The encrypted messaging app Telegram is used extensively by powerful criminal networks in Southeast Asia involved in online scam operations plundering billions from victims worldwide.

The crime gangs mostly use crypto – notably USDT, a ‘stablecoin’ launched by Tether – when doing international deals and laundering the proceeds of large-scale illegal activity. Deepfake video, audio and pictorial services are another troubling new ‘weapon’ being utilised by some of these modern-day crime hubs.

These are three technical developments that authorities around the world are struggling to counter, according to a new report by the UN Office for Drugs and Crime released on Monday.

ALSO SEE: Mass Arrests in India as Samsung Workers’ Protest Drags on

The UNODC report says extensive use of Telegram has enabled a fundamental change in the how crime gangs now operate.

It has some of the latest allegations to be levied against the controversial encrypted app since France, using a tough new law with no international equivalent, charged its boss Pavel Durov for allowing criminal activity on the platform.

Hacked data including credit card details, passwords and browser history are openly traded on a vast scale on the app which has sprawling channels with little moderation, the UNODC report said.

Tools used for cybercrime, including so-called deepfake software designed for fraud, and data-stealing malware are also widely sold, while unlicensed cryptocurrency exchanges offer money laundering services, according to the report.

“We move 3 million USDT stolen from overseas per day,” the report quoted one ad as saying in Chinese.

There is “strong evidence of underground data markets moving to Telegram and vendors actively looking to target transnational organized crime groups based in Southeast Asia,” the report said.

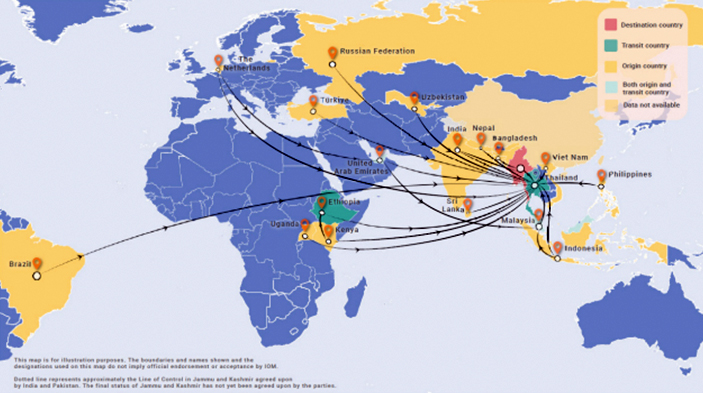

Southeast Asia has emerged as a major hub for a multi-billion-dollar industry that targets victims across the world with fraudulent schemes. Many are Chinese syndicates that operate from fortified compounds staffed by trafficked workers.

The industry generates between $27.4 billion to $36.5 billion annually, according to UNODC. However, a study group led by the US Institute for Peace estimated total proceeds from scamming last year was far higher – $64 billion.

Russian-born Durov was arrested in Paris in August and charged with allowing criminal activity on the platform including the spread of sexual images of children. The move has put the spotlight on the criminal liability of app providers and also triggered debate on where freedom of speech ends and enforcement of the law begins.

Telegram, which has close to 1 billion users, did not immediately respond to a request for comment, Reuters said on Monday.

Following his arrest, Durov, who is currently out on bail, said the app would hand over users’ IP addresses and phone numbers to authorities making legal requests. He also said the app would remove some features that have been abused for illegal activity.

Benedikt Hofmann, UNODC’s deputy representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, said the app was an easily navigable environment for criminals.

“For consumers, this means their data is at a higher risk of being fed into scams or other criminal activity than ever before,” he told Reuters.

Malware, AI, deepfakes

The report said the sheer scale of the profits earned by criminal groups in the region had required them to innovate, adding they had integrated new business models and technologies including malware, generative artificial intelligence and deepfakes into their operations.

UNODC said it had identified more than 10 deepfake software service providers “specifically targeting criminal groups involved in cyberenabled fraud in Southeast Asia”.

Elsewhere in Asia, police in South Korea – estimated to be the country most targeted by deepfake pornography – have reportedly launched an investigation into Telegram that will look at whether it abets online sex crimes.

Reuters reported last month that a hacker used chatbots on Telegram to leak the data from top Indian insurer Star Health, prompting the insurer to sue the platform.

Using the chatbots, Reuters was able to download policy and claims documents featuring names, phone numbers, addresses, tax details, copies of ID cards, test results and medical diagnoses.

Responses differ in each country

The UN report said ASEAN nations responded differently to crimes at the scam centres. Lao officials, it said, “initially refused to intervene as the crimes had been committed within the SEZ. It was only after increased pressure from the Royal Thai Government that Lao PDR officials contacted the ‘managers’ of the SEZ asking them to release any Thai nationals held against their will.

Cambodian police, meanwhile “will often approach the scam compound, hand over a list of people’s names to the compound guard (a list of the victims who have contacted their embassy or other entities asking for help in being released), and ask for the release of these specific individuals,” it said.

But in Myanmar, there were “significant barriers to conducting initial identification and release of potential victims due to the challenging conflict situation and the [legal set-up of] special regions,” it said.

By 2023, the identification and release of trafficking victims in Myanmar “had become extremely challenging, especially for victims confined in areas not under any form of control by the Myanmar government, and even more so for victims held in remote areas of the country.”

here was also no standard operating procedure on how to conduct rescue operations, the report said.

“Without written standards and guidance for the initial identification of potential victims, relevant state authorities have struggled to respond as government actors and their responsibilities with regard to initial identification and release remained unclear.”

Another factor complicating possible rescue operations was the fact that some of the people in scam compounds may not be trafficking victims.

“During 2020-2022, nearly all of the people committing the online scams and fraud in the scam compounds were trafficking victims,” it said.

“However, in 2023, this dynamic appears to have changed, with people becoming more aware of the conditions in the scam compounds, but going there nonetheless because of the attractive salary and potential commissions if they perform well. Many may still become victims of exploitation once the threats materialize and they are not able to leave.”

And now, scamming operations have spread to Malaysia – in Langkawi, Johor and other sites, although it said they were much smaller than in Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia.

“Thailand has also been identified as an emerging destination country for such organized crime activities,” it said.

Meanwhile, authorities in the Philippines arrested over 350 foreigners, mostly Chinese in a raid last week on a centre in Manila where online fraud and illegal gambling reportedly continued despite President Ferdinand Marcos Jr banning such activity in July.

In late August, more than 160 foreign nationals were also arrested during a raid on a resort in Lapu-Lapu city in Cebu municipality in the Philippines.

- Jim Pollard with Reuters

ALSO SEE:

Weak ASEAN Nations ‘at Risk of Evolving Into Scamming States’

‘US to Sanction Prominent Cambodians Tied to Scam Centres’

N Korean Hackers Used Cambodian Firm to Launder Stolen Crypto

Scamming Compounds in SE Asia Stole $64 Billion in 2023: Report

High-Tech Asian Crime Wave: Cyber Scams, Casinos Loot Billions

Big Tech ‘Doing Little’ to Counter Rampant Scams on Social Media

Macau Junket King Alvin Chau Gets 18 Years For Casino Crimes

Crime Gangs Control Some Myanmar, Laos Economic Zones: UN