Much has been written about a possible Chinese takeover of Taiwan, the threat such an invasion would pose to other regional countries and what the United States might or might not do in response.

Books and articles have expounded on the political, military and geostrategic aspects of the problem, with intriguing maps of the first and second island chains blocking China’s access to the Pacific Ocean.

But these analyses about Taiwan’s fate often ignore one of the most worrying aspects of the problem: American reliance on Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturing.

As David Arase, professor of international politics at the Hopkins-Nanjing Center of the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, notes, “Even an unsuccessful invasion of Taiwan would cause a supply chain disruption.”

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has, of course, received a lot of press coverage in regard to America’s dispute with Chinese tech giant Huawei.

Under pressure from the US government, TSMC stopped taking orders in mid-May from Hi-Silicon, the integrated circuit design arm of Huawei. In 2019, Hi-Silicon had accounted for 14% of TSMC’s revenues. So the halt represented a substantial sacrifice for TSMC.

TSMC has also agreed to build a factory in Arizona to help bring the semiconductor industry back to America, even though it’s not an economically sound proposition.

However, considering that TSMC’s founder, the legendary Morris Chang, spent 25 years at Texas Instruments, this is not as surprising as it might seem. Most of TSMC’s business comes from America.

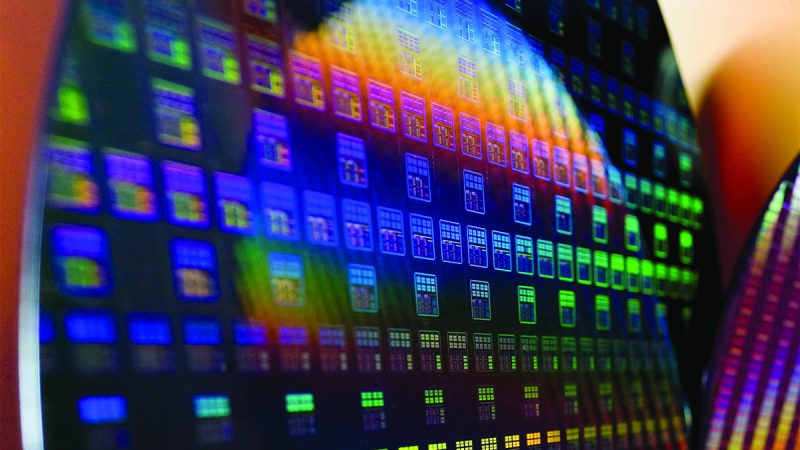

TSMC is the world’s largest and most technologically advanced dedicated semiconductor foundry, with about half of the global market for contract chip manufacture.

TSMC produces semiconductor devices designed by AMD, Apple, Broadcom, Nvidia, Qualcomm, Xilinx, Texas Instruments and other American companies; by Japanese semiconductor makers Renesas and Sony; and by European companies NXP and ARM (owned by Japan’s Softbank).

All these companies are top tier and TSMC itself ranks third in global semiconductor revenues. In 2019, the seven American companies accounted for close to 55% of TSMC’s revenue. With the exception of Texas Instruments, they are “fabless” design companies, meaning that they do not have their own commercial production (fabrication) facilities.

New US Department of Commerce chip ban may not have the desired punitive effect. Image: Twitter

We can imagine what might happen if Taiwan were absorbed by the People’s Republic of China, if Communist Party “observers” were added to TSMC’s top management and if a Party committee were implanted within its organization. TSMC’s customers’ design secrets could be compromised and, depending on the political situation, their production schedules might not be met.

Dissatisfied customers could go elsewhere, but that would not be easy and would take time, other semiconductor foundries being much smaller and having a narrower range of capabilities. Samsung’s foundry business, the industry’s second-largest, is less than 40% the size of TSMC’s; third-ranking GlobalFoundries’, an American company, is less than 20%. Fourth-ranking UMC is also Taiwanese and fifth-ranking SMIC is Chinese.

The Americans could (and no doubt will) expand their own semiconductor production capacity, but that is an expensive, long-term proposition. The US currently accounts for only about 13% of global capacity and less than 10% of investment in new capacity. In contrast, the Semiconductor Industry Association calculates that American companies accounted for 47% of global semiconductor sales in 2019.

The recent experience of Micron Technology is enlightening. Micron, headquartered in Boise, Idaho, is a multinational company with production facilities in the US, Singapore, Japan, Taiwan and China. It ranks third in the dynamic random-access memory chip market after Samsung and SK Hynix of Korea.

In 2017, Micron sued Taiwanese foundry UMC and its Chinese client Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit for infringement of its DRAM patents, alleging unauthorized transfer of its intellectual property to Fujian Jinhua.

The 2016 founding of government-owned Fujian Jinhua was part of China’s campaign to develop its own memory chips and reduce dependence on imports.

In 2018, the US Department of Commerce banned exports of equipment and technology to Fujian Jinhua and the Department of Justice indicted both UMC and Fujian Jinhua for industrial espionage. That crippled Fujian Jinhua’s DRAM project, which was shut down in 2019.

A Chinese semiconductor worker in a file photo. Photo: Facebook

In June this year, a Taiwanese court ruled that two engineers who had worked for Micron before joining UMC were the source of the stolen intellectual property.

Meanwhile, in 2018, UMC countersued in China, where a court ruled that Micron had infringed on UMC’s patents. And earlier this year, China’s first DRAM chips – made by ChangXin Memory Technologies, which was founded the same year as Fujian Jinhua – appeared in storage devices sold in China.

Imagine an exponential increase in this sort of thing, but with the Taiwanese courts on China’s side.

Scott Foster is an analyst with LightStream Research, Tokyo.