Stocks that had lost most of their value in the past month led the Dow Jones Industrial average to a 10% gain, the best percentage gain since 1933 – which was not a particularly auspicious time to buy stocks.

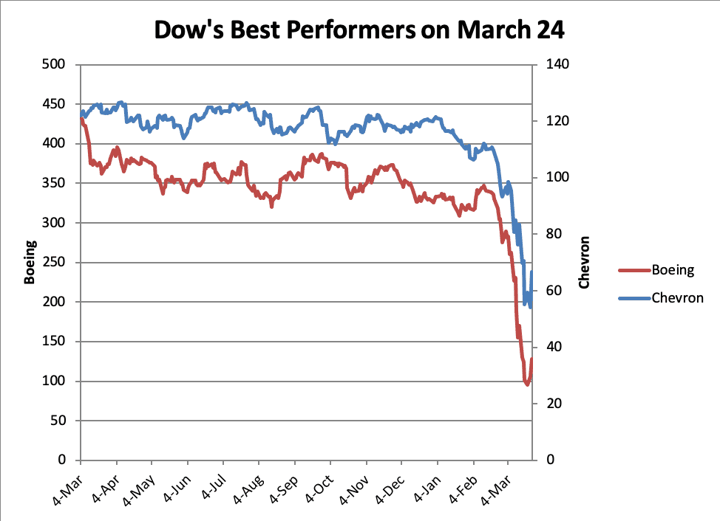

The Dow’s top performers gained more than 20%, but numbers are deceptive because the base from which the percentage gain was calculated had evaporated during the past month. This is clear from the chart.

After Boeing lost more than three-quarters of its market price, a 20% gain looks like a dead cat bounce. The Tuesday rally came on top of Monday’s crash, as investors attempted to sort out the implications of a $2 trillion spending program, White House suggestions that perhaps businesses could re-open sooner than expected and, most importantly, an unprecedented limitless quantitative easing program by the Federal Reserve. The Fed will buy not only Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by the government, but investment-grade corporate bonds, municipal bonds, commercial mortgage-backed securities and other risky instruments that the central bank has never touched.

Not everything rallied, however, and the dogs that didn’t bark in the night provide the most information, as in the Sherlock Holmes story “Silver Blaze.”

Although municipal bonds rallied in general on the prospect of Federal Reserve purchases, State of Illinois bonds barely moved. Barack Obama’s home state was paying 2% for seven-year money as recently as March 10, but the yield on its 5% bond of 11/0/2027 since jumped to 6%. With $60 billion of outstanding debt, Illinois will pay an additional $2.4 billion a year at that interest rate. Illinois also has a pension shortfall of about $241 billion, and spends a quarter of every taxpayer dollar on pensions. A death-spiral threatens in which higher interest rates and lower tax collections will bankrupt the state.

Before the crisis, state and local pension funds were about $5.4 trillion in the hole. The wipeout of their equity gains of the past three years as well as losses to their higher-risk fixed income assets will lead to a crisis.

The commercial paper market (short-term obligations of top-rated companies) remains paralyzed, with 90-day AA-rated paper paying 2.12% more than Treasury bills , from about even a month ago. That means that top corporations are unable to fund short-term.

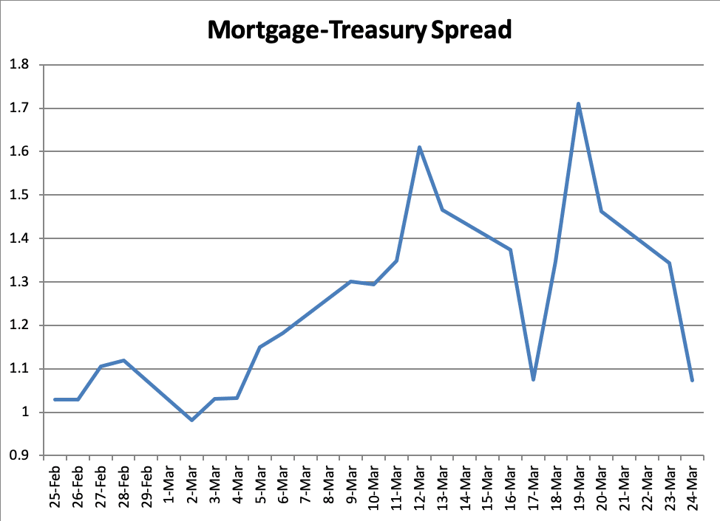

The spread between government-guaranteed mortgage backed securities and Treasuries, one of the safest assets, did contract, but only because the Federal Reserve was buying. There is a $15 trillion overhang of such securities which hedge funds as well as overseas investors, and the Fed has been playing whack-a-mole with the market for the past week, with wild swings in prices.

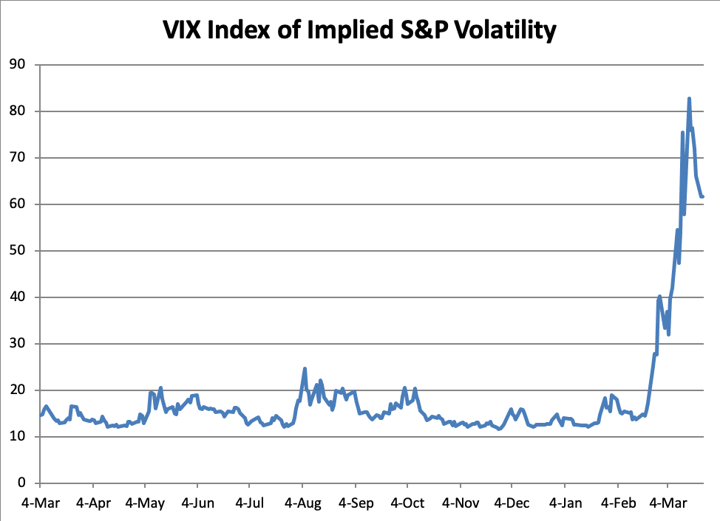

Another thing that didn’t rally was the cost of hedging against further market declines in the options market. The normalized cost of options of the S&P 500, the VIX index of implied volatility, was unchanged from Monday at extremely high levels.

One of the invariant rules of market behavior is that the cost of hedging falls when stocks rise, except for today, when the cost of hedging was unchanged despite an apparently world-beating rally. This is the biggest such discrepancy in the past 12 years, including the 2008 World Financial Crash. The close relationship between changes in the level of the S&P and the VIX would have predicted a fall in the VIX of about 15 percentage points, but it didn’t fall at all. The fact that it was unchanged shows that today’s bounce did nothing to reduce investor uncertainty.

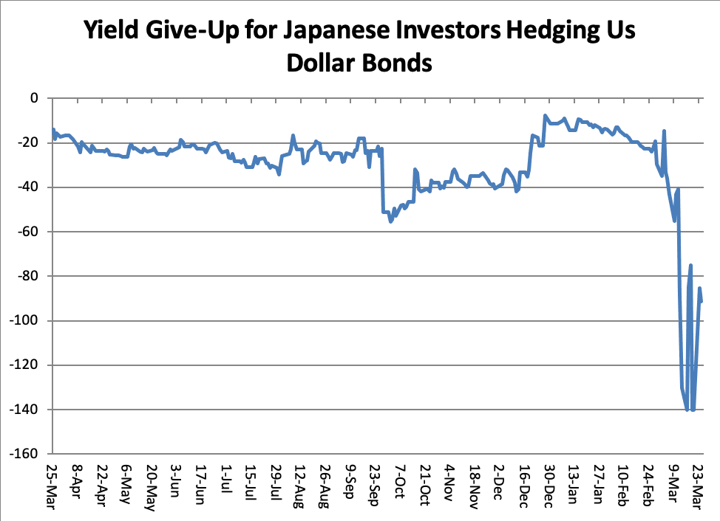

Perhaps the most important market parameter that failed to rally is the US dollar-Japanese yen cross-currency basis swap, the amount of yield that Japanese investors sacrifice to hedge US dollar coupon payments into Japanese yen. The collapse of the basis swap to levels that effectively prohibit the Japanese from buying and hedging US bonds probably is the most important cause of chaos in the market for high-quality US bonds.

As I explained in a March 13 analysis for Asia Times, this is a gauge of liquidity rationing among international banks. European and Japanese banks have borrowed about $12 trillion from US banks to fund hedges, and the rush for cash shut this market down. The Federal Reserve has pumped perhaps $100 billion in dollar liquidity into the market in the form of swap lines to foreign central banks, who in turn provide dollars for commercial banks. Compared to a $12 trillion volume of net dollar borrowing by foreign banks, the Fed’s swap lines probably are too small to make a lasting difference. Federal Reserve intervention, as the chart shows, hasn’t succeeded in restoring the cross-currency basis swap to normal levels.

Trillions of dollars of US securities held by foreigners are waiting to be sold, and it remains to be seen whether the Fed has the resources to engineer a soft landing.