game – smaller plants, less competitive, costlier. It needed its own space with the right footprint and technology mix to deliver,” a source who worked at EGP said. By the time Starace became chief executive of the Enel group in 2014, he lost little time in buying back the part of EGP listed in 2010 so the growth engine was fully in-house.

Iberdrola chief executive Ignacio Galan, seen above, made an even earlier switch away from coal and oil when he took the helm at Spain’s largest private utility in 2001.

He started closing fuel oil power plants – 3.2 gigawatts (GW) of capacity had been decommissioned by 2012 – and shut the company’s last two coal-fired plants in 2020.

At the same time, Iberdrola boosted its spending on building renewable plants, mainly wind farms, in Spain from 352 million euros ($413 million)in 2001 to over 1 billion euros in 2004.

Galan met with internal and regulatory resistance, though Swiss bank UBS said in a 2002 report entitled “Kiss the Frog” that Iberdrola’s new low-carbon focus could produce profits.

Investors still needed convincing. One Iberdrola source recalled a US asset manager’s doubts about wind farms in 2004, calling them pretty white darts stuck on a hillside. He changed his mind when he visited one in Spain in 2007.

“He was sceptical, but three years later he said we were right,” the source said.

GRIDS APART

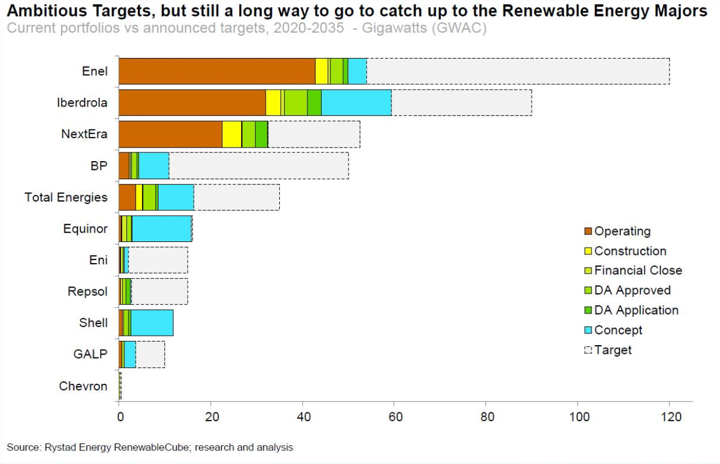

Consultancy Rystad Energy says oil giants have a long way to catch up with the renewable energy majors in terms of capacity, despite their ambitious target. By 2035, it estimates Enel will still be leading followed by Iberdrola and NextEra.

Enel and Iberdrola have another significant advantage that analysts say oil majors will struggle to match – thriving power grids businesses. Almost half of Enel and Iberdrola’s earnings come from millions of kilometres of power lines carrying electricity into homes in Europe, the United States and Latin America.

“Grids are the backbone of the energy transition,” says Javier Suarez, head of the utility desk at Milan’s Mediobanca. “Owning them means steady cash flow and lower investment risk.”

Most grids are monopolies with regulated, guaranteed returns and operators rarely put them up for sale.

“Any new entrant into the industry is not going to be able to get access easily or certainly not cheaply to the really good legacy assets that Iberdrola and Enel have – the infrastructure assets,” said Wood Mackenzie analyst Tom Heggarty.

Networks built to take one-way power flows from fossil-fuel plants now need a massive round of investment to accommodate electricity generation from sources such as rooftop solar panels that can also inject power back into the grid.

Incumbents like Enel and Iberdrola are the most likely candidates to provide capital, analysts say.

Because returns are typically locked in with contracts, more spending on grids and renewable power generation assets will translate into more profit for the major green utilities, said Goldman Sachs. By the US bank’s calculations, reaching international targets to cut carbon emissions to net zero by 2050 will require a 200% jump in spending on such power infrastructure.

Enel is now looking to expand its grid network in Europe, Latin America, the United States and the Asia Pacific region, sources said.

In November, it said it would spend 150 billion euros of its own money to help cut its carbon emissions 80% by 2030 and nearly triple its owned renewables capacity to 120 GW, with grids soaking up almost half the overall investment.

Iberdrola, meanwhile, has earmarked more than a third of its spending plans for grids, mostly in the United States, which will become its biggest market for regulated assets.

It has pledged to spend 150 billion euros on tripling its renewable capacity and doubling its network assets by 2030. The sums dwarf amounts European oil majors have pledged for their fledgling green businesses so far.

“I don’t think it was simple to decide to spend money in renewables,” Pierre Bourderye of PJT Partners said of Enel and Iberdrola. “If it had been simple others would have done it at the same time, but they did it 10 years later.”

Reporting by Reuters