(ATF) Global value chains are expected to diversify away from China in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic and the US-China trade war and India is hoping to position itself as an alternative manufacturing destination and unleash a wave of economic growth.

It is inevitable that global investors will undertake a comparison between the foreign direct investment (FDI) environment in the two countries. In the past five years, India has improved its ranking by 79 positions from 142nd to 63rd in the World Bank’s flagship Doing Business index.

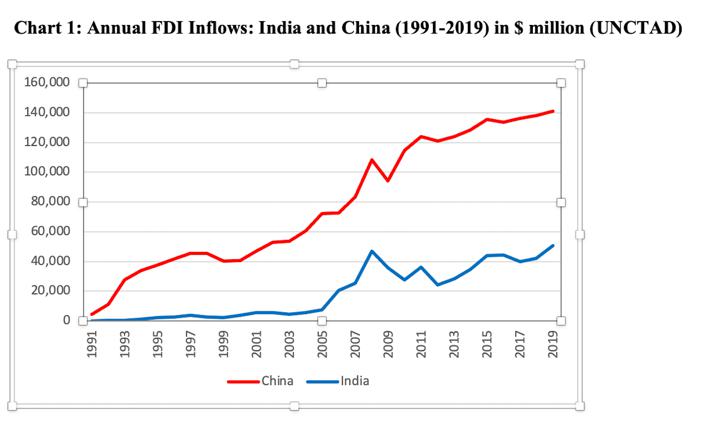

Is this sufficient to attract FDI? Statistics reveal a different story as India only managed to attract $49 billion of FDI in 2019 compared with $75 billion received by Brazil. Much like China, FDI in India is concentrated in a few regions, but there is a heavy tilt away from manufacturing.

China’s experience in attracting FDI is acknowledged to be effective notwithstanding concerns over neglect of labour and environmental standards. It has experimented with a wide range of strategies that have together managed to maintain consistent growth over three decades, achieve relatively better geographical and sectoral spread than India, and most importantly help make China a global manufacturing powerhouse.

It follows that India can borrow of the successful strategies adopted by China to improve its FDI game.

The first lesson that China offers is that import substitution industrialisation has little chance of success. This should serve as ample warning to forces within India that seek to place excessive reliance on the recently unveiled Atmanirbhar Bharat campaign encouraging Indian “self-reliance”.

Political sincerity is required to tap FDI as a source of capital and technology. A hedging approach that balances between protectionism and free trade is fraught with danger as it can cast doubts in the minds of investors.

China: different legal set-up, better SEZ incentives

China’s efforts to court foreign investors were greatly aided by an exclusive legal framework that exempted them from the vagaries of the mainstream legal system. The Indian legal system follows the principle of national treatment and forbids preferential treatment to foreign investors thus losing out on an invaluable tool to attract FDI that China leveraged for several decades.

Special economic zones (SEZs) were an important conduit for FDI in China. In these demarcated administrative zones, foreign investors could enjoy preferential financial, investment and trade privileges. Inexpensive land, tax holidays, rapid customs clearance, tax exemption on imported raw material and exported finished products, relaxed political interventions, among other such policies, became central to attracting FDI.

India introduced a formal framework for establishment of Special Economic Zones in 2006 and has accorded approvals for the establishment of 426 SEZs up to date. Out of these only 262 are operational and 142 of these cater to the information technology (IT) and IT services (ITES). This leaves plenty of scope for improvement to make SEZs export hubs for manufacturing clusters.

Technology for access

Domestic linkages of FDI is another area in which China has excelled. After 1978, the idea of employing market access as a bargaining chip in exchange for advanced technology from foreign sources gradually rose to the top of the China’s national economic policy.

The law stipulated not only that the technology and machinery contributed by the foreign investors should be advanced and appropriate to China’s needs but it also contained a warning to foreign investors that they will be required to compensate their Chinese joint venture partner if it was discovered that they had injected outdated technology or machinery into their joint ventures.

This paved the way for a recurring financial notion of trading market access for technology in two ways: firstly, foreign investors were willing to pay for the cost of entrance by transferring part of their advanced technology and secondly, the Chinese side could gain bargaining leverage over foreign investors by approving their entrance to the domestic market.

Since India largely equated FDI reform to liberalisation of sectoral limits there has never been an incentive for foreign investors to consciously partner with domestic companies. Unlike China, India has never had a statutory framework to govern relationships between foreign investors and their domestic partners.

Local governments in China played an important role in attracting FDI. Large multinationals were targeted because they could improve economic and technology indicators, at a speed incomparable with smaller companies. These firms were regarded as the “dragon’s head enterprises”. In India, the ability of state governments to incentivise FDI is limited due to the distribution of legislative powers under the constitution.

Too little differentiation

A survey of state-level industrial policies in the most prominent FDI destinations within India reveals that there is much too little to differentiate between the tax incentives offered by various states. The thresholds of fixed capital investment and direct employment generation for qualifying as ‘mega projects’ that receive customised incentives are also similar.

Certain regions in China such as Guangdong leveraged their proximity to Hong Kong and Taiwan and courted smaller foreign investors. They prioritised the long-term development of domestic enterprises rather than indicators for political achievement. India has a robust scheme to promote medium-sized, small and micro enterprises within domestic industry.

However, when it comes to FDI it is hard to discern any such concerted efforts. FDI projects which fail to qualify as ‘mega’ projects seldom receive any attention from state agencies.

In sharp contrast with Guangdong, domestic enterprises were sacrificed in certain areas to promote sector-focused clusters. The Sunan Model, which was centred around the electronics industry in southern Jiangsu province, is a good illustration of this approach where leading consumer appliance companies regarded as four little giants – Xiang Xuehai, Great Wall, Peacock and Chunhua – were rescued by forming joint ventures with foreign players rather than the conventional exchange of technology for market access.

A precondition for these joint ventures was that the domestic firms had to abandon their original brands and produce exclusively under foreign brands. Sector-focused efforts in India have had little success with the notable exception of the phased-manufacturing programme employed in the mobile phone industry that managed to draw investments from Samsung, Xiaomi, Vivo and Oppo by progressively increasing customs duty for components.

In the absence of any national policy that identifies or allocates priority sectors among states, each state is free to choose certain sectors as “thrust sectors”. This has resulted in a lot of overlapping priorities between states and is also a source of confusion among investors looking to identify an investment destination.

As a result of such overlap, even when a potential foreign investor decides to locate its manufacturing unit in India there is a long gestation period during which it has to engage with multiple state governments often in direct competition with each other to obtain the best possible package of incentives.

Nuanced policy needed

India has not been able to realise its potential as an FDI destination over the last three decades despite successive liberalisation of sectoral caps and projecting the attractiveness of its domestic market.

A more nuanced FDI policy is required to attract global value chains and investors looking for alternatives to China. More specifically, the following objectives might be worth emulating:

- A national FDI policy to reduce overlaps between industrial policies of states and provide clarity to foreign investors about national priorities;

- Developing more parameters to judge the benefits of FDI such as technology, gaps in supply chains, export potential, ability to reduce imports, companies moving away from China, etc.

- A government-led SEZ policy that establishes and promotes specific locations for manufacturing units in relevant sectors rather than the present voluntary registration system;

- SME-focused incentives to draw niche players in industries that do not require economies of scale; and

- A robust technology policy focused on FDI to incentivise absorption of technology and localise research and development.

In addition to the above, India also needs to undertake periodic surveys or consultations among existing foreign investors to obtain a better understanding of bottlenecks that prevent them from achieving profitability or realising their expansion goals. Pain points such as land acquisition, availability of human resources and complex tax laws can be alleviated through constant reform.

India also needs to undertake damage control to re-assert its position as a viable FDI destination.

The recent decision of the Indian government to stay away from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership has dampened interest among potential foreign investors which were looking at India as a manufacturing destination for global exports.

The fact that more than 50% of the $36 billion in FDI that India managed to attract from April to August 2020 was cornered by a single business group also raises concerns about the politics-business nexus in India that might work against foreign investors.

In 2020, India has launched several laudable policy initiatives such as the Aatmanirbhar with production-linked incentives and export preparedness index which can be described as Make in India 2.0. Indeed, these are positive steps in the right direction.

However, the overall impression that a potential foreign investor gets of India as an FDI destination is still predominantly one of confusion.

Imagine a simple question such as “Which is the best location in India to manufacture product X?” It is bewilderingly complex to answer.

Ironically, India needs to learn from China’s own experience to capitalise on the window of opportunity presented by the global anti-China backlash.