Britain will on Wednesday unveil legislation that it admits breaks international law by rewriting parts of its Brexit divorce treaty relating to Northern Ireland, sparking widespread criticism and clouding the latest round of fraught EU trade talks.

After leaving the European Union early this year following a bitterly divisive referendum, Britain is racing to agree a trade deal with Brussels as the clock ticks down to a crunch EU summit in mid-October.

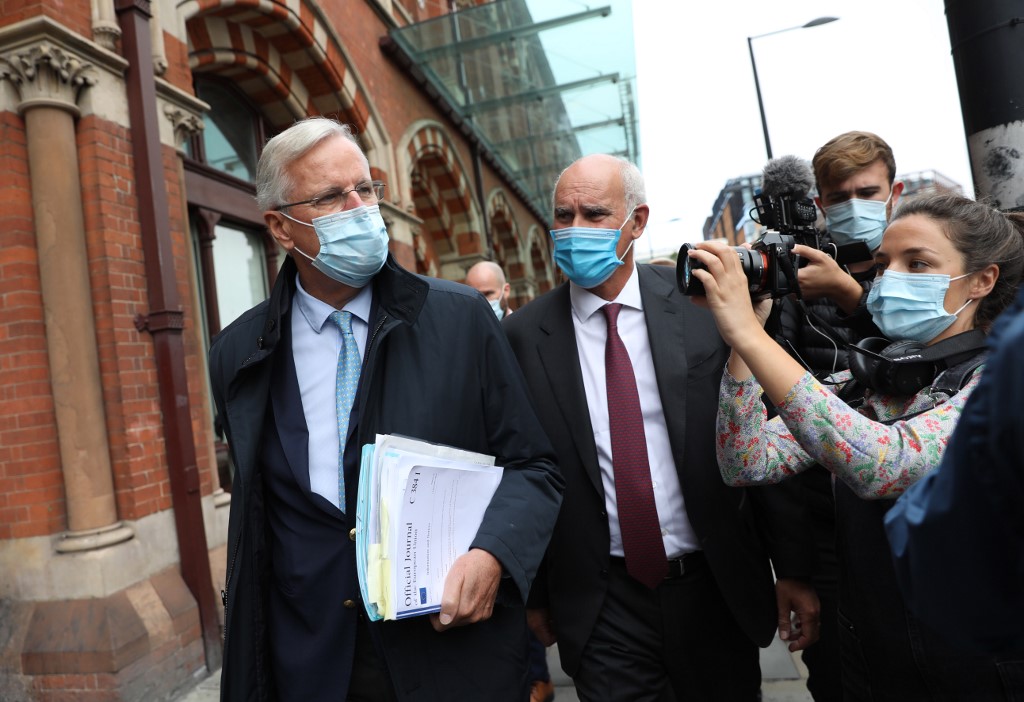

An eighth round of talks began in London on Tuesday.

Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney, whose country is the EU nation most affected by Brexit, warned that reneging on last year’s divorce pact “could seriously erode and damage political trust”.

European Parliament president David Sassoli added: “Any attempts by the UK to undermine the agreement would have serious consequences.”

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said Britain will cope with the economic dislocation of leaving the transition period at the year-end without a deal, despite also facing the coronavirus crisis.

But the prospect has caused the pound to slump on currency markets and made UK businesses increasingly anxious.

Johnson’s government has urged Brussels to show “more realism” about dealing with a heavyweight economic power on its borders.

It insists the changes to the Withdrawal Agreement it will publish on Wednesday are technical and required to ensure businesses in Northern Ireland can enjoy friction-free trade with both the EU and the rest of the UK from next year.

Responding to a question in parliament, Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis conceded: “Yes, this does break international law in a very specific and limited way.”

Lewis said there were “clear precedents” for such a move as circumstances change.

But in Dublin, Coveney said the comments were “gravely concerning” and said he had asked the Irish ambassador to raise the issue directly with London.

Shock in US

Britain also faced warnings from across the Atlantic of consequences for a separate US-UK trade deal if it backtracked on the Brexit deal.

House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi warned last year that a deal between London and Washington would be dead on arrival in Congress if the peace accord that ended decades of bloodshed in Northern Ireland were undermined.

On Tuesday, Democrat Congressman Brendan Boyle told BBC radio it “would be very difficult to enter into a trade negotiation with a party that would have just ripped up a very important agreement to us”.

There was criticism at home in Britain, too, with former prime minister Theresa May and the main opposition Labour party both expressing alarm.

Jonathan Jones, the head of the government’s legal department, was also revealed to have resigned, in a move the Financial Times linked to the Northern Ireland row.

It reported he was “very unhappy” about the decision to rewrite the Northern Ireland Protocol – a vital part of the EU withdrawal pact designed to avoid a return to the unrest that stalked British rule in the province.

Johnson’s spokesman said the government was “fully committed to implementing” the protocol.

But he stressed “we cannot allow damaging default provisions to kick in” for Northern Ireland if London and Brussels fail to negotiate a deal this year.

The British government’s claim that it has only now found problems with the protocol prompted disbelief from opposition parties.

They seized on Jones’ exit to level new charges of incompetence against Johnson after months of policy U-turns in his government’s coronavirus response.

Britain and the EU agree a deal must be struck by next month’s EU summit, to give time for translation and parliamentary ratification before the end of 2020.

But divisions remain on totemic issues such as state subsidies for industry and fishing rights.

Northern Ireland will have Britain’s only land border with the EU, and the Brexit protocol means the territory will continue to follow some of the bloc’s rules to ensure the frontier remains open.

Removing a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom, was a key part of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that brought an end to 30 years of violence.

By Jitendra Joshi with Joe STENSON in Dublin for AFP