With no job or savings, Indian electrician Shibhu Clemance had hoped to return to work in Kuwait – until he learned of a proposal to drastically cut back on migrants in the country.

The 38-year-old, who lost his job in February due to the coronavirus pandemic, is among more than a million Indians in Kuwait, the largest expat group in the Gulf country of 4.4 million.

But after the coronavirus hit oil prices and local jobs, the country is considering new limits that could force about 800,000 to leave and slash their remittances – a crucial lifeline for families back home.

The proposal is in a new bill that would cut the total number of migrant workers in the country by 40% and require that the number of Indians should not exceed 15% of the Kuwaiti population.

“I came to the Gulf and toiled hard to provide a better life for my children. The Covid-19 crisis and now the new Kuwait law have shattered my dreams,” Clemance told the Thomson Reuters Foundation by phone from the coastal city of Mangaf.

Before he lost his job in February, he sent 40,000 Indian rupees ($530) to his wife and two children who live in a cramped house in the southern Indian state of Kerala with his in-laws and six other relatives.

Without a home of his own in Kerala and with little hope of finding work in a state that has been receiving India’s largest influx of returning migrants, Clemance fears going back to his family.

The government has yet to approve the bill, but the prime minister said last month he wants to cut the expat population of about 3 million.

Assembly Speaker Marzouq Al-Ghanem has proposed a gradual reduction in foreign workers, starting with a 5% cut in numbers and indicated the country needed fewer low-skilled migrants.

Parliament will finalise the bill before the current session ends in October, before sending it to the government for approval.

‘Can’t even sleep’

Indians working in Kuwait sent home almost $4.6 billion in 2017, about 6.7% of total remittances to the country that year, according to World Bank data.

But a global recession in the wake of Covid-19 has decimated jobs and slashed cash flows. The World Bank estimates remittances to India will drop by 23% from $83 billion last year to $64 billion this year.

For Litty Shibhu, Clemance’s wife, managing the household and taking care of her large family without the monthly transfer from Kuwait has been tough.

“We are in real trouble since the money stopped coming … Every day Shibu calls me and shares his sorrows. I’m planning to sell my gold to help him,” the 29-year-old said.

“We will virtually be on the street if my husband is compelled to return. I can’t even sleep thinking about this.”

Her concerns are echoed throughout the southern state of Kerala, which has the largest number of people working in the Gulf at about two million, according to a 2018 migration survey by the Centre for Development Studies.

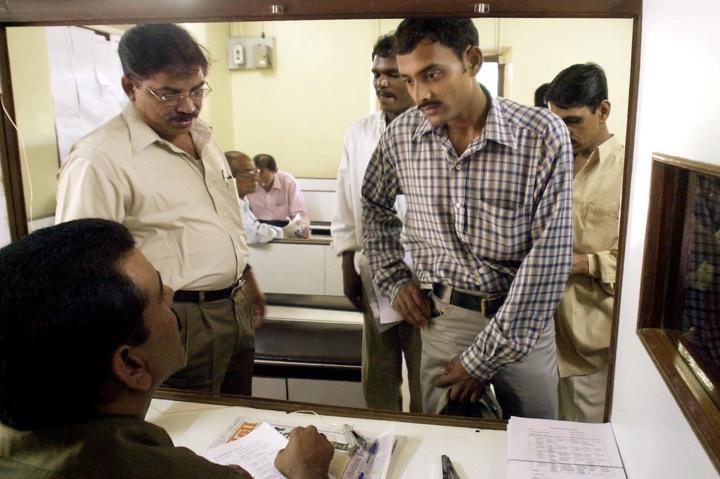

Indians queue in a recruitment office in Bombay to try to get jobs in the Gulf. File photo by AFP.

Kerala could be hit hard

State data shows 70% of the Indians in Kuwait are from Kerala. Remittances from the Gulf have been the backbone of Kerala’s economy since the 1960s, making up nearly 20% of the state’s gross domestic product, according to the survey.

If Kuwait passes the bill, it could further overwhelm Kerala at a time when it has been scrambling to reintegrate nearly half a million people returning from overseas and other Indian states, migration experts say.

S. Irudaya Rajan, a member of the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs’ research unit on international migration, said the expat bill was a knee-jerk reaction that would fizzle out after the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Even if Kuwait means business it will not have a huge impact on expatriates since most of them concentrate on the 3D jobs – dirty, dangerous and demeaning,” he said.

“These are categories that local nationals are unlikely to step in and take.”

A spokesman for India’s foreign ministry said it was monitoring developments in Kuwait and the foreign ministers of both countries had discussed the bill.

Robert Mogielnicki, resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington DC, said the impact on remittances would depend on when and how Kuwait enforces the expat quota.

“We’re talking about a tremendous demographic transformation. What is clear is that that’s not going to happen overnight,” he said.

He said Kuwait had historically been slow to enact economic reforms, but the current pressures had brought a sense of urgency.

Last month, the Indian government created a database of the skills and experience of returning migrants to help fill jobs in Indian and foreign companies.

Kerala has already devised a plan for the reintegration of incomers, said Harikrishnan Nampoothiri, chief of NORKA-Roots, a state government agency for the welfare of expats and returnees.

It includes upgrading skills to help people migrate again in the future, a financial scheme of up to 3 million rupees ($40,000) so they can start their own businesses, subsidised loans and mentoring camps.

Yet Vinoy Wilson, a father of three who works as a department store supervisor in Kuwait, had little hope of finding a job in India that would pay enough to fund his children’s education and repay the money he borrowed for a new home in Kerala.

Although his salary was slashed by 25% a few months ago, the 40-year-old said it was still enough to cover monthly expenses and send money back home to his mother-in-law.

He said he worried that he would be among the first low-skilled workers to be packed off, meaning he would have to sell his “dream” home.

“I don’t know where I will go if I lose my job. I have loans that I can’t repay without a steady income,” he said.

This story was published by the Thomson Reuters Foundation