The crisis at property giant China Evergrande Group poses a $305-billion conundrum for President Xi Jinping: how to impose financial discipline without fuelling social unrest.

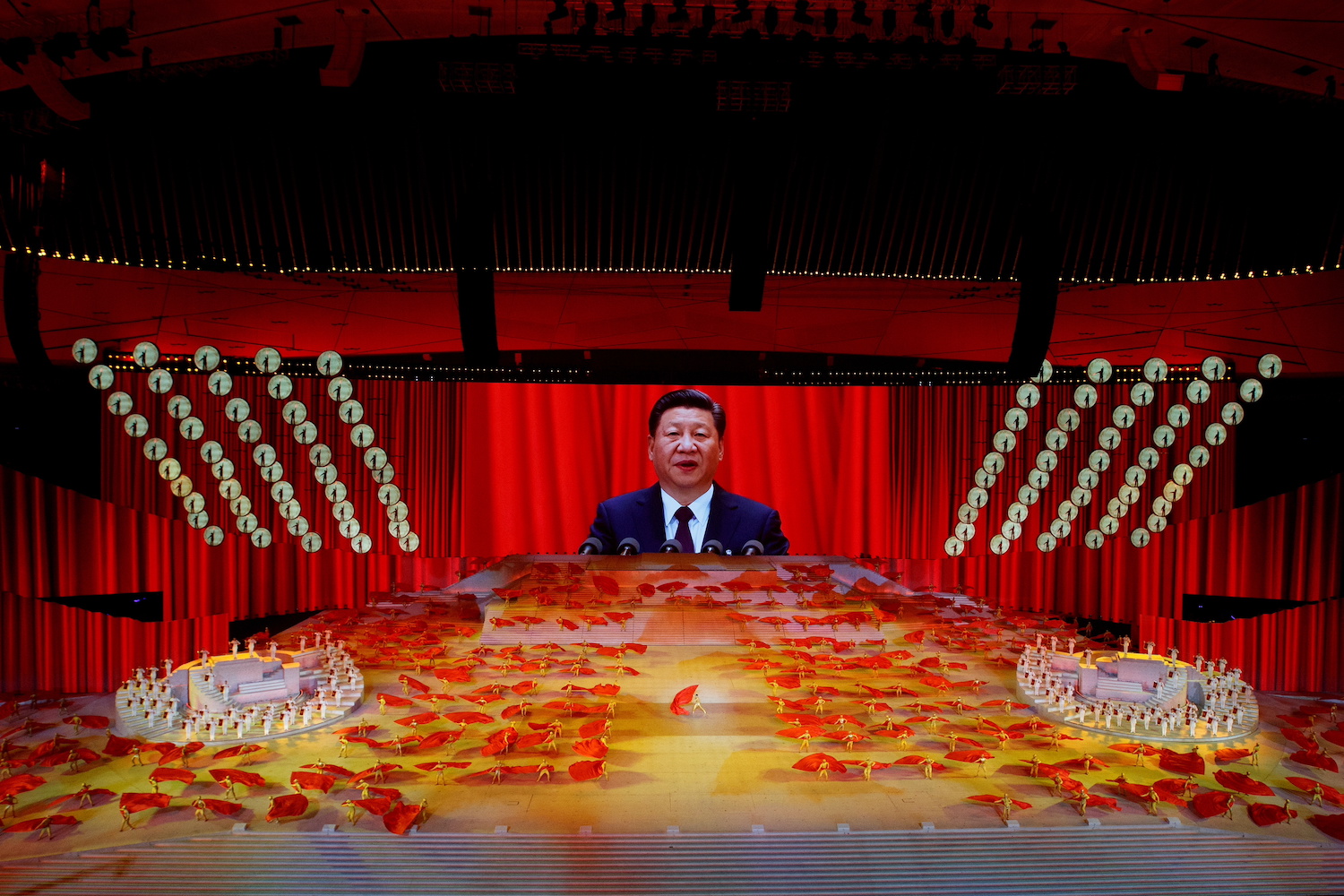

With one year before the Chinese president is poised to secure an unprecedented third five-year term, the stakes are high during what is proving to be the most consequential period of his tenure.

Evergrande’s borrow-to-build model was enabled by a government reliant on property sales for revenue and unwilling to bite the bullet on runaway indebtedness for fear a collapse in prices would have devastating consequences for a country in which property accounts for 40% of household wealth, analysts, academics and economists say.

Xi, who has unleashed a spate of industry and societal reforms this year in the name of “common prosperity”, has made clear that the excesses of decades of breakneck growth powered by a relentless rise in property prices and debt must be brought to heel.

GOVERNMENT CULPABLE

But shared responsibility for Evergrande’s crisis – and worries about the repercussions of a messy collapse – complicate decisions on the fate of a conglomerate with such massive debt that is scrambling to pay creditors, including bondholders owed $83 million in a coupon payment that was due on Thursday.

“The government has to some degree caused the problems at Evergrande,” said Andrew Collier, managing director at Orient Capital Research, citing debt ratio caps, known as the “three red lines”, placed on developers in 2020 that put Evergrande under significant stress and forced it to start to sell assets.

Those caps followed renewed official concern last year over property sector froth after monetary easing to cushion the impact of Covid-19 drove surging sales and signs of speculative overbuilding by developers.

But clamping down on property prices is difficult given the fiscal dependence on the sector. Local governments, which Orient Capital estimates account for 89% of total government spending, derived more than 40% of revenues from land sales in 2020, driving a codependent relationship with developers.

“(Developers) seem to get caught up in the political economy … which effectively leads to a tremendous number of bad decisions because you’re now making investments based on political whim and political winds, rather than actual sound business sense,” Fraser Howie, the author of several books about China’s financial system, said.

China’s State Council Information Office did not immediately reply to a faxed request for comment.

DEEP ROOTS

The roots of the crisis date to tax reforms in 1994, which bolstered central government coffers but left local governments reliant on land financing for revenue, Alfred Wu, an associate professor at Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore, said.

That triggered a rise in property prices and the growth of developers like Evergrande, which thrived in third- and fourth-tier cities.

“Evergrande is a cash cow for regional governments. If the company goes bust, the model of land-financing and regional governments will go bust, too. The central government won’t allow that,” Wu said.

Despite years of warnings from some quarters about the business model used by Evergrande and others, which has included taking on heavy debt to spur land and project acquisitions, the company was hardly a rogue operator.

Chairman and majority shareholder Hui Ka Yan took pains to show off his close alliance with Beijing and the ruling Communist Party, and was reciprocated.

Included in a list of Hui’s achievements in Evergrande’s 2020 annual report are being named a “national model worker”, an award-winning poverty fighter and an “Excellent Builder for the Socialist Cause with Chinese Characteristics”.

GREAT AWAKENING

Stability-obsessed Beijing is well aware that the rise in the housing market created not only great wealth but deep inequality.

One portfolio manager based outside China, who declined to be identified, said the 2019 anti-government protests in Hong Kong, blamed partly on inequality fuelled by sky-high housing costs, were a wake-up call for Beijing.

This year, Xi has set out to reform the “three huge mountains” of housing, education and healthcare to rein in soaring costs for city dwellers as a way to shore up legitimacy as the “people’s leader”, analysts said.

Protests by disgruntled suppliers, home buyers and investors last week illustrated discontent that could spiral in the event a default sparks crises at other developers.

UBS estimated there are 10 developers with potentially risky positions accounting for combined contract sales of 1.86 trillion yuan ($287.92 billion), nearly three times Evergrande’s total.

Still, many analysts say a wider crisis is unlikely, predicting that authorities would choose a route of squeezing the overall property sector while addressing individual problems as they arise.

“The government knows that if it doesn’t handle Evergrande carefully and lets it go bankrupt, disgruntled homeowners and shareholders could cause social instability, loan defaults could lead to financial risk, massive layoffs could add to employment woes, and private firms could be further spooked,” Tang Renwu, who heads the School of Public Administration at Beijing Normal University, said.

- Reuters with additional editing by Mark McCord