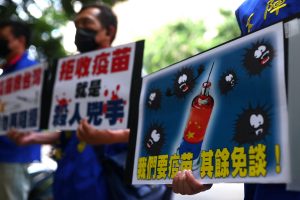

(ATF) A fast-spreading political mutation of Covid seems to be threatening to prolong the damage to the global economy caused by the virus. It is called vaccine nationalism.

A row this week between the European Commission and the Anglo-Swedish pharmaceuticals company AstraZeneca over delays to the delivery of coronavirus jabs offers a taste of the wrangling in store over how to ensure the equitable distribution of life-saving vaccines to poor countries as well as the rich.

Wealthy countries are disagreeing over “who gets how much, while the rest of the world looks on”, Winnie Byanyima, executive director of UNAIDS, told a Chatham House event this week.

The stakes – moral, political, economic – are enormous. For this is a global pandemic. So if Covid is not contained in developing nations, advanced economies are likely to have to continue to live indefinitely, to some degree at least, with suffocating travel and quarantine restrictions.

As part of the Covax programme to share Covid vaccines around the world, $2.4 billion was raised last year to give low-income and middle-income countries access to 1.3 billion doses.

But Covax, a World Health Organisation and Gavi Vaccine Alliance initiative, has yet to start deliveries. As of last week, Guinea was the only one of 29 low-income countries to have begun vaccinations, according to WHO officials. A total of 55 people out of a population of more than 12 million had been inoculated.

And in any case, the 600 million doses that Covax has earmarked for Africa will be enough only for 20% of the continent’s population, according to South African President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum’s virtual Davos Agenda meeting this week, Ramaphosa blasted rich countries for hoarding vaccines by buying up to four times more than they required: “This is being done to the exclusion of other countries in the world that most need this.”

Furious European Commission

The European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, is furious that AstraZeneca says it will be able to deliver only a quarter of the 100 million vaccine doses expected by the end of March but will keep supplying 2 million doses a day to the UK government. Several EU member-states have had to suspend or slow their vaccination programmes because of a shortage of doses.

Astra Zeneca blames production problems at a plant in Belgium and says that it merely pledged “best efforts” to supply the vaccine, which it developed with Oxford University. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen retorts that the contract is “crystal clear”.

The rights and wrongs of the row, which may go to arbitration, are less interesting than Europe’s reaction: the commission, usually a stout advocate of free trade, announced plans to give national regulators the power to reject requests to export the vaccine. That could lead to a ban on millions of doses destined for Britain, which since January 1 is no longer a member of the bloc.

Given the intricacy of global supply chains, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations warned that export curbs would undermine the supply of vaccines in Europe and around the world.

“Risking retaliatory measures from other regions at this crucial moment in the fight against COVID-19 is not in anyone’s best interest,” the trade group said.

Vaccine diplomacy

Vaccine jousting is not confined to Europe. India is giving millions of doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine to South Asian countries, to forge friendships and push back against China’s influence in the region. The vaccine is manufactured by the Serum Institute of India, the world’s biggest producer of vaccines.

If vaccine nationalism were to spread and developing countries had insufficient access to coronavirus tests and treatments, the global economy could lose as much as $9.2 trillion, according to a study commissioned by the International Chamber of Commerce. It reckons half of the cost would fall on advanced economies.

The International Monetary Fund has also sounded the alarm. Delayed, inequitable distribution of vaccines bodes ill for the global economy because emerging markets (EMs) accounted for about 65% of world growth in the period 2017-19, the IMF said in an update to its Global Financial Stability Report.

“Supply chain disruptions could affect corporate profitability even in regions where the pandemic is under control. And because growth is a crucial ingredient for financial stability, an uneven and partial recovery risks jeopardising the health of the financial system, the Fund added.

So, what is to be done? Joe Biden is rightly focusing on domestic priorities. But the new US president has an opportunity to reassert US leadership by coordinating a global response to the pandemic. Countries need to renounce vaccine protectionism and nationalism, waive intellectual property rights to speed vaccine manufacture and vastly increase the resources of Covax.

This is also an opportunity for the G20, so far missing in action on Covid, to show it remains relevant. It’s unfortunate that the group’s current chairman, Italy, is preoccupied with yet another domestic political crisis.

Rich countries understandably want to put their own populations at the front of the vaccine queue. They can afford to do so. Appeals to morality go only so far in a pandemic. But advanced economies have a clear self-interest not to neglect the urgent needs of emerging economies. For no one is safe from the virus until everyone is safe.

READ MORE: