(ATF) Feelings against China are running so high across the US political spectrum that Beijing should expect a continued rough ride under Joe Biden. For if he becomes president the Democratic nominee is likely to revive alliances that Donald Trump has scorned to press China on everything from unfair competition to human rights.

Only cooperation on global warming holds out slender hope of better ties.

One school of thought has it that China’s Communist leaders want to see the back of Trump, especially since he has repeatedly blamed China for the global Covid-19 pandemic.

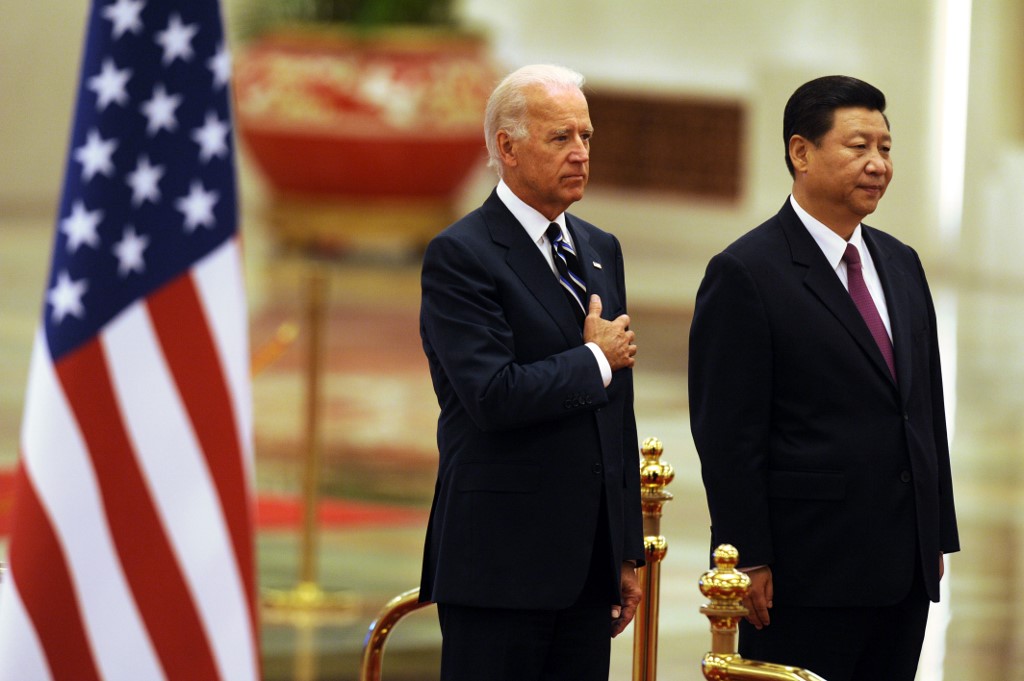

If so, they should be careful what they wish for. It is Biden, not Trump, who has called Xi Jinping a “thug”. And although Biden says Trump’s tariffs on Chinese imports have hurt American businesses and consumers, he has also called for the US to “get tough on China”.

“The extent of suspicion, if not outright fear and anger, at China is widely held in Washington,” said Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “So very aggressive measures against China will continue to be taken.”

For instance, a Biden administration was likely to keep using unilateral financial sanctions, such as those imposed on Iran and Venezuela, to help achieve its foreign policy and economic goals.

But Posen said Biden was committed – as a matter of effectiveness as much as principle – to forge a common front with key allies on China trade issues.

A working group of senior officials from the US, the European Union and Japan was already drawing up proposals to tackle unfair Chinese industrial subsidies at the World Trade Organisation – if need be via “plurilateral” talks among like-minded countries rather than the full WTO membership, Posen said.

Such an approach would mark a big departure from Trump, who openly disdains international organisations or alliances that he sees as tying America’s hands.

Europe getting tougher on China

Cecilia Malmström, a former EU trade commissioner, listed a number of areas where she said US criticism of China was broadly shared in Europe, including the absence of a level playing field for foreign businesses in China, cyber theft and the dumping of goods at unfairly low prices.

“Europe is getting tougher on China,” she said. “Europe doesn’t share the US tactics, but we share a lot of the strategy, so I think we can build something together.”

Malmström suggested creating a transatlantic working group to identify core issues of mutual concern. As well as trade matters, she said there could be a case for a joint boycott of goods shown to have been made by forced labour in the far western region of Xinjiang. (China rejects Western charges of forced labour. It says Uighurs and other Muslims in Xinjiang are receiving vocational training to improve their job opportunities.)

“If we can do that together, all 27 of us (EU members), with the US and others, I think we have a bigger chance of succeeding,” Malmström said.

There is no guarantee, however, that the EU will be able to find common cause. In particular, America’s determination to thwart China’s high-tech ambitions – exemplified by its campaign against Huawei – is testing European unity.

The EU may agree with the US that Chinese technology poses a national security threat, but China is a major trade and investment partner. Europe cannot afford not to keep engaged.

Guntram Wolff, the director of Bruegel, a Brussels think-tank, said he was worried that Washington’s hard line against China on technology could become a serious headache for Europe by disrupting its supply chains or even subjecting its firms to secondary sanctions.

“We are in for a real risk that this could be extremely messy and difficult for European companies, no matter who is in the White House,” said Wolff, who led a webinar with Posen and Malmström.

So far, so dispiriting for investors counting on a Biden presidency to steer America’s international relations into calmer waters.

But there is one area where the interests of the US, Europe and China are more closely aligned – climate change.

Xi Jinping sprang a surprise at the UN General Assembly in September when he committed China to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2060, just 10 years later than the EU; Brussels is putting green growth at the heart of its post-Covid economic recovery plan; and Biden, who had already pledged to rejoin the Paris accord to cut greenhouse gas emissions, called in his second televised debate with Trump for a transition away from oil and gas.

If Xi and Biden want to take Sino-American ties out of the deep freezer, cooperation in the run-up to next year’s climate change summit in Glasgow offers a timely opportunity.

‘China must demonstrate credibility on its climate goals’

Scepticism about China’s 2060 goal is warranted given the magnitude of reforms it will require. But the very act of proclaiming a target in public reflects real high-level commitment to decarbonisation, according to Ilaria Mazzocco, a researcher with the Paulson Institute in Chicago.

“To have any hope of reaching the 2060 goal, however, China will have to first demonstrate its credibility in the medium term,” she argued.

One way would be to raise the 2025 target for the share of non-fossil fuels in China’s primary energy consumption, currently 17.5%. The five-year plan for 2021-2025, being finalised at a Communist Party plenum this week, will be scrutinised for clues to Beijing’s intentions.

After four years of rocky ties, it’s a stretch to imagine the US and China swapping decarbonisation schedules instead of insults. Equally, however, going into the 2016 election few would have predicted such a swift deterioration in bilateral relations.

Biden’s priority will be to bind domestic wounds and revive the post-pandemic economy, while Xi has shown no sign of dialling down his strident nationalism.

But, should they choose, the November 2021 conference in Scotland offers them a chance to demonstrate the leadership that the world has sorely missed.