This isn’t exactly the kind of news market embattled liquefied natural gas (LNG) producers wanted to hear, but for India it’s a hydrocarbon bonanza that will change its energy future.

On Friday, Mumbai-based Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL) and oil giant BP started producing the first gas at India’s initial ultra-deep water gas field, the R Cluster in block KG D6, some 60 km off the country’s east coast.

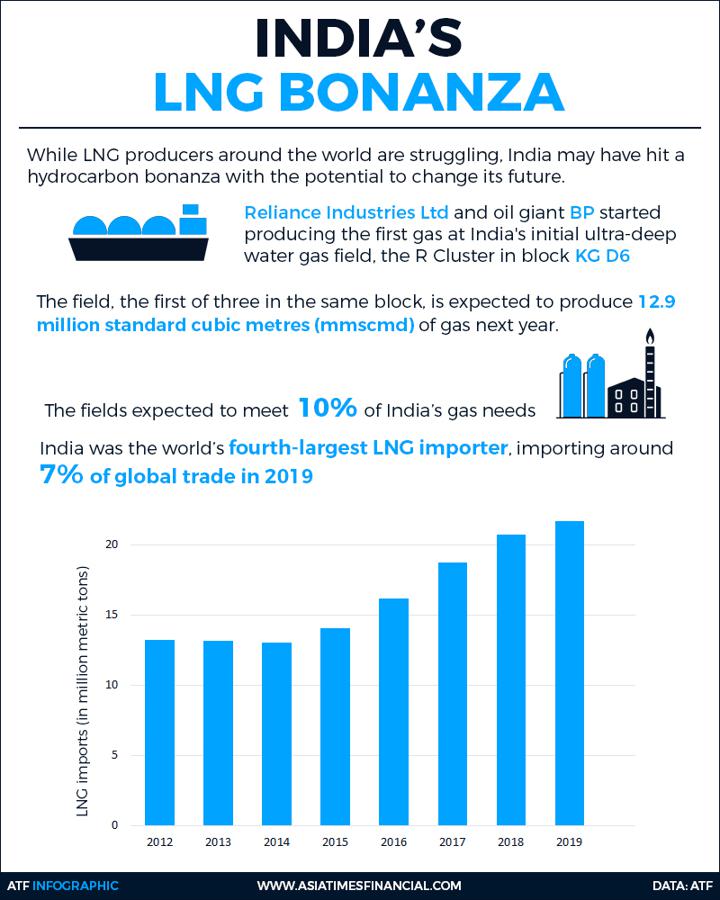

The field, the first of three in the same block, is expected to produce 12.9 million standard cubic meters (mmscmd) of gas next year.

The next project, the Satellites Cluster, is expected to come on-stream in 2021, followed by the MJ project in 2022. RIL holds a 66.7% stake in the project and BP a 33.3% stake.

The first field by itself will meet around 10% of India’s gas needs, while at peak production, all three fields are expected to produce around 30 mmscmd (1 bcf/d) by 2023, representing around 25% of India’s domestic gas production, and meeting 15% of the country’s insatiable gas demand by that time period.

India has already earmarked that cleaner burning natural gas make up 15% of its overall energy mix in just ten years, from 6.25% currently – no small feat for a country’s whose domestic gas production had bottomed out, forcing it to rely on more costly imported LNG.

After sharply declining from peak production in 2010, India’s dry natural gas production remained flat at about 1.1 trillion cubic feet (tcf) between 2015 and 2019, the US Energy Information Administration (IEA) said in its most recent analysis of India’s energy sector.

READ MORE: Iron ore ‘skysurge’ unsustainable, China industry chief warns

PRODUCTION FALL

Production in the first few months of 2020, however, fell substantially from the year before because of the Covid-19 pandemic and the national lockdown.

For a number of years, because of insufficient fuel supply for power generation and transmission capacity, India has suffered from electricity shortages, leading to rolling blackouts. As such, production from the Reliance-BP field is also a boon for the country’s efforts to offset politically and economically damaging black and brownouts in much of the country.

Moreover, since it’s cleaner burning gas it will help further New Delhi’s green energy pivot, which includes more LNG fuelling stations for the country’s trucking sector and its auto makers manufacturing more compressed natural gas (CNG) cars.

CNG-powered vehicles already make up around 9% of the company’s overall vehicle sales, while its largest car maker Maruti Suzuki India (MSI) already has eight CNG-powered cars in production, with other Indian car makers in hot pursuit.

India’s new offshore gas production also comes at a pivotal time for both India as well as LNG markets in the Asia-Pacific region, home to around two-thirds of global LNG demand.

4TH LARGEST IMPORTER

India was the world’s fourth-largest LNG importer, importing about 1.2 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of the fuel, around 7% of global trade in 2019, according to the EIA. During the past two years, India’s LNG procurement has spiked some 25%.

Earlier this year, India commissioned its sixth LNG import terminal, with four more under construction. This build-out has seen India capitalise on LNG spot prices that hit record lows by April, from both Covid-19 demand destruction and over-supply, plunging beneath the US$2 per million British thermal units (MMBtu) price point – below most producers’ break-even points.

However, in the last month prices have resuscitated amid the onset of colder temperatures in North Asia, outages at major production hubs and congestion along global shipping routes.

Prices for the super-cooled fuel last week hit a six-year high of more than US$12 per MMBtu. However, LNG prices are seasonal and historically pull back with the onset of spring and warmer weather.

SUPPLY OVERHANG

However, what’s good news for India is not necessarily good news for LNG producers, ranging from Qatar to the US, to Australia and back again. LNG markets, both globally and especially in the Asia-Pacific region, have been locked in a severe supply overhang, with corresponding lower prices for several years.

The supply glut for its part has coincided with (and even given new impetus to) changing contractual dynamics for how the fuel is bought and sold, ranging from reducing the duration of off-take agreements, historically around 15-20 years, to the removal of restrictive destination and other clauses, as well as reducing the amount of deals based on an oil indexation formula.

India with its insatiable energy demand and LNG build-out was one of the few bright spots in an otherwise dismal market for LNG producers. The country has been making more LNG procurement deals. However, with an extra 30 mmscmd worth of domestic gas production by 2023, and less but still stable supply further out from the three fields, the country will be less reliant on LNG imports, exacerbating the overhang situation and possible pushing out any semblance of market equilibrium in Asia by a number of years.

FUTURE PULL-BACK

Offsetting India’s future pull-back on LNG imports will be demand from China (which will eclipse Japan for the top LNG importer slot within the next two or three years), Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam which, for its part, now has as many as 22 new LNG-to-power project proposals in its new Power Development Plan (PPD) VIII, to be released by the Prime Minister’s office at the start of the year.

“They are selling gas via auction to long-term buyers, so those relying on LNG will cut back their requirements as they will get assured supplies from us, however, demand for gas is huge so it depends on importers and terminals how they adjust supplies,” said an industry expert.

Nonetheless, as India becomes more able to meet its own gas needs, it will be able to dictate even more contractual terms over the LNG it will still need, as well as helping other buyers of the fuel follow the same path.