(ATF) India’s central bank monetary policy committee decided today to hold its key rates given the uncertain outlook on inflation, plus supply chain disruptions, upside risks to food prices, continued subdued demand for loans, and the likelihood of a post-Covid crisis for large and small companies.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced the decision despite its own prediction that the economy would contract in the first half and over the full year. Leading economists have forecast that the Indian economy will contract by about 5% to as much as the low double digits.

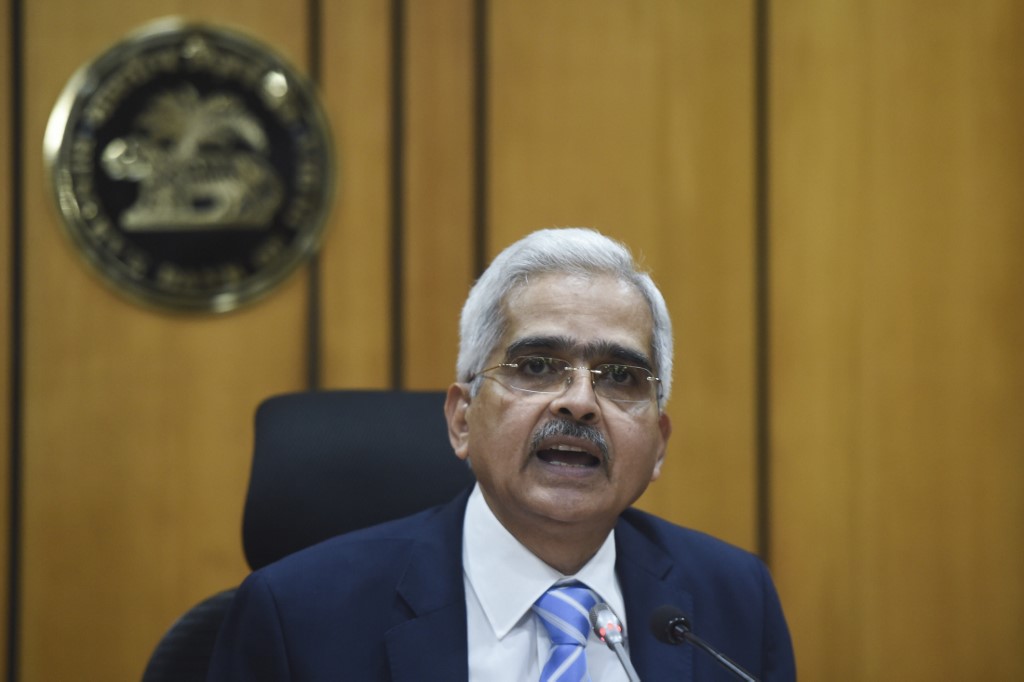

“The real gross domestic product growth in the first half of the year is estimated to remain in the contraction zone,” RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das said. “A more protracted spread of the pandemic, deviations from the forecast of a normal monsoon and global financial market volatility are the key downside risks.”

Borrowing by industry and services, or the so-called non-food bank credit, grew at a modest 5.6% as of mid-July, it said. This was despite borrowing costs plunging to the lowest in a decade because of plentiful availability of cash in the banking system. The outlook remains hazy also because of low consumer confidence in July compared to earlier months.

Still, the transmission of RBI policy rate cuts has been muted. Banks have been able to lower their weighted average lending rate by only 47 basis points from the 115 basis points cut in the repo rate by the RBI in March, when India imposed the world’s biggest and one of the most severe lockdowns to contain the spread of coronavirus.

Borrowing against gold

Recognising the fall in income because of the two-month nationwide lockdown and sporadic lockdowns at state levels, the RBI relaxed rules for borrowing against gold. India has one of the largest reserves of gold in personal holdings. Lenders can give loans of up to 90% of the value of the gold now compared with 75% of its value earlier.

The central bank did not specify a figure for how much GDP growth might decline or how much the inflation rate may rise by the end of the year. Yields on government bonds maturing in 10 years were little changed around 5.85%.

“The outlook for growth continues to be negative with the RBI refraining to give any number to the extent of GDP contraction on account of Covid-19,” Rajnish Kumar, chairman of the State Bank of India, said. “The asymmetric recovery across rural and urban areas poses a challenge in policy formulation. The outlook on inflation is equally uncertain as supply shock has limited the scope of monetary policy in containing risk.”

Inflation as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) accelerated to 6.1% as of June, compared with 5.8% in March, and inflation pressure is evident all sub-categories. The government’s decision to raise retail prices of petrol, diesel and cooking gas despite a fall in global crude oil prices is also expected to add to a higher inflation rate.

‘Prudent decision’

SBI’s Kumar said the decision to hold the policy rate was a prudent one given the prevailing circumstances as the trajectory of economic growth, inflation and external demand continues to remain uncertain.

Anagha Deodhar, an economist with ICICI Securities, said holding rates steady also showed that the ability of just the monetary policy to stimulate growth was limited.

To help overcome the uncertain economic conditions, the central bank said it will help large and medium-sized companies to restructure their loans so that their borrowings don’t get classified as bad loans.

Non-performing loans have been a bane for not just the borrowers but also lenders. Being branded as a defaulter or a near-defaulter makes it tougher and expensive for a borrower the next time around. It also restricts the bank from giving out more loans, since it has to set aside a larger sum of money from its reserves to cover bad loans.

Bad loans tipped to rise

The RBI, in its July 24 Financial Stability Report, predicted that banks’ ratio of non-performing assets could rise to as high as 14.7% of all loans by March 2021 in the case of a very severe stress scenario – up from 8.5% as of March 2020. For state-run banks, it said bad loans could hit 11.3% as of March. But private sector banks might only face NPAs at 4.2% of total loans at that time, it predicted.

With the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) sliding for a fourth month along with India’s exports and imports, bankers and economists are looking toward the government for fiscal measures.

“We think the economy will suffer its largest contraction on record this year,” Shilan Shah, the senior India economist at Capital Economics wrote in a note.

“While the nature of the crisis means that fiscal policy should be doing more of the heavy lifting, there is still a role for the RBI. But with the economic outlook this poor, we still expect a resumption in the monetary easing cycle.”