HOUSTON: Badly-timed bets on rising demand have Exxon Mobil Corp facing a shortfall of about $48 billion through 2021, according to a Reuters tally and Wall Street estimates – a situation that will require the top US oil company to make deep cuts to its staff and projects.

Wall Street investors are even starting to worry about the once-sacrosanct dividend at Exxon, which in the 20th Century became the world’s most valuable company using global scale, relentless expansion and strict financial controls.

Exxon weathered a series of setbacks last decade and under Chief Executive Darren Woods sought to return to past prominence by big bets on US shale oilfields, pipelines and global refining and plastics. It also bet big on offshore Guyana, where it discovered up to 8 billion barrels of oil, six years of production at its current rate.

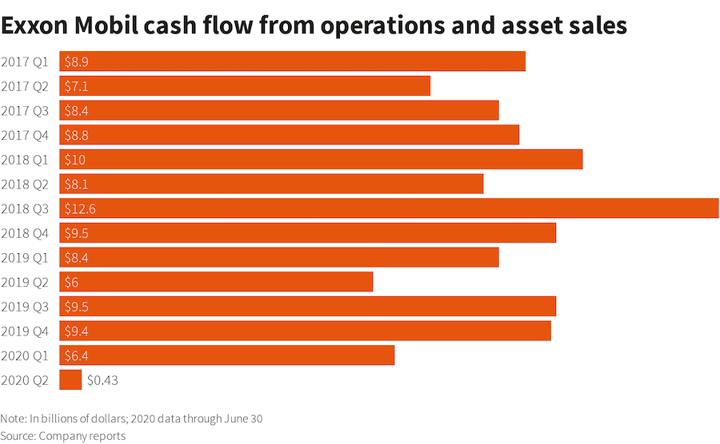

But Exxon’s ability to finance that global expansion is no longer assured. This year the company borrowed $23 billion to pay its bills, nearly doubling its outstanding debt. In July, it posted its first back-to-back quarterly losses ever. It faces a full-year $1.86 billion loss, according to Refinitiv, excluding asset sales or write downs.

The looming shortfall of about $48 billion through 2021 was calculated using cash from operations, commitments to shareholder payouts and costs for the massive expansion program Exxon had planned. Now the company is embarking on a worldwide review of where it can cut expenses, and analysts believe the once unthinkable dividend cut has grown more likely.

Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods speaks at the Russian Energy Week forum in Moscow in October 2019. Iliya Pitalev / Sputnik via AFP.

JOB REVIEWS, BENEFIT CUTS

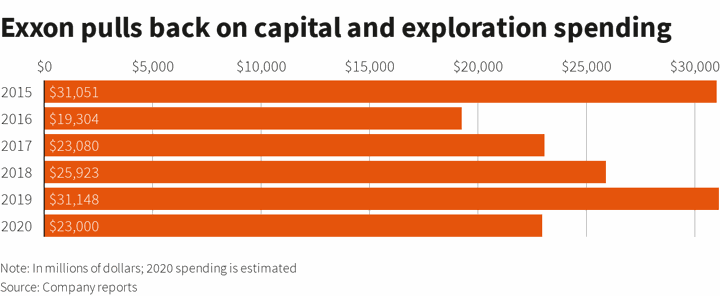

This year’s sharp drop in oil demand and pricing has shredded Woods’ plan to spend at least $30 billion a year through 2025 to revive production and earnings by expanding in oil processing, chemicals and production, and by taking a commanding role in US shale and liquefied natural gas, markets that then looked promising.

Instead, he must prepare Exxon to operate in a world of weaker demand for its oil, gas and plastics. The company has been dropped from the Dow Jones index of top US industrial companies after 92 years. It is exposing up to 10% of US staff to harsh reviews that could push thousands out of the company, and is taking away lavish retirement benefits that had career employees staying 30 years on average.

Exxon declined to make an executive available for an interview, and a spokesman said details of cost cuts would be disclosed early next year.

“We remain committed to our capital allocation priorities – investing in industry advantaged projects, paying a reliable and growing dividend, and maintaining a strong balance sheet,” spokesman Casey Norton said.

A review of projects now underway aims to “maximize efficiency and capture additional cost savings to put us in the strongest position” as energy markets improve, he said.

Oil prices have dropped 35% from the start of 2020 as demand collapsed during the Covid-19 pandemic. BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Total and Repsol and others have cut billions of dollars off the value of their oil and gas properties, something Exxon has yet to do.

European majors also are adding renewable energy and electricity to their portfolios, a hedge against permanently reduced oil and gas demand. BP plans by 2030 to reduce its fossil fuel production by 40%. It plans to sell even more fossil fuel properties if oil prices have a sustained rally.

DEBT NEARLY DOUBLES

Exxon’s cash from operations – estimated to be about $17.4 billion this year – is $20 billion below the funds needed for this year’s already pared investment plan and shareholder dividend, a Reuters analysis showed.

The company’s stock price closed Friday at $39.08, off 56% since Woods became CEO. He raised $23.19 billion in new debt this year to bolster finances, but has vowed not to borrow more and as recently as July insisted the dividend was sacrosanct.

Investors say the commitments will be difficult to keep. “At $41 or $42 [per barrel] crude, you can’t put those puzzle pieces together and have them make sense,” said Mark Stoeckle, senior portfolio manager at Adams Funds, which holds about $70 million in Exxon shares.

Exxon must cut its dividend if the share price remains depressed, Stoeckle said. “Something has to give. Wherever the give comes hurts management credibility,” he said.

A cut would be “cataclysmic” for Exxon’s stock, said equity analyst Paul Sankey of Sankey Research, given that executives in July reiterated its importance.

Exxon’s weak cash flow worries investors that hold the stock for its nearly 9% dividend. Matrix Asset Advisors has it on a “watch list in terms of our conviction and their ability to defend and grow the dividend,” said David Katz, chief investment officer at the New York firm.

SPENDING CUTS AND DEFERRALS

Exxon will slash spending in the Permian Basin shale field this year to about $3 billion from an original $7.4 billion budget, consultancy Rystad Energy estimates.

The company has said it plans to reduce the number of drilling rigs there to 15 or fewer, from 55 early this year, and the company’s pullback “will continue,” senior vice president Neil Chapman said in a July call. Spending on refining and chemicals plants that take years to design and complete, “is really a question of deferral,” he added.

A $10-billion chemical plant in China remains subject to permits, the Exxon spokesman said. Spending limits will further constrain its oil, refining and plastics businesses and could revive pressure on the company to divest some operations.

“Each of our core businesses could be a powerhouse in its own right,” Woods said when he rolled out the vision in early 2017. At the time, he was pushing back at calls to spin off businesses to boost lagging returns.

Woods stuck to the growth targets last year, putting this year’s potential earnings at $25.1 billion with oil at $60 a barrel and assuming flat refining and chemical margins. That forecast included 2020 cash flow and asset sales targets that have become unreachable since the pandemic hit.

Analysts said that Woods must dial back. Project outlays next year could drop to between $10.4 billion and $15 billion, according to ScotiaBank and RBC Capital Markets, half the original outlook.

NO URGENCY FOR LNG

Some project schedules are being quietly stretched to save costs.

Construction at a $10 billion-plus LNG facility in Texas where Exxon holds a 30% stake already was moving slowly and now “there isn’t the urgency,” said Alex Munton, with consulting and data firm Wood Mackenzie. He expects its startup will be delayed a year, to 2025 at the earliest.

A massive LNG project in Mozambique likely will not get a final investment decision until 2023, as an expansion of Exxon LNG exports in Papua, New Guinea, is delayed by government talks and low LNG prices, Munton said.

“The reality is that Exxon is not moving forward with either of those in the near term,” Munton said.

In Mexico, Exxon will likely cut offshore activity after its first well was not commercial, according to people familiar with its operations. It will instead focus on fuel imports and retail sales, they said.

Exxon has begun exploration drilling in Brazil, where the company returned in 2017 to become second only to state-controlled Petroleo Brasileiro SA in holdings of offshore exploration acreage. But “spend and activity deferrals cannot be ruled out as part of any cost-cutting,” said Ruaraidh Montgomery, director at Welligence Energy Analytics.

Other projects already begun, including the $1.9 billion expansion of its Beaumont, Texas, refinery, face an up to one year postponement.

Exxon declined to comment on the LNG, Mexico or Brazil spending.

Other than Guyana, “there will be no other sacred cow in the near-term budget,” analyst Paul Cheng of ScotiaBank said.

(Reporting by Jennifer Hiller in Houston and Marianna Parraga in Mexico City; editing by Gary McWilliams, David Gaffen and David Gregorio)