(ATF) Given the incidence of frauds that have been erupting in the Indian banking system with unfailing regularity since 2012, a spike in the reported cases of bank swindling in the past financial year is hardly surprising.

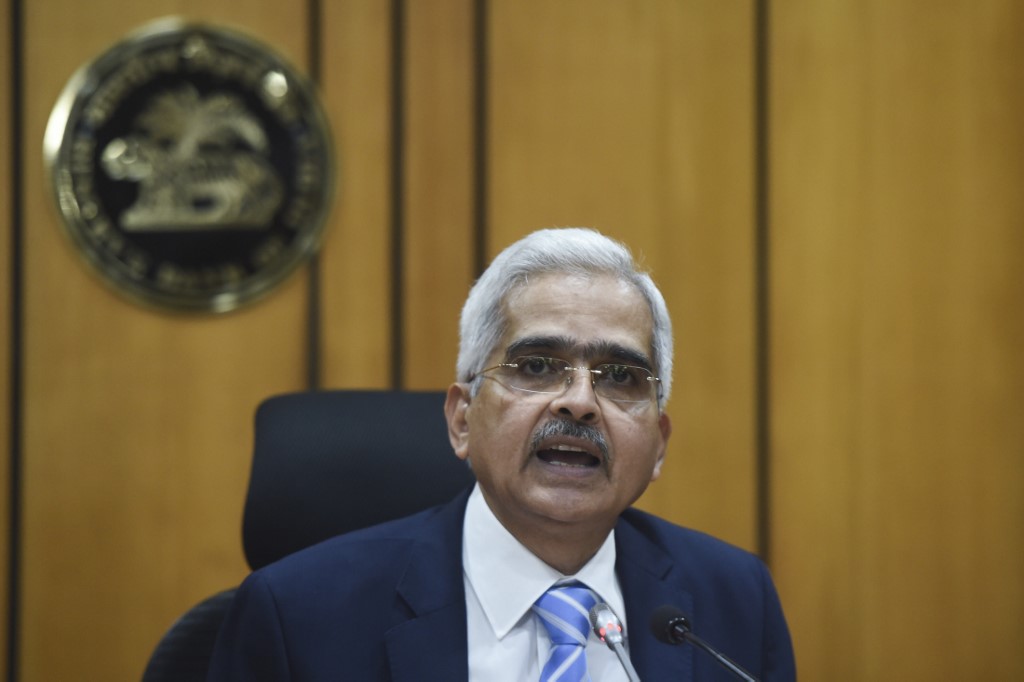

Still, when The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the central bank, in its annual report for the fiscal year ending March 2020 released some real numbers, the financial community was rudely shaken.

According to the report, the amount involved in banking frauds grew 2.5 times to $24.66 billion in the 2019-2020 fiscal year, compared with $9.5bn in 2018-2019.

The rise in the number of frauds was alarmingly high at 28% to 8,707 cases in 2019-2020 from 6,799 the year before.

“Public-sector banks were the worst hit as they accounted for $19.7bn or 80% of the amount involved in frauds during the year,” the report said. “Private-sector banks have been more vigilant in this regard as they accounted for 18.4% of the amount involved in frauds even though 35% of frauds were reported from private sector banks. The public sector banks reported for 50% of the fraud cases while foreign banks reported just 11%.”

According to the central bank, much of the swindling was due to loans made by Indian banks turning bad, both in terms of number and value. For instance, “the large value frauds, with the top credit-related frauds, constituted 76% of the total amount reported as frauds during 2019-2020, ” the report said.

Incidents relating to other areas of banking, such as off-balance sheet and foreign exchange transactions, however, fell in 2019-2020.

Lack of anti-fraud measures

“The problem with the banking system today is that it lacks the necessary anti-fraud mechanism or techniques to identify whether a borrower is genuine or a fraud,” said Vedant Sangit, a certified anti-money laundering expert at Indiaforensic, a fraud detection firm.

According to Vedant, banks often fail to conduct adequate due diligence to identify and gauge the extent of the risk involved in a lending operation. Consequently they are often unable to detect fraud early enough to prevent it.

The RBI too concedes that while the frauds framework focuses on prevention, early detection and prompt reporting, the average lag in detection remains long.

As an instance, RBI has cited that the average lag between the date of occurrence of frauds and their detection by banks was 24 months during 2019-2020. In large frauds – $13 million and more – however, the average lag was 63 months. The sanction of the credit facility in many of these accounts was much older.

Weak implementation of Early Warning Signals (EWS) by banks, non-detection of EWS during internal audits, non-cooperation of borrowers during forensic audits, inconclusive audit reports and a lack of decision making in “Joint Lenders” meetings account for the delay in detection of frauds, the report added.

“So, banks need to run extensive training programmes as well to equipment their employees with the capabilities of early fraud detection,” Vedant told ATF.

Economic downturn a culprit too

However, according to Jaikishan Parmar, an analyst with Mumbai-based Angel Broking, it is unfair to hold the weaknesses of the banking system wholly responsible for the surge of banking scams in the country.

“The irony is, if the Indian economy didn’t have to encounter the unfortunate crises of the past years like the global financial crisis, the demonetisation, the economic downturn subsequent to that demonetisation, and the shadow banking crisis of 2019 – all of which sucked the economy dry in terms of liquidity – many of the frauds could have been eventually covered up,” Jaikishan told ATF.

“If you analyse the pattern, what emerges is that most cases surfaced post 2016, the year from when India started announcing a series of fiscal measures and tightened compliance rules that prevented the loan defaulters to generate enough liquidity to prevent their loans turning bad,” he added.

That aside, the tightening of bank disclosure norms and ramping up of regulations by the RBI in the past 18 months have also led to higher disclosures of frauds by banks, he added.

Making amends

Nevertheless, the central bank has started ramping up its vigilance. While the EWS mechanism is getting revamped, RBI is strengthening the concurrent audit function, by mandating timely and conclusive forensic audits of all borrower accounts under scrutiny, the central bank’s annual report said.

An Advisory Board for Banking Frauds was also created in consultation with the Central Vigilance Commission, that will act as the first level of examination of all large-value fraud cases before recommendations are made to the investigating agencies.

Among other initiatives during 2019-2020 was the formation of a standing committee on analytics comprising experts from institutions such as the Indian Institute of Technology, Indian Institute of Management, and Indian Statistical Institute.

This will help the Indian banking industry to set up and adopt best practices in business intelligence and data analytics for risk modelling that would deliver improved inputs to bank managers, the RBI said.